Your Router Is Collecting Data. Here’s What to Know, and How to Protect Your Privacy

Your home’s Wi-Fi router is the central hub of your home network, which means that all of the traffic from all of the Wi-Fi devices under your roof passes through it on its way to the cloud. That’s a lot of data — enough so to make privacy a reasonable point of concern when you’re picking one out.

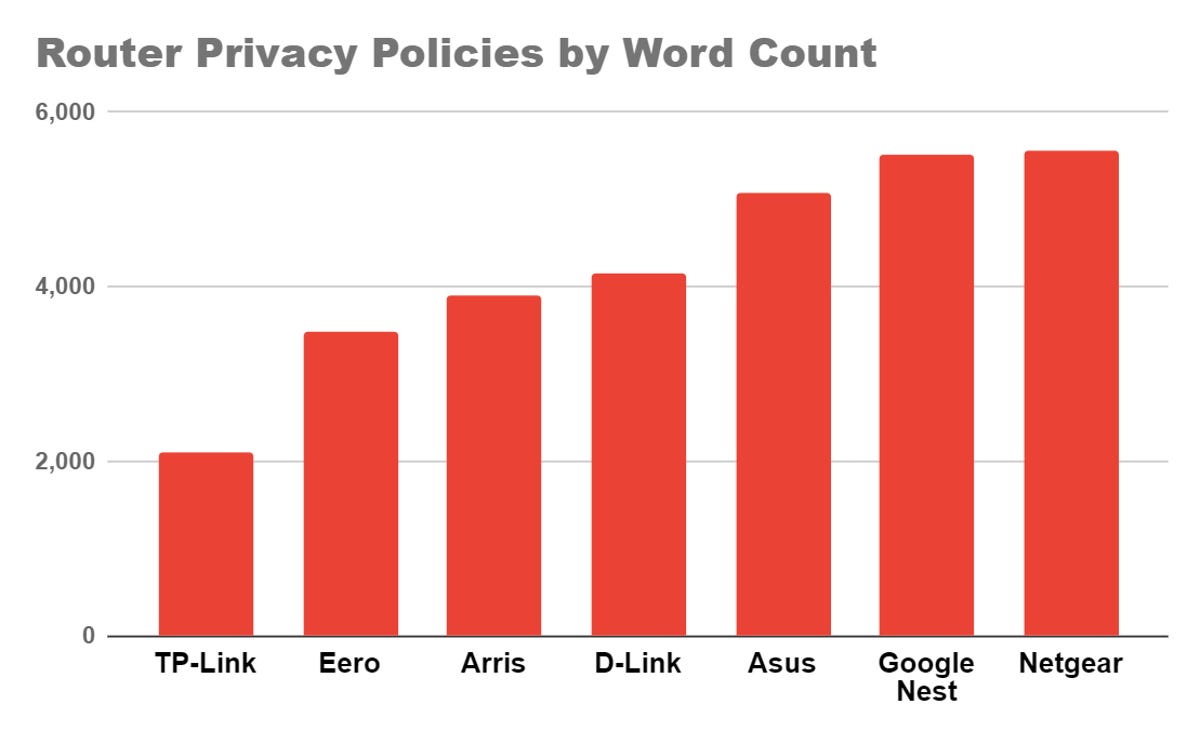

The problem is that it’s next to impossible for the average consumer to glean very much about the privacy practices of the companies that make and sell routers. Data-collection practices are complicated to begin with, and most privacy policies do a poor job of shedding light on them. Working up the will to read through the lengthy legal-speak that fills them is no small task for a single manufacturer, let alone several of them. Even if you make it that far, you’re likely to end up with more questions than answers.

Fortunately, I have a strong stomach for fine print, and after spending the last few years testing and reviewing routers here on CNET, most manufacturers tend to respond to my emails when I have questions. So, I set out to dig into the details of what these routers are doing with your data — here’s what I found.

The problem(s) with privacy policies

I combed through about 30,000 words of terms of use and other policy documents as I tried to find answers for this post — but privacy policies typically aren’t written with full transparency in mind.

“All a privacy policy can really do is tell you with some confidence that something bad is not going to happen,” said Bennett Cyphers, a staff technologist with the privacy-focused Electronic Frontier Foundation, “but it won’t tell you if something bad is going to happen.”

“Often, what you’ll see is language that says, ‘we collect X, Y and Z data, and we might share it with our business partners, and we may share it for any of these seven different reasons’, and all of them are very vague,” Cyphers continued. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that the company is doing the worst thing you could imagine, but it means that they have wiggle cover if they choose to do bad stuff with your data.”

