The first metaverse experiments? Look to what’s already happening in medicine

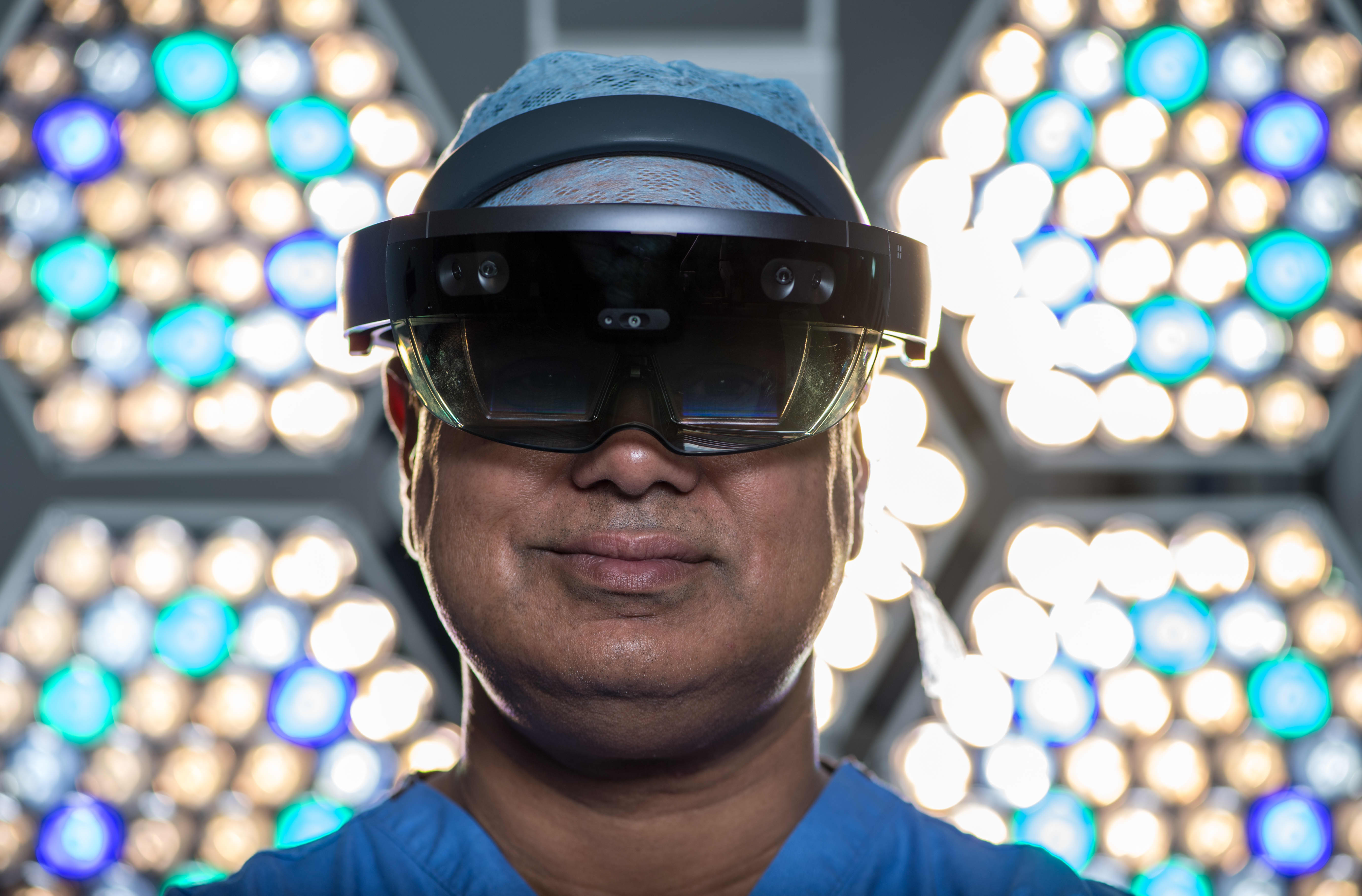

Surgeon Shafi Ahmed poses for a photograph wearing a Microsoft HoloLens headset inside his operating theater at the Royal London Hospital on Thursday, Jan. 11, 2018.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

The metaverse, the digital world’s Next Big Thing, is touted as the internet domain where animated avatars of our physical selves will be able to virtually do all sorts of interactivities, from shopping to gaming to traveling — someday. Wonks say it could be a decade or longer before the necessary technologies catch up with the hype.

Right now, though, the health-care industry is utilizing some of the essential components that will ultimately comprise the metaverse — virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), and artificial intelligence (AI) — as well as the software and hardware to power their applications. For example, medical device companies are using MR to assemble surgical tools and design operating rooms, the World Health Organization (WHO) is using AR and smartphones to train Covid-19 responders, psychiatrists are using VR to treat post-traumatic stress (PTS) among combat soldiers, and medical schools are using VR for surgical training.

Facebook, Oculus and Covid

Oculus technology is used at UConn Health, the University of Connecticut’s medical center in Farmington, Connecticut, to train orthopedic surgery residents. Educators have teamed with PrecisionOS, a Canadian medical software company that offers VR training and educational modules in orthopedics. Donning Oculus Quest headsets, the residents can visualize in 3-D performing a range of surgical procedures, such as putting a pin in a broken bone. Because the procedure is performed virtually, the system allows the students to make mistakes and receive feedback from faculty to incorporate on their next try.

