When Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Rabindranath Tagore argued over religious rights – Times of India

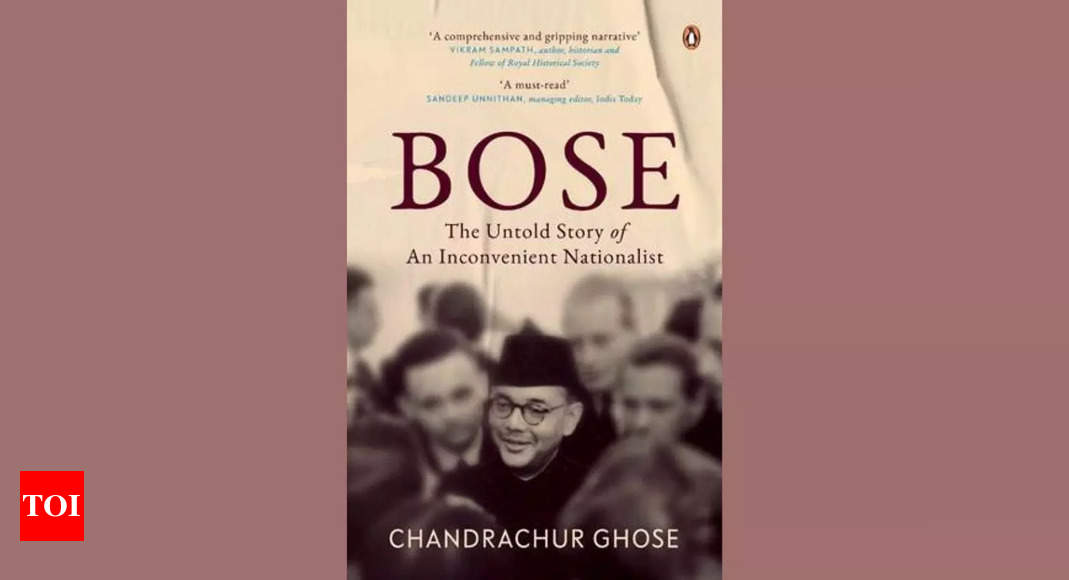

Shedding more light on the unknown and controversial life of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, author-researcher-commentator Chandrachur Ghose has written a new book titled ‘Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist’ which was published on February 21, 2022.

Here’s an exclusive excerpt from the book ‘Bose: The Untold Story of an Inconvenient Nationalist’ by Chandrachur Ghose, published with permission from Penguin India.

Another controversy that pitched Subhas against Rabindranath erupted in early 1928, around organizing Saraswati Puja in a hostel of the City College in Calcutta. The college being an institution of the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, which did not believe in idol worship, the authorities allowed the students to organize the puja outside the hostel campus but not within. The students, however, disregarded the warning by the college authorities and held the puja inside the campus of the Ram Mohan Roy Hostel, as a consequence of which disciplinary action was taken against about six of them, the hostel was shut down and an early summer vacation declared. A number of students transferred to other colleges. In the ensuing confrontation between the students and the authorities, Subhas came out in support of the students.

Rabindranath expressed his views in an article in The Modern Review. Had the students not insisted on organizing the puja in a Brahmo hostel, the ‘religion of the Hindus’ would not have ‘in any way been hurt’, and ‘it is Religion which is hurt by needlessly hurting the feelings of any religious community’. He had taken up the pen, Rabindranath wrote, because the incident was not a matter of local clash, but involved a higher principle. In spite of its rules against image worship, the college had been accepted by students of various religions. ‘If now some group of men should, by propaganda of cajolery or intimidation, succeed in putting it into difficulties, that would be sowing the seed of rankling thorns in the mind of one of the communities of our countrymen’, he argued. The logical question that followed was if such behaviour would ‘amount to a cultivation of the spirit of Swaraj which is to give legitimate freedom of self-expression to all natural differences in the communities that come under it’.

Rabindranath presented several analogies to explain his arguments. ‘Would it be right to restrain Mahomedan students,’ he asked, ‘if in accordance with their own religion they wanted to sacrifice a cow in the grounds of a hostel occupied by them but managed by the Hindus?’ If cow slaughter is a sin for the Hindus, ‘the Musalmans have proclaimed in their history, in letters of blood, that it is a sin beyond all other sins to worship any created thing as God’. Rabindranath dared those ‘who are so loud in their assertion that their religion demands the performance of their own sectarian worship even on ground occupied by a different sect,’ to demonstrate their belief ‘on Musalman and Christian territory’. Thereafter, he went on to praise the Christian rulers of India:

Those who are the rulers of India are Christians. As to power, they have more than is possessed by any other religion in India. As for contempt and hatred, they are wanting in neither for the Hindu rites and practices And yet they have not taken to thrusting the Christian form of worship into our homes, our schools, our temples. Had they done so, they would doubtless have had showers of benedictions on such crusade from the pious pundits of their own church. Nevertheless, they have preferred to do without such benediction, rather than propagate their religion by force in the fields sacred to non-Christian religions.

