Uber deliberately dodged authorities, ignored rules in early years, leaked documents show | CBC News

Revenu Quebec agents had been investigating Uber for weeks, including making undercover visits to the company’s Montreal offices and following its Quebec general manager to work one day. They suspected the ride-hailing service was improperly declaring that it owed no provincial sales tax and helping some drivers dodge that tax and the federal GST.

On May 13, 2015, they got a search warrant, and the next day they raided the company’s premises. But at 10:40 a.m., at two Uber offices in Montreal, investigators noticed company laptops, smartphones and tablets suddenly all restarted at exactly the same time.

Worried that data on the devices might be being manipulated from afar, the agents powered them down. They seized 14 computers, 74 phones and some documents, according to court records obtained by CBC/Radio-Canada.

Uber’s Quebec general manager at the time, Jean-Nicolas Guillemette, told the investigators that he had contacted engineers at the company’s headquarters in San Francisco who had encrypted all the data remotely.

What happened in Montreal was far from an isolated incident, but a tactic Uber used to try to thwart authorities in cities where it was trying to establish its business, according to documents found in the Uber Files, a large new leak of internal records from the gig-economy company.

The leaked records show how the company that launched itself as a luxury ride service in San Francisco in 2010 tried to surmount legal and political obstacles through a complex choreography of lobbying, cultivating influential allies, dodging authorities and ignoring the rules when they appeared inconvenient.

The leaked files contain 124,000 records, including 83,000 emails, iMessages and Whatsapp exchanges between Uber’s most senior executives as well as memos, presentations and invoices. The records, spanning from 2013 to 2017, shed light on a period when Uber was aggressively expanding and operating illegally by ignoring taxi regulations in many cities around the world, including in Canada.

The files were leaked to The Guardian and shared with the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a non-profit newsroom and network of journalists whose media partners include CBC/Radio-Canada, the Toronto Star, the Washington Post, the BBC and Le Monde.

In a statement to the ICIJ, Jill Hazelbaker, a spokeswoman for Uber, acknowledged “mistakes” and “missteps” that culminated five years ago in “one of the most infamous reckonings in the history of corporate America,” but that the company had changed its practices since 2017.

Thwarting authorities

The leaked files reveal that a “kill switch,” as it was referred to internally, and an encryption software were also deployed in France, the Netherlands, Hungary, Romania and India, as government authorities raided company offices to enforce tax, transportation and other laws.

The “kill switch” would remotely cut access to the company servers located in San Francisco and prevent government authorities from getting company files while local staff would still appear to be collaborating with investigators.

According to a 2015 leaked email from a legal director for Uber in western Europe, the company was particularly concerned that authorities could get access to their list of drivers, making it “much easier for the taxman, regulators and police to terrify our supply” and enforce against it. “If we hand over the driver list, our goose may be cooked,” he added.

In one of the first such uses of the kill switch that shows up in the leak, when France’s competition and consumer agency raided the company’s Paris offices in November 2014, Uber’s European legal director at the time sent out an email titled “Kill Paris access now” at 3:14 p.m. local time. Thirteen minutes later, an engineering manager wrote back: “Done now.”

During a July 2015 raid by the French tax agency, Mark MacGann, the top Uber lobbyist in Europe, advised Thibauld Simphal, then head of Uber France, that employees play dumb when the kill switch is activated, according to leaked text messages.

“Try a few laptops, appear confused when you cannot get access, say that IT team is in [San Francisco] and fast asleep.”

The French manager responded: “Oh yeah we’ve used that playbook so many times by now the most difficult part is continuing to act surprised!”

MacGann told the Guardian he was just following orders. “On every occasion where I was personally involved in ‘kill switch’ activities, I was acting on the express orders from my management in San Francisco,” he said.

Simphal, now Uber global head of sustainability, said all his interactions with public authorities were conducted in good faith.

During an April 2015 raid on its Amsterdam offices, Uber’s manager for Western Europe emailed a company engineer: “Kill switch in [Amsterdam] asap please.”

Uber’s co-founder and then-CEO, Travis Kalanick, was looped into the email chain. Seven minutes later, he wrote: “Please hit the kill switch ASAP…. Access must be shut down in [Amsterdam].”

