Teacher Burnout Is Real. Will It Be the Next Phase of the Great Resignation?

It took just a simple question for Andria Nelson to grasp how different the world of education was from everything else. Nelson had quit her teaching job just months into the 2020-21 school year and taken a job as a communications specialist for a transportation company. Her innocent request — seeking someone to cover for her so she could go to the bathroom — raised some amused eyebrows around the office.

“People in that office laughed at me because I asked permission for everything,” said Nelson over Zoom. “I couldn’t believe what it was like working in an office from being a teacher.”

Nelson’s story is a familiar one. She fell in love with teaching as a special education associate back in 2012, leading her to pursue a teacher’s certification. By the fall of 2020, she’d spent more than seven years teaching language arts to middle school students. Along the way, she’d also coached girls soccer, cross-country and track. She was teaching accelerated English and global studies with a teacher partner and had seemingly found her calling.

Then things began to change. For every education professional, the way working as a teacher goes from dream job to recurring nightmare looks different. For Nelson, it was the anxiety of coming back to in-person teaching during the pandemic while having an autoimmune disease, being harassed by another teacher and not getting help from the school administration.

In November 2020, Nelson quit. “My mental health is not OK,” she told her principal, “and now I’m starting to lose my physical health.”

Nelson’s departure illustrates the compounding complications of the COVID-19 era, which are taking a massive toll on teachers nationwide. But the coronavirus is just the latest crack in a system badly in need of an overhaul. Teachers were already burning out amid ever-increasing demands to do more, with little support and with stagnating salary increases. Every year, fewer people are choosing to join a profession that’s hardly evolved in 50 years, and vacancies are on the rise.

Now the Great Resignation has many fearing a mass exodus out of the teaching ranks. Experts argue, however, that there isn’t yet empirical evidence that teachers are quitting in record numbers. Still, even the most skeptical admit that the possibility of seeing an unprecedented wave of teacher resignations before this school year ends or the next one starts has never felt more real. And the potential consequences for students, schools, families and the country as a whole couldn’t be more serious.

“Teacher resignations pose an incredible challenge to public schools,” said Anne Claire Tejtel Nornhold, a former middle school teacher who’s now in charge of implementing a new classroom structure at Baltimore City Schools, known as Opportunity Culture, in an effort to increase teacher retention.

When a teacher quits, she noted, students end up being taught by less experienced teachers, which may result in kids learning less. Parents frustrated by the erosion of the learning environment, she added, may consider private school or homeschooling instead.

“We do know from rigorous empirical evidence that disruptions from teacher turnover have a negative effect on student test scores,” added Dan Goldhaber, director of the National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (CALDER) at the University of Washington. “And that test scores are predictive of a variety of later life outcomes, like the probability of employment and labor market earnings.”

At stake is also the emotional and educational recovery of an entire generation of students who’ve had to endure the pandemic from a unique perspective, switching back and forth between in-person and remote learning, navigating mask mandates and the politics associated with them, dealing with uncertainty about vaccines — or lack thereof — all on top of worrying about their own academic future.

Failing to modernize the teaching profession could make it even harder to attract a new generation of talented individuals into the classroom, said Brent Maddin, executive director of the Next Education Workforce Initiative at Arizona State University, a national organization devoted to innovation in the field of teaching. “Who wants to join the profession typified by the headlines of the last few weeks?”

When teacher resignations go viral

Following the reaction of her new co-workers to the quirks formed by her prior life as a teacher, Nelson posted a video on TikTok with the caption, “When teachers change careers,” along with hashtags like #teachersoftiktok, #leavingteaching and #mentalhealthmatters. In the video, you can see Nelson at her desk pretending to ask her manager who she needs to contact if she has to take a bathroom break.

“I can just go?” Nelson says in disbelief. The video, posted in September, went viral and has since accumulated more than 1.1 million views and been shared more than 15,000 times. Nelson’s TikTok post became part of a trend of teachers posting similar videos of themselves quitting their jobs, which spilled over into the news.

“Teacher’s TikTok goes viral after telling class she’s quitting due to pay,” reported local TV station KRQE in Albuquerque, New Mexico. “For some teachers, it’s QuitTok, not TikTok,” said local Salt Lake City station 2KUTV.

More recently, news reports about teacher resignations have seemed to go beyond anecdotal social media posts to suggest a larger, more worrisome trend. The demand for more qualified teachers was already there. A 2016 study by the Learning Policy Institute projected that by 2020, an estimated 300,000 new teachers would be needed per year, and that by 2025, that number would increase to 316,000 annually.

