Understanding ethanol blending

How is ethanol extracted? What are the environmental concerns with respect to this process?

How is ethanol extracted? What are the environmental concerns with respect to this process?

The story so far: Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India has achieved its target of blending 10% sugarcane-extracted ethanol in petrol, ahead of schedule. Addressing the nation from the Red Fort on the 76th Independence Day, he rooted for energy independence stating that, “we need to be Aatmanirbhar (self-sufficient) in our energy sector”. India is one of the world’s biggest oil importing nations.

What is ethanol blending?

Blending ethanol with petrol to burn less fossil fuel while running vehicles is called ethanol blending. Ethanol is an agricultural by-product which is mainly obtained from the processing of sugar from sugarcane, but also from other sources such as rice husk or maize. Currently, 10% of the petrol that powers your vehicle is ethanol. Though we have had an E10 — or 10% ethanol as policy for a while, it is only this year that we have achieved that proportion. India’s aim is to increase this ratio to 20% originally by 2030 but in 2021, when NITI Aayog put out the ethanol roadmap, that deadline was advanced to 2025.

Ethanol blending will help bring down our share of oil imports (almost 85%) on which we spend a considerable amount of precious foreign exchange. Secondly, more ethanol output would help increase farmers’ incomes.

The NITI Aayog report of June 2021 says, “India’s net import of petroleum was 185 million tonnes at a cost of $55 billion in 2020-21,” and that a successful ethanol blending programme can save the country $4 billion per annum.

What are first generation and second generation ethanols?

With an aim to augment ethanol supplies, the government has allowed procurement of ethanol produced from other sources besides molasses — which is first generation ethanol or 1G. Other than molasses, ethanol can be extracted from materials such as rice straw, wheat straw, corn cobs, corn stover, bagasse, bamboo and woody biomass, which are second generation ethanol sources or 2G.

While inaugurating the Indian Oil Corporation’s (IOC) 2G ethanol plant last week, Mr. Modi referred to not only the prospect of higher farmer income but also dwelt upon the advantages of farmers selling the residual stubble — left behind after rice is harvested — to help make biofuels. This means lesser stubble burning and therefore, lesser air pollution.

How have other countries fared?

Though the U.S., China, Canada and Brazil all have ethanol blending programmes, as a developing country, Brazil stands out. It had legislated that the ethanol content in petrol should be in the 18-27.5% range, and it finally touched the 27% target in 2021.

How does it impact the auto industry?

At the time of the NITI Aayog report in June last year, the industry had committed to the government to make all vehicles E20 material compliant by 2023. This meant that the petrol points, plastics, rubber, steel and other components in vehicles would need to be compliant to hold/store fuel that is 20% ethanol. Without such a change, rusting is an obvious impediment.

Rajesh Menon, director-general of the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers says that the industry has committed to becoming E20 engine compliant by 2025, which means that engines would need to be tweaked so as to process petrol which has been blended with 20% ethanol.

Are there other alternatives?

Sources in the auto industry state that they prefer the use of biofuels as the next step, compared to other options such as electric vehicles (EV), hydrogen power and compressed natural gas. This is mainly because biofuels demand the least incremental investment for manufacturers.

Even though the industry is recovering from the economic losses bought on by the pandemic, it is bound to make some change to comply with India’s promise for net-zero emissions by 2070.

What are the challenges before the industry when it comes to 20% ethanol blended fuel?

The Niti Aayog report points out that the challenges before the industry are: “optimisation of engine for higher ethanol blends and the conduct of durability studies on engines and field trials before introducing E20 compliant vehicles.”

Sources say that the auto industry is in talks with the government to plan this transition. There are multiple issues at stake for this endeavour. Storage is going to be the main concern, for if E10 supply has to continue in tandem with E20 supply, storage would have to be separate which then raises costs.

What have been the objections against this transition?