He’s not wrong: Most of the privacy policies I reviewed for this post included plenty of the “wiggle cover” Cyphers described, with broad, vague language and relatively few actual specifics. Even worse, many of these policies are written to cover the entire company in question, including all of its products, services and websites, as well as the way it handles data from sales transactions and even job applications. That means that much of what’s written might not even be relevant to routers.

All of the router privacy policies mentioned in this post are thousands of words long, and much of what’s in them can be confusing or irrelevant to users.

Ry Crist/CNET

Then there’s the issue of length. Simply put, none of these privacy policies make for quick reading. Most of them are written in carefully worded legalese that’s crafted more to protect the company than to inform you, the consumer. A few manufacturers are starting to get a bit better about this, with overview sections designed to summarize the key points in plain English, but even then, specifics are typically sparse, meaning you’ll still need to dig deeper into the fine print to get the best understanding of what’s going on with your data. In cases where a company uses a third-party partner to offer additional services like threat detection or a virtual private network, you may need to read multiple privacy policies in order to follow your data to the fullest.

All of that made for a daunting task as I set out to read through everything, so I focused my attention on finding the answers to a few key questions for each manufacturer. All of the policies I read confirmed that the company in question collected personal data for the purpose of marketing, but I wanted to know which ones, if any, track user web activity, including websites visited while browsing. I also tried to determine if any manufacturers were sharing the personal data they collect with third parties outside of their control, and whether or not they were “selling” personal data as defined by the California Consumer Privacy Act.

Router manufacturer privacy practices

| Tracks Online Activity | Shares Personal Data with Outside Third Parties | Sells Personal Data | Allows Users to Opt Out of Data Collection | |

| Arris | No | No | Yes* | No |

| Asus | No | No | No | Yes |

| D-Link | Unclear | No | No | No |

| Eero | No | No | No | No |

| Google Nest | No | No | No | Yes |

| Netgear | No | No | No | No |

| TP-Link | No | No | No | No |

*CommScope, which manufactures Arris networking products, claims that it does not sell data collected from products, but rather, that some of its business operations including order fulfillment and data analytics may constitute a sale under California law. You can find more details on that in the “Is my data being sold?” section.

Is my router tracking the websites I visit?

Almost all of the web traffic in your home passes through your router, so maybe it’s difficult to imagine that it isn’t tracking the websites that you’re visiting as you browse. Every major manufacturer I looked into discloses that it collects some form of user data for the purpose of marketing — but almost none of the policies I read included any language that explicitly answered the question of whether or not a user should expect their web history to be logged or recorded.

The sole exception? Google.

Google’s privacy notice for Nest Wifi and Google Wifi devices was the only policy I found from any manufacturer that explicitly states that the products do not track the websites you visit.

Chris Monroe/CNET

“Importantly, the Google Wifi app, Wifi features of the Google Home app, and your Google Wifi and Nest Wifi devices do not track the websites you visit or collect the content of any traffic on your network,” Google’s support page for Nest Wifi privacy reads. “However, your Google Wifi and Nest Wifi devices do collect data such as Wi-Fi channel, signal strength, and device types that are relevant to optimize your Wi-Fi performance.”

I asked each of the six other companies I looked into for this post whether or not they tracked the websites their users visit. Though none of them indicate as much in their privacy policies, representatives for five of them — Eero, Asus, Netgear, TP-Link and CommScope (which makes and sells Arris Surfboard networking products) — told me that their products do not track the sites that users visit on the web.

“Eero does not track and does not have the capability to track customer internet browsing activity,” an Eero spokesperson shared.

“Asus routers do not track what the user is browsing nor do our routers include targeting or advertising cookies,” an Asus spokesperson said.

“Netgear routers do not track any user web activity or browsing history except in cases where a user opts in to a service and only to provide information to the user,” a Netgear spokesperson said, offering the examples of parental controls that allow you to see the sites your child has visited, or cybersecurity features that let you know what sites have been automatically blocked.

TP-Link also told CNET that it doesn’t collect user browsing history for marketing purposes, but the company muddies the waters with confusing and contradictory language in its privacy policies. Section 1.2 of the company’s main privacy policy says that browsing history is only collected when you use parental control features to monitor your child’s web usage — but a separate page for residents of California, where disclosure laws are more strict, says that browser history is collected using cookies, tags, pixels and other similar technologies, anonymized, and then shared internally within the TP-Link group for direct marketing purposes.

When I asked about that discrepancy, a TP-Link spokesperson explained that the cookies, tags and pixels mentioned in that California disclosure are referring to trackers used on TP-Link’s website, and not referring to anything its routers are doing.

“I will say our policy can be clearer,” the spokesperson said. “That’s something we’re kind of working on right now, internally.”