COVID only made things worse. A survey published in early February by the National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union, found that more than half its members intend to leave education sooner than planned because of the pandemic — “a significant increase from 37% in August,” the association said.

Beyond the TikTok viral videos and the agonizing news headlines, there seemed to be enough evidence to express real concern about a looming tsunami of teacher shortages and resignations threatening to disrupt the school year even further than the numerous waves of coronavirus variants already had.

“I don’t know how much longer we will have teachers who will put up with the pressures coming from all different angles,” J.M., a middle school teacher from Austin, Texas, who’s been teaching for 11 years, said in an email. (She asked CNET to withhold her full name because she didn’t want to compromise her position at school.) “I am at a ‘steady’ school (one where academic success is high and behavior is mostly under control), and I hear of lots of teachers here who are ready to walk off the job at any given moment.”

“People are ignoring the news that is making headlines already,” said J.J., another middle school teacher from Austin, who’s been teaching Spanish at the high school and middle school levels since 2006 and recently began to consider leaving the profession. (She too asked that CNET withhold her full name.) “Teacher burnout has become even more real since the pandemic began.”

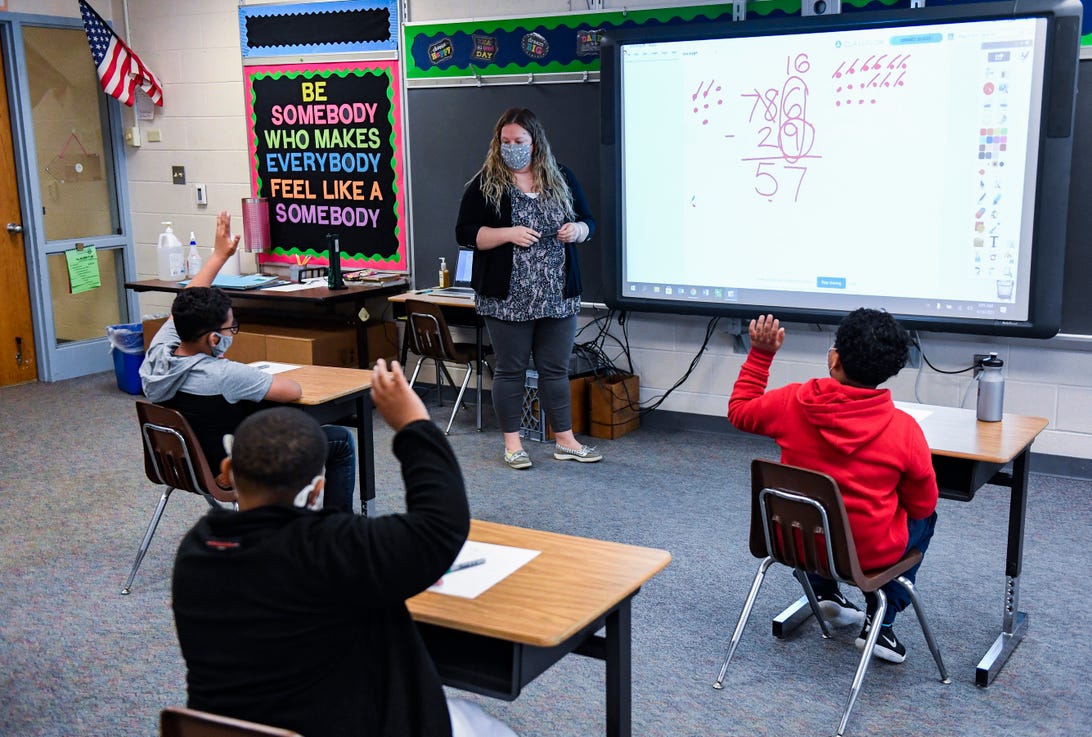

A teacher interacts with students virtually while sitting in an empty classroom during a period of nontraditional instruction at an elementary school in Kentucky.

Jon Cherry/Getty Images

In a December letter, US Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona urged school administrators across the country to “use resources from the $122 billion made available through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 to ensure that students have access to the teachers and other critical staff they need to support their success during this critical period.” He cited surveys that showed severe staffing shortages and difficulties hiring qualified teachers.

A big reason? It comes down to money.

Why teachers want to quit

When I asked one teacher who left her job before the holiday break, and three others who are considering quitting, about their motivations, each mentioned several different reasons. Money was the one common factor.

“The salary and level of appreciation are much lower than what we deserve,” said J.M., one of the Austin schoolteachers. “Last year, the year we were teaching online, I ended up teaching four extra classes from February through May. I was compensated for only one of those.”

A 2016 national survey of first-year college students conducted by UCLA’s Cooperative Institutional Research Program found that just 4.2% of them intended to major in education, down from 11% in 2000 — and the lowest point in 45 years.