In a statement sent to ICIJ, a spokesperson for Kalanick said that the former CEO never authorized any actions or programs that would obstruct justice in any country.

He said Uber, like other businesses operating overseas, used tools to protect intellectual property and the privacy of its customers, and ensure due process rights in the event of an extrajudicial raid.

Kalanick’s spokesperson also said that the protocols do not delete any data and that all decisions about their use were vetted and approved by Uber’s legal and regulatory departments.

After the Montreal raid, Uber went to court to dispute the validity of the search warrants obtained by Revenu Québec.

A Quebec Superior Court judge ruled that the warrants were valid. He also mentioned that the remote shutdown and encryption of electronic devices “bears all the hallmarks of an attempt to obstruct justice” and that a judge could reasonably conclude that the company was seeking to hide evidence of illegal conduct from tax authorities.

It’s unclear what happened next with the investigation. A spokesperson for Revenu Quebec told CBC/Radio-Canada that the agency can’t comment on current or past investigations.

Uber eventually reached an agreement with Revenu Québec under which the company would collect the GST and QST on behalf of its drivers and remit the amounts to tax authorities.

Uber today trades as a public company worth $42 billion US — about the same as CIBC.

It says it operates in more than 10,000 cities and more than 70 countries. Its name has become a byword for ride-hailing apps in the many markets where it dominates, and it has branched into food delivery.

But at a bird’s eye level, the leaked records underscore that there was nothing inevitable about the company’s meteoric rise since its launch in San Francisco in 2010.

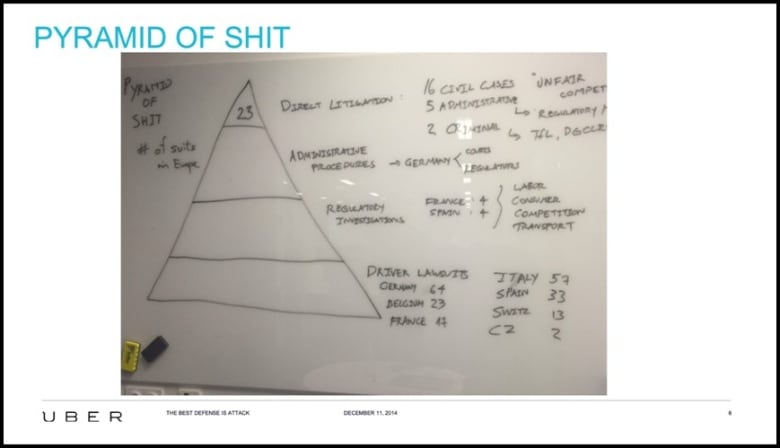

Uber’s deliberate strategy to establish itself would bring a lot of headaches, too. In a 2014 leaked presentation, the company characterized these issues as “the pyramid of shit,” formed by layers of direct litigation, administrative procedures, regulatory investigations and driver lawsuits.

Uber sought political allies to help it get around those hurdles and to keep pushing forward.

‘Backchannel route around Montreal’

When the UberX service launched in Montreal in 2014, Mayor Denis Coderre immediately publicly pronounced that “of course it’s illegal.”

Behind the scenes, Uber’s head of policy development sent an internal email saying: “This was fully anticipated and known but we’re working with the province and Quebec City as a back channel route around Montreal.”

When Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union, called for the Ontario government to intervene after UberX launched in Ottawa in October 2014, the same policy manager wrote: “We have met with and continue to meet with relevant provincial cabinet ministers to head off this issue.… We are meeting relevant provincial ministers across provinces in Canada.”

The next month, the City of Toronto decided to pursue an injunction against Uber for allegedly violating its taxi and limousine regulations.

The same day, mayor-elect John Tory issued a media release criticizing the city’s decision, saying: “Uber is a technology whose time has come, and which is here to stay.”

A leaked internal memo suggests that Uber’s policy team had “worked to secure [the] extremely positive response” from Tory.

Tory’s office didn’t respond to our questions.

On Oct. 4, 2014, John Baird, the federal minister of foreign affairs in Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s cabinet, complained on Twitter and Facebook of having waited 75 minutes for a cab in Ottawa. He publicly called on the city to allow Uber, which had started operating illegally in the capital.