C.F. Andrews joined in the chorus, asserting that ‘the students’ attempt to coerce the college authorities into allowing public image worship to be performed in the Ram Mohun Roy Hostel is contrary to the spirit of mutual toleration and forbearance which was introduced by the Unity Conference and confirmed by the Madras Congress Resolution, in December 1927’.

Announcing his support for the Hindu students at a students’ meeting in the Albert Hall on 1 March 1928, Subhas claimed that the resolution of the dispute was simple, although efforts were afoot to make a mountain out of a molehill. The Hindus were an extremely tolerant community and he was unwilling to impose his own religious beliefs on anyone else. At the same time, it was beyond his comprehension ‘how the enlightened and progressive Brahmo leaders could stoop so low to force their belief on Hindu students’.208 On 18 May, he issued another statement urging the college authorities to allow religious freedom to students of both the communities. ‘The relationship between Brahmo Samaj and the Hindu community is not the same as those between Hindus and Muslims or Hindus and Christians’, he emphasized. For Subhas, the Brahmos were part of the Hindu community: it had become a tradition for the Brahmos to introduce themselves as Brahmo-Hindus, and many leaders of their community had been playing an active role in the Hindu Mahasabha. He appealed to the authorities for a little more tact and less vengefulness in dealing with the students.

After the publication of Rabindranath’s essay in The Modern Review, Subhas responded to the points raised by the poet at another meeting in the Albert Hall on 19 June:

I am very sorry to see Rabi babu and Mr Andrews get involved in this matter… When sometime back we had requested Rabindranath to join our political movement, he had refused. I fail to understand why then he has been summoned now and why he has agreed to join the issue. He has raised the question of Hindu–Muslim relationship in his essay. At the risk of being sounding arrogant I say this comparison is wrong. The City College affair is really a domestic affair like a conflict between Shaktas and Vaishnavas. He has also asked why organising the Puja is being forced now when for so many years there had been no such demand. Should we then continue to remain an enslaved nation just because we have remained so for a hundred and fifty years?

Whenever religions have been in conflict in our country, a synthesis has been found. Images of Hari–Hara, Kali–Shiva, Hara–Gauri and Kali–Krishna, etc., are examples of that synthesis… We establish the divine spirit within idols and worship the infinite within the finite. There is no need for any conflict. Worship of idols by Hindus does not demean the religious beliefs of the Brahmos.

The question of religious tolerance has also come up. Toleration of others’ beliefs does not mean giving up one’s own belief. Toleration is true when every individual is allowed to observe his own religion. In my opinion, the Brahmo leaders have shown greater intolerance by not allowing the students to do the puja.

Being a civic festival, Saraswati Puja has a societal value too… It is not right to deprive the society from the pure and unmixed joy on the occasion of the puja. It also has a value from the perspective of art and culture. If symbols are necessary in the world of art, what can be the objection to symbols in religion?

There is no substance in the allegation that disrespect has been shown to Raja Ram Mohan Roy by organising the puja. Certainly, he had his differences with idol worship, but it was he who aggressively defended the Hindus against the Christian missionaries when they campaigned against idol worship.

The Bengali satire magazine, Shanibarer Chithi, led by its editor Sajanikanta Das, too defended the college authorities, the primary target of its satire being ‘Subu Bose’. Sajanikanta was convinced that the students were in the wrong and the dispute became protracted only because of Subhas’s involvement. Although his Brahmo colleagues in the magazine were hesitant to hit out in strong language, Sajanikanta claimed that being a Hindu himself, he was not restricted by such hesitation in attacking the Hindu religionists. He wrote satirical articles and poems attacking Subhas in quite a tasteless manner, calling him ‘Khoka Bhagawan’ (baby God), ridiculing his illness in Mandalay Jail and his bachelor status. Mocking Subhas’s religiosity, Sajanikanta wrote that it had become a fashion to grow a tuft of hair (like Brahmins) in Cambridge. Sajanikanta admitted later in his memoirs that Subhas’s role in the City College affair angered him so much that the magazine continued to lampoon him for a long time for all his other activities, especially for his role as the General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the volunteer corps during the Calcutta Congress held in December that year. So intense was his dislike for Subhas that Sajanikanta abstained from participating in the Calcutta Congress.

A repentant Sajanikanta apologized in his memoirs:

Later Gok Subhas [named so for his role of GOC] turned the table on us by truly becoming Netaji Subhaschandra, rejecting our satire and making it an object of ridicule. Today all of us are proud of him and our unadulterated respect for him has put a cover on our earlier shame.

READ MORE: When the popularity of the Scindias ‘displeased’ Nehru

8 books to understand Russia-Ukraine conflict

For all the latest lifestyle News Click Here