“Salary is one huge part of it,” Bryan Hassel, co-president of Public Impact, a nonprofit organization working with school districts to improve education for low-income and other underserved students, said over Zoom. If teacher pay had kept up with the increase in education spending over the last 50 years, he explains in one of his studies, the average annual teacher pay would be nearly $140,000 today. Instead, the national average annual teacher salary in the 2019-20 school year was just more than $63,000, according to the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics.

“[Teacher] wages have been relatively flat as compared with professions that require similar levels of expertise, certification and education,” Jess Gartner, a former school teacher and CEO of Allovue, a technology company that builds solutions for K-12 finance, said over Zoom. “Overall, teacher compensation has actually increased, but the majority of the increase is going into either pension or health care benefits. Costs have risen so dramatically they’ve effectively depressed real wages that teachers are seeing in their paycheck.”

“After having to pay more bills with a growing family, I have become more aware of how little I make in comparison to others while I have more educational background than many,” said J.J., the middle school teacher from Austin, who has a master’s degree.

According to the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, by the school year 2017-18, almost 60% of all teachers across the country had a post-baccalaureate degree. And with over 3.5 million teachers in the country, teaching “is far and away the largest single profession in America that requires a bachelor’s degree,” David Rosenberg, partner at Education Resource Strategies, said over Zoom. ERS is a national nonprofit that helps school leaders think about using their resources differently and reimagine the job of teaching.

But it’s not just teacher salaries that have failed to keep up for years. “We’ve been demanding more of teachers through all that time,” said Hassel. “Standards are higher” these days.

Nelson, one of the teachers whose videos went viral on TikTok, said she had a student in her seventh-grade class who read at a second-grade level, while also having other students in the same class who were reading at a post-high school level. “When you have 36 students in a room, it’s incredibly difficult to help a second-grade-level reader.”

Over time, as a country, and particularly at the state level, we’ve also tightened up the rules for entering the teaching profession, according to Chad Aldeman, policy director of Edunomics, a center at Georgetown University focused on the study of education finance. “It’s been all with good intentions, raising the bar to become a teacher,” Aldeman said over email. “But that means there are more subspecialty areas to earn licenses, more requirements to become a teacher than there used to be.”

All these efforts have had unintended negative consequences, Maddin said over email, rendering the teacher’s job “quite frankly, untenable… one that people are more likely to run from than to.”

But it’s not only the lack of salary competitiveness versus increased expectations that keeps the teaching profession anchored in the past. It’s the nature of the job itself.

A profession that hasn’t evolved in decades

Over the last century, the way we communicate with each other and how we consume media and live our lives has been dramatically transformed. Yet teaching has largely remained unchanged.

“The majority of children in the US learn in schools that replicate the dominant industrial model of education that was designed over 100 years ago to prepare most children to work in farm and factory jobs,” Jenee Henry Wood, head of learning at Transcend, a national nonprofit helping schools reimagine education models, said in an email.

In almost every other profession that requires a degree, people have the opportunity to learn on the job, take on more responsibility, advance and earn more money. That’s not the case with teachers. “In teaching, you pretty much have the same job for your whole career,” Public Impact’s Hassel said. “Unless you become a principal or leave altogether… there’s not a lot of advancement opportunity.”

Most school districts and schools in the country keep operating under the traditional one-teacher, one-classroom staffing model, several experts said, which not only creates an isolating and challenging experience for most teachers, but is also a recipe for disaster when something unexpected happens — like a pandemic.

The traditional school model “creates 3.5 million points of possible crisis [across the country] each day if individual educators don’t show up for work,” Maddin said.

As multiple schools across the country could attest in recent months, the pervasiveness of the one-teacher, one-classroom model exacerbates staffing issues in an emergency. “There’s no backup or support system,” said Aldeman.

But the challenges presented by the traditional staffing model aren’t just logistical. They may also be holding both teachers and students back.