Ethanol burns completely emitting nil carbon dioxide. By using the left-over residue from rice harvests to make ethanol, stubble burning will also reduce. The 2G ethanol project inaugurated last week will reduce greenhouse gases equivalent to about three lakh tonnes of CO2 emissions per annum, which is the same as replacing almost 63,000 cars annually on our roads. However, it does not reduce the emission of another key pollutant — nitrous oxide.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) in a report in March talks about the inefficient land use in ethanol production. The report’s author Charles Worringham said that we can use land far more efficiently by generating renewable power for EV batteries. For example, to match the annual travel distance of EVs recharged from one hectare generating solar energy, 187 hectares of maize-derived ethanol are required, even when one accounts for the losses from electricity transmission, battery charging and grid storage.

The water needed to grow crops for ethanol is another debating point. An explainer in The Hindu in May states that for India, sugarcane is the cheapest source of ethanol. On average, a tonne of sugarcane can produce 100 kg of sugar and 70 litres of ethanol — meaning, a litre of ethanol from sugar requires 2,860 litres of water.

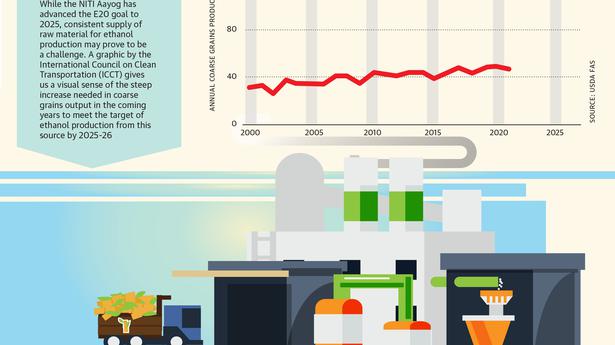

There has been, therefore, a move toward waste-based extraction, such as through coarse grains. But supply may still be a problem, though the Niti Aayog report sounds sanguine on this count — “the roadmap estimates ethanol production from domestic grains will increase a whopping fourfold by 2025.” The abnormally wet monsoon seasons may have helped in recent years to raise grain output, but in its August 2021 analysis The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) is sceptical that those production increases can be sustained.

Mr. Worringham states that sugar cane would likely continue to be the primary source for ethanol even with the 12 planned farm waste — or 2G ethanol — distilleries. The first, inaugurated last week, has a capacity to produce 100 kilo litres a day, or 3.65 crore litres a year. The 2021 Ethanol Roadmap forecasts that an additional 800 crore litres of ethanol is needed annually to meet the target. He points out that “assuming the other 11 planned farm waste distilleries have similar rates of production, their combined input would barely produce 5% of the additional annual ethanol requirement.”

What about food security concerns?

Mr. Worringham also flags the impact on crop output meant for food and fodder. “There are already indications that more sugarcane is being grown and that the Government of India encouraged more corn production at the India Maize Summit in May, with its use for ethanol production cited as a reason for this push. Sugar and cane production that end up in the petrol tank cannot also appear on the dinner plate, in animal fodder, be stored in warehouses, or be exported. As was evident in India’s wheat harvest earlier this year, climate change-induced heatwaves are a worrying factor and can lead to lower-than-expected harvests with little notice,” he says.

Global corn, or maize, production is down, and this adds an incentive for India to try and export more. In France, the corn harvest has dipped 19%, and reductions in forecast production have been seen for at least seven other countries in Europe. U.S. production expectations have also been revised slightly downward.

“Given the uncertainty about future production, India may not find it easy to simultaneously strengthen domestic food supply systems, set aside adequate stocks for lean years, maintain an export market for grains, and divert grain to ethanol at the expected rate in coming years, and this is an issue that warrants continued monitoring,” he warns.

THE GIST

Blending ethanol with petrol to burn less fossil fuel while running vehicles is called ethanol blending. Ethanol is an agricultural by-product. It’s mainly obtained in the processing of sugar from sugarcane, but also from other sources such as rice husk or maize.

The auto industry has committed to make all vehicles E20 (20% ethanol in petrol) material compliant by 2023. This means that the petrol points, plastics, rubber, steel and other components in vehicles would need to be compliant to hold/store fuel that is 20% ethanol.

While ethanol blending can reduce CO2 emissions, inefficient land and water use for ethanol extraction as well as food security concerns still remain.

For all the latest business News Click Here