CommScope, too, says that its products don’t collect a user’s browsing history — though the company makes a distinction between retail products sold directly to consumers and the routers it provides via service partnerships with third-party partners, most notably internet service providers.

“Regarding our retail Surfboard products, CommScope has no access or visibility to an individual users’ web browsing history or the content of the network traffic flowing through these retail products,” a company spokesperson said.

Meanwhile, D-Link did not respond to multiple requests for clarification about its data collection practices, and it’s unclear whether or not the company’s products track any user browsing data. I’ll update this post if and when I hear back.

Ry Crist/CNET

Where is my data going?

Even if your router isn’t tracking the specific websites you visit, it’s still collecting data as you use it. Much of this is technical data about your network and the devices that use it that the manufacturer needs to keep things running smoothly and to detect potential threats or other issues. In most cases, your router will also collect personal data, location data, and other identifiers — and like I said, every company I looked into acknowledged that it uses data like that for marketing purposes in one way or another.

Using your data for marketing often means that your data is being shared with third parties. The danger is that a company might share it with a third party outside of its control, that would then be free to use and share your data however it likes.

“When data is used to target ads, it’s usually not just used by the company that’s collecting the data,” said Cyphers. “The company is going to share it with a number of advertising companies who might share it downstream with a number of other, vaguely ad-related companies. All of them are going to use that data to augment profiles they already have about you.”

With respect to routers, all of the companies I looked at acknowledged that they share user data with third parties for marketing purposes. The majority of these companies claim that these are in-house third parties bound by the company’s own policies, and all of the companies I reached out to said that they don’t share data with third parties for their own, independent purposes. Still, that’s a tall ask for privacy-conscious consumers.

CommScope notes that the way it handles and shares data used for performance analytics with its Arris Surfboard routers constitutes a sale of personal data under California law.

Ry Crist/CNET

Is my data being sold?

I also asked the companies I looked into for this post whether or not they sell data that could be used to personally identify a user, as defined by the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018. That law defines a “sale” broadly to include, “selling, renting, releasing, disclosing, disseminating, making available, transferring, or otherwise communicating orally, in writing, or by electronic or other means, a consumer’s personal information by the business to another business or a third party for monetary or other valuable consideration.”

Most of the companies indicate in their privacy policies that they do not sell personal data, but the CommScope privacy policy acknowledges that it shares information, including identifiers as well as internet and other network activity information, for purposes including marketing in a way that qualifies as a sale.

“Data used for some of our business operations like order fulfillment and performance analytics as well as the use of ‘cookies’ on our CommScope.com and Surfboard.com websites may constitute the ‘sale’ of ‘personal information’ under a conservative reading of the California law,” a CommScope representative says.

There’s some nuance to that “yes” on the question of whether or not the company sells data, especially since things like order fulfillments and cookies on CommScope’s website don’t directly relate to the use of CommScope home networking hardware. Still, it’s noteworthy that the company acknowledges that some of its practices may constitute a sale under California law when the majority of the manufacturers I looked at did not.

“We can say that we do not sell data collected from the modems nor is that data used for marketing purposes by CommScope,” the company added. “But where modems are ordered from us directly or where we provide customer support, that information is ‘sold’ (our read of the California law) only as part of filling that order and providing those services.

“Where we supply modems/gateways to service providers, they control their own privacy policy controls,” the company added.

Users in California have the right to tell CommScope not to sell their data on this website, but CommScope says that it “reserves the right to take a different approach” when responding to requests from users who live elsewhere.

Meanwhile, TP-Link tells CNET that it does not sell user personal data and that none of the data collected by its routers are used for marketing at all. Still, the company’s privacy policy appears to create wiggle room on the topic: “We will not sell your personal information unless you give us permission. However, California law defines ‘sale’ broadly in such a way that the term sale may include using targeted advertising on the Products or Services, or how third party services are used on our Products and Services.”

Motorola router users can find a clear option for opting out of data collection in the settings section of the Motosync app used to manage their device.

Screenshot by Ry Crist/CNET

Can I opt out of data collection altogether?

With some manufacturers, the answer is yes. With others, you can request to view or delete the data that’s been collected about you. Regardless of the specifics, some manufacturers do a better job than others of presenting clear, helpful options for managing your privacy.

The best approach is to give users an easy-to-locate option for submitting an opt-out request. Minim, the company that manages Motorola’s home networking software, is a good example. Head to the settings section of the company’s Motosync app for routers like the Motorola MH7603, and you’ll find a clear option for opting out of data collection altogether. Asus offers a similar option, telling CNET, “users can opt out or withdraw consent for data collection in our router setting interface at any time by clicking the “withdraw” button.”