A few days later, Uber’s policy team claimed to have “secured the foreign minister of Canada as a public endorser,” according to a leaked internal memo.

Baird’s spokesperson, Michael Ceci, said the former minister “has no recollection of Uber Canada staff contacting him.”

Uber also sought to influence elected officials and public opinion in Alberta.

In Edmonton, when UberX launched in December 2014, an internal memo sent to policy and communications staff noted: “Policy secured the popular former three-term mayor Bill Smith as our Rider Zero, a favourable op-ed in the Edmonton Journal by well-known Edmonton businessman Chris LaBossiere and friend of the current mayor, favourable tweets from Uber-supportive Edmonton city councillor Michael Walters and met with the deputy chief of staff to the mayor (second formal meeting to date) where it was confirmed that the mayor ‘is there’ with respect to ridesharing.”

Earlier that fall, another pro-Uber op-ed appeared in the Journal signed by David MacLean, who was then vice-president of Alberta Enterprise Group, a business lobby organization. An internal Uber email a week later suggests the company’s policy and communications team had “worked with” the organization on the piece.

Michael Walters, Chris Labossiere and David MacLean did not respond to request for comments from CBC/Radio-Canada.

When some Calgary city councillors pushed for a regulatory framework for ride-hailing services like Uber, the company launched its service there before new rules were adopted.

“Anticipating that the framework will make it hard for us to operate, we are planning to launch this Thursday,” an internal memo says.

A spokesperson for Uber Canada told CBC/Radio-Canada that in the early years, Uber met with elected officials “to brief them on the technology” and whenever someone expressed support for regulating the industry, it was noted.

Katie Wells, a postdoctoral researcher at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who has published papers about Uber, said much of the company’s behaviour can be understood as a product of a libertarian world view preferring small government with power concentrated in the hands of corporations calling many of the shots.

“They think they’re better than the state,” Wells said. “What they’ve done through all this lobbying work is they try to eviscerate the state — they try to evade it, they try to lessen it, they try to say: ‘Don’t worry about it, we’ll take care of that.'”

‘Violence guarantee success’

Many cities tried to shut Uber down by seeking injunctions, impounding vehicles and issuing fines to drivers.

In an internal email from 2014, Uber’s head of global communications at the time, Nairi Hourdajian, wrote “sometimes we have problems because, well, we’re just f–king illegal.”

When approached by ICIJ, Hourdajian declined to comment.

The taxi industry was outraged and staged protests in many cities, including Montreal, where some taxi drivers disrupted traffic at the Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport and pelted Uber drivers with eggs and snowballs.

In 2015, a protest in Paris turned violent, with vehicles set on fire and rocks thrown at Uber drivers.

As Paris taxi drivers staged another protest in January 2016, Uber’s then-CEO, Kalanick, wrote in a group text message that the risk of violence against its drivers should not be a deterrent: “I think it’s worth it.. Violence guarantee success,” and added “these guys must be resisted, no?”

“I believe that particular instruction from Travis was dangerous and selfish,” a former Uber executive told The Guardian. “He was not the guy on the street who was being threatened, who was being attacked.”

During the 2016 protests, a Paris lawyer acting on behalf of Uber sent an email asking to set up a meeting with the French prime minister, referring to the “tense context” of “violent action” by taxi drivers.

Kalanick’s spokesperson said he never suggested that Uber should take advantage of violence at the expense of driver safety.

Kalanick’s lawyers denied he exploited violence by taxi drivers to try to obtain regulatory changes beneficial to Uber.

WATCH | Taxi drivers protest against Uber in France in 2015:

Taxi drivers set fires, smash car windows and snarl traffic in Paris in protest against the ride-sharing service

Kanalick resigned as CEO in 2017 amid scandals of sexual harassment, racial discrimination and bullying within the company that had not been addressed under his watch.

Hazelbaker, a spokeswoman for Uber, told ICIJ that Uber completely changed how it operates in 2017 after facing high-profile lawsuits and government investigations that led to the ouster of Kalanick and other senior executives.