Meanwhile, as the metaverse remains under construction, “we see great opportunity to continue the work Meta already does in supporting health efforts,” a Meta spokesperson said. “As Meta’s experiences, apps and services evolve, you can expect health strategy to play a role, but it’s far too soon to say how that might intersect with third-party technologies and providers.”

When Microsoft introduced its HoloLens AR smart glasses in 2016 for commercial development, early adopters included Stryker, the medical technology company in Kalamazoo, Michigan. In 2017, it began harnessing the AR device to improve processes for designing operating rooms for hospitals and surgery centers. Because ORs are shared by different surgical services — from general surgery to orthopedic, cardiac and others — lighting, equipment and surgical tools vary depending on the procedure.

Recognizing the opportunity the HoloLens 2 provided in evolving OR design from 2D to 3D, Stryker engineers are able to design shared ORs with the use of holograms. The MR experience visualizes all of the people, equipment and setups without requiring physical objects or people to be present.

Zimmer Biomet, a Warsaw, Indiana-based medical device company, recently unveiled its OptiVu Mixed Reality Solutions platform, which employs HoloLens devices and three applications — one using MR in manufacturing surgical tools, another that collects and stores data to track patient progress before and after surgery, and a third that allows clinicians to share a MR experience with patients ahead of a procedure.

“We are currently using the HoloLens in a pilot fashion with remote assist in the U.S., EMEA and Australia,” a Zimmer Biomet spokesperson said. The technology has been used for remote case coverage and training programs, and the company is developing software applications on the HoloLens as part of data solutions focused on pre- and post-procedures, the spokesperson said.

Microsoft’s holographic vision of the future

In March, Microsoft showcased Mesh, a MR platform powered by its Azure cloud service, which allows people in different physical locations to join 3-D holographic experiences on various devices, including HoloLens 2, a range of VR headsets, smartphones, tablets and PCs. In a blog post, the company imagined avatars of medical students, learning about human anatomy, gathered around a holographic model and peeling back muscles to see what’s underneath.

Microsoft sees many opportunities for its MR tech, and in March secured a $20 billion contract with the U.S. military for its use with soldiers.

In real-world applications of AR medical technology, Johns Hopkins neurosurgeons performed the institution’s first-ever AR surgeries on living patients in June. During the initial procedure, physicians placed six screws in a patient’s spine during a spinal fusion. Two days later, a separate team of surgeons removed a cancerous tumor from the spine of a patient. Both teams donned headsets made by Augmedics, an Israeli firm, equipped with a see-through eye display that projects images of a patient’s internal anatomy, such as bones and other tissue, based on CT scans. “It’s like having a GPS navigator in front of your eyes,” said Timothy Witham, M.D., director of the Johns Hopkins Neurosurgery Spinal Fusion Laboratory.

At the University of Miami’s Miller School of Medicine, instructors at the Gordon Center for Simulation and Innovation in Medical Education utilize AR, VR and MR to train emergency first-responders to treat trauma patients, including those who have had a stroke, heart attack or gunshot wound. Students practice life-saving cardiac procedures on Harvey, a life-like mannequin that realistically simulates nearly any cardiac disease. Wearing VR headsets, students can “see” the underlying anatomy which is graphically exposed on Harvey.

“In the digital environment, we’re not bound by physical objects,” said Barry Issenberg, MD, Professor of Medicine and director of the Gordon Center. Before developing the virtual technology curriculum, he said, students had to physically be on the scene and train on actual trauma patients. “Now we can guarantee that all learners have the same virtual experience, regardless of their geographic location.”

Since it was founded in 1999, the University of Southern California Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT) has developed VR, AI and other technologies to address a variety of medical and mental health conditions. “When I first got involved, the technology was Stone Age,” said Albert “Skip” Rizzo, a psychologist and director for medical virtual reality at ICT, recalling his tinkering with an Apple IIe and a Game Boy handheld console. Today he uses VR and AR headsets from Oculus, HP and Magic Leap.

Rizzo has helped create a VR exposure therapy, called Bravemind, aimed at providing relief from PTS, particularly among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. During exposure therapy, a patient, guided by a trained therapist, confronts his or her trauma memories through simulations of their experiences. Wearing a headset, the patient can be immersed in several different virtual scenarios, including a Middle-Eastern themed city and desert road environments.

“Patients use a keyboard to simulate people, insurgents, explosions, even smells and vibrations,” Rizzo said. And rather than relying exclusively on imagining a particular scenario, a patient can experience it in a safe, virtual world as an alternative to traditional talk therapy. The evidence-based Bravemind therapy is now available at more than a dozen Veterans Administration hospitals, where it has been shown to produce a meaningful reduction in PTS symptoms. Additional randomized controlled studies are ongoing.

As Big Tech continues to build out the metaverse, alongside software and hardware companies, academia and other R&D partners, the health-care industry remains a real-life proving ground. “While the metaverse is still in its infancy, it holds tremendous potential for the transformation and improvement of health care,” wrote Paulo Pinheiro, head of software at Cambridge, U.K.-based Sagentia Innovation on the advisory firm’s website. “It will be fascinating to watch the situation unfold.”

For all the latest Technology News Click Here