Unfortunately, that approach is more exception than norm. The majority of manufacturers I looked into make no mention of opting out of data collection within their respective apps or web platforms, choosing instead to process opt-out and deletion requests via email or web form. Usually, you’ll find those links and addresses in the company’s privacy policy — typically buried towards the end, where few are likely to find them.

That’s the case with Netgear. Pursuant to Apple’s policies, the company discloses its data collection during setup on iOS devices, complete with options for opting out, but there’s no way to opt out in the app after that. Android users, meanwhile, get no option to opt out at all.

“From the Android app (or iOS), a user can go to About > Privacy Policy and click on the web form link in Section 13 to delete their personal data,” a Netgear spokesperson said. “We will look into making this option less hidden in the future.”

Other manufacturers, including D-Link and TP-Link, don’t offer a direct means of opting out of data collection, but instead, instruct privacy-conscious users on how to opt out of targeted advertising via Google, Facebook or Amazon, or to install blanket Do Not Track cookies offered by self-regulatory marketing industry groups like the Digital Advertising Alliance and the Network Advertising Alliance. That’s better than nothing, but a direct means of opting out would make for a better approach — especially since some companies might not make use of Do Not Track signals like those.

“At this time, TP-Link does not honor Do Not Track signals,” the company’s privacy policy states.

Sections 8b and 8c of Eero’s privacy policy make it clear that the only way to opt out of data collection is not to use Eero devices at all. Requesting that Eero delete the personal data it’s gathered about you will render the devices inoperable, and Eero may still keep a backup of your data afterwards.

Screenshot by Ry Crist/CNET

This brings us to Eero. The company does not offer an option for opting out of data collection, and instead tells users that the only way to stop its devices from gathering data is to not use them.

“You can stop all collection of information by the Application(s) by uninstalling the Application(s) and by unplugging all of the Eero Devices,” the Eero privacy policy notes.

You can ask Eero to delete your personal data from its records by emailing [email protected], but the company claims that there’s no way for it to delete its collected data without severing a user’s connection to Eero’s servers and rendering devices inoperable.

The privacy policy also notes that the company “may be permitted or required to keep such information and not delete it,” so there’s no guarantee that your deletion request will actually be honored. Even if Eero does agree to delete your data, that doesn’t mean that the company won’t keep a backup.

“When we delete any information, it will be deleted from the active database, but may remain in our backups,” Eero’s policy reads.

The takeaway

Data collection is all-too-common in today’s consumer tech, including concerns with smartphone apps, social media, phone carriers, web browsers and more. I’d rank my concerns with routers beneath those — but your home networking privacy is still something worth paying attention to.

From my perspective, opting out of data collection wherever you can is typically a good idea, even if the collection itself seems harmless. There’s simply no good way to know for certain where your data will end up or what it will be used for, and privacy policies will only tell you so much about what data is actually being collected. To that end, I’ve listed your options for opting out with each of the manufacturers covered in this post below. And, as I continue to test and review networking hardware, I’ll keep this post up to date.

Asus

You can withdraw consent for data collection by heading to the settings section of the Asus web interface, clicking the Privacy tab, and then clicking “Withdraw.” You can reach that web interface by entering your router’s IP address into your browser’s URL bar while connected to its network, or by tapping the options icon in the top left corner of the Asus Router app and then selecting “Visit Web GUI.”

CommScope (Arris)

If you live in California, you can tell CommScope not to sell your data by filling out a form on this website, but the company won’t guarantee that it will honor requests if you live elsewhere. There isn’t a direct option for opting out of data collection in any of the apps used to set up and manage CommScope products, but the company notes that you can unsubscribe from promotional emails at any time.

D-Link

D-Link does not offer a direct option for opting out of data collection, but instead, directs you to opt out of interest-based advertising from participating companies by using Do Not Track cookies provided by the Network Advertising Initiative, a self-regulatory marketing industry group.

Eero

Eero has no opt out setting for data collection, as Eero claims that its devices are unable to function without sending device data to Eero’s servers.

Google Nest

You can manage your Google Wifi or Nest Wifi privacy settings and opt out of certain data collection practices by opening the Google Home app and tapping Wi-Fi > Settings > Privacy Settings.

Netgear

Netgear doesn’t offer an option for completely opting out of data collection, but you can fill out a form on this website to download and view any data that Netgear has collected or request that Netgear delete that data.

TP-Link

TP-Link doesn’t offer a direct option for opting out of data collection, but it does share instructions for opting out of interest-based advertising via Facebook, Google and Amazon on its website. The site also offers information about Do Not Track cookies available from the Digital Advertising Alliance and the Network Advertising Initiative, which are self-regulatory marketing industry groups.

For all the latest world News Click Here