“We have not and will not make excuses for past behaviour that is clearly not in line with our present values,” she said, adding that the “kill switch” has not been used to thwart regulatory action since 2017 and such software “should never have been used” that way.

Powerful allies

In France, Uber was not only facing angry cab drivers but also a hostile government that was not very welcoming of Uber’s model and law-skirting attitude.

But the ride-hailing giant had an ace in its pocket.

On Oct. 1, 2014, a new law came into force imposing longer training for Uber drivers and banning Uber Pop, a popular service that allowed drivers with smaller cars to offer ride-hailing services.

The same day, top Uber leaders, including CEO Kalanick, held a confidential meeting with Emmanuel Macron, France’s minister of economy and industry at the time.

Coming out of the meeting, the Uber leaders were ecstatic. “In a word: spectacular […] a lot of work to come but, but we’ll dance soon,” MacGann, Uber’s top lobbyist in Europe, wrote in an internal email to colleagues. “Wicked meeting with Macron this morning. France loves us after all.”

When violent protests hit Marseilles in October 2015, regional authorities banned Uber drivers from operating in the city’s downtown core, around train stations and the airport. MacGann reached out by text message to Macron.

“Could you ask your cabinet to help us understand what is happening?”

Macron answered: “I will look into this personally. Give me all the facts and we will decide by this evening. Stay calm at this point, I trust you […] let’s stay in touch.”

That evening, the head of local national police began to reverse course, promising to clarify the order. Twelve days later, authorities issued a new order saying that the ban applied to unlicensed and unregulated Uber drivers in the jurisdiction. Authorities denied receiving any pressure from Macron’s ministry.

Internally, Uber took credit for the reversal. “Ban reversed after intense pressure from Uber,” said a leaked email.

In response to ICIJ’s questions, Macron’s office said the French services sector was in upheaval at the time because of the rise of platforms like Uber, which faced administrative hurdles and regulatory challenges. The office did not respond to questions about Macron’s relationship with Uber.

Hired former government officials

In 2016 alone, Uber had a proposed global lobbying budget of $90 million US, according to the leaked documents. It paid friendly academics who published favourable research.

It hired an army of former government officials and political staff around the world, including in Canada.

Adam Blinick, currently senior director of public policy and communications, was initially hired onto Uber’s Canadian public policy team less than a year after quitting the Stephen Harper government as deputy chief of staff and director of policy to the public safety minister.

A spokesperson for Uber Canada said that Blinick was not involved with any matters related to Uber while in government and that he checked with the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner prior to accepting his first role outside government.

Jean-Christophe de Le Rue served as communications director to the federal public safety minister from 2013-15 before heading to Uber as a senior communications associate. An internal email noted he “will be helping us win hearts and minds, particularly in Quebec and Alberta. He will certainly have plenty of battles to fight — with court injunction and regulatory proceedings in Edmonton and tax authority raids and hundreds of car impoundments in Montreal.”

De Le Rue didn’t respond to CBC/Radio-Canada.

The leaked files also show the global scale of Uber’s ambitions. Memos mention hundreds of thousands of dollars in spending on consultants and lobbyists in countries like the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Jordan and Nigeria.

With files from Benoit Michaud, Scilla Alecci, Dean Starkman, Delphine Reuter, Ben Hallman, Jelena Cosic, Fergus Shiel, Mike Hudson, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Miguel Fiandor, Richard H.P. Sia, Hamish Boland-Rudder, Asraa Mustufa, Pierre Romera, Gerard Ryle, Antonio Cucho Gamboa, Joe Hillhouse, Tom Stites, Whitney Awanayah, Margot Williams, Soline Ledésert, Bruno Thomas, Caroline Desprat, Maxime Vanza Lutaonda, Damien Leloup, Adrien Senecat, Elodie Gueguen, Felicity Lawrence, Rob Davies, Jennifer Rankin, Aaron Davis, Robin Amer, Joseph Menn, Douglas Macmillan, Rick Noack, Linda van der Pol, Uri Blau, Dirk Waterval, Karlijn Kuijpers, Sara Mojtehedzade.

If you have tips on this story, email [email protected], DM on twitter @fredericzalac or call 604-662-6882.

For all the latest business News Click Here