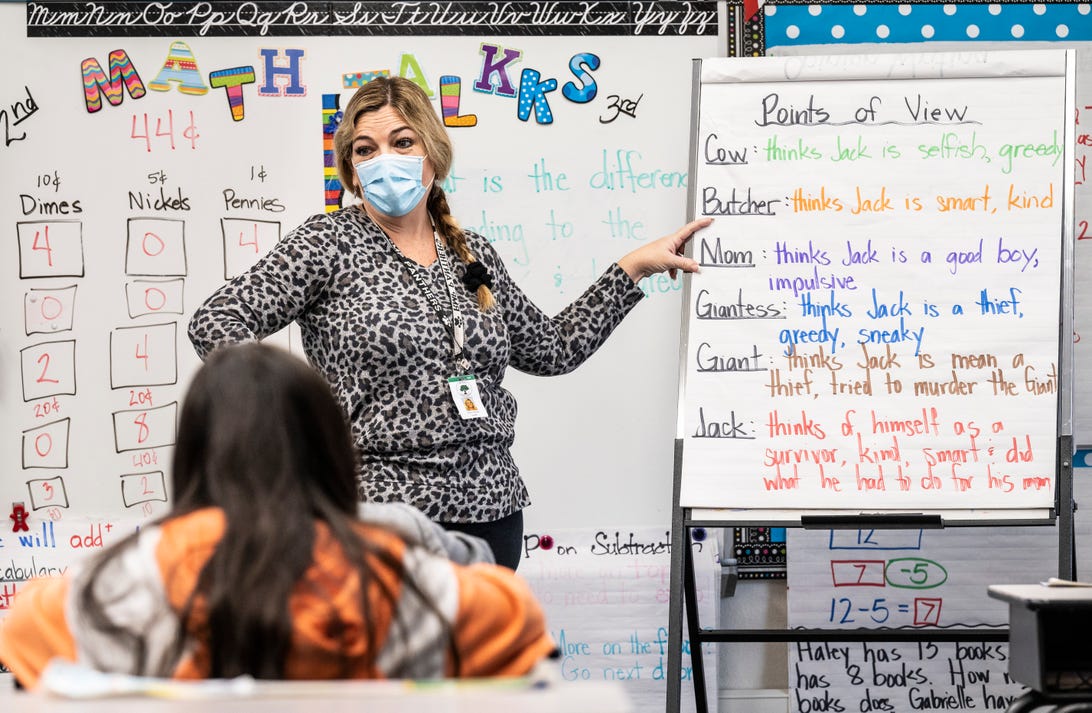

Fourth graders in Pennsylvania.

Getty Images

For students, the old model means, “They’ll only experience excellent teaching in a subject once every few years,” said Hassel from Public Impact. “It makes great teaching a scarce resource that only a select fraction of students receive.” For educators, he added, it “severely limits the opportunity to learn on the job from peers, or advance in their career and earn more while continuing to teach.”

The way the teaching profession is structured right now, Rosenberg from ERS said, requires teachers to be heroes. “We have to structure the work so people can be successful,” he said.

“Teacher shortages will only continue to get worse until we fundamentally redesign our school staffing models,” said Maddin. “We don’t have just a teacher shortage problem. We have a workforce design problem.”

Bringing a reset to the role of teachers

A number of initiatives across the country are helping schools reimagine how teachers work. Public Impact’s Opportunity Culture initiative is one of them. “Teachers join small teams, three to eight teachers, led by a multi-classroom leader, a teacher who has prior high student growth and takes on the leadership of that whole team,” Hassel said.

These teachers get more support than they normally would in a traditional model where they’re working mostly by themselves with their 20 or 30 kids. “They’re working as a team and they’re getting better results,” Hassel said. Public Impact’s research found that the multiclassroom leader’s student growth — their ability to score higher in tests — can jump from the 50th percentile to above the 70th percentile.

Team leaders earn, on average, between 12% and 20% above their normal salary, Hassel said. About 50 school districts around the country have embraced Opportunity Culture’s model, and 90% of participant schools in the program are Title I, meaning they serve low-income communities.

ASU’s Next Education Workforce Initiative is another example. Its program consists of building teams of educators to deliver deeper and personalized learning for pools of kids larger than those in the traditional classroom staffing model.

“Imagine you have four teachers with 100 kids, collectively responsible for all those kids,” Next Education Executive Director Maddin said. “Like literally every other profession, we can now start to allow teachers to develop specialization and expertise. They wouldn’t have to be great at everything, but there would be a set of things that they would be exceptionally good at.”

Updating the structure of the classroom can also help schools react more effectively to staff shortage emergencies, such as those caused by the pandemic. A team-based approach, Aldeman said, can help the system “continue to function well even if an individual member leaves.”

A different approach to salary increases

Beyond modernizing the teaching job, increasing teacher salaries across the board seems an obvious first step to thwart further resignations, and some states, like New Mexico, are already raising pay. Not all the experts I interviewed agree, however. One of the reasons retaining teachers and attracting new ones remains endemically challenging, some argue, is that teacher salaries are basically the same for everyone in most school districts, regardless of area of expertise or teaching environment.

As part of his research, Goldhaber looked into the number of vacancies schools in Washington state have had, going back 30 years. Vacancies for elementary teachers, he found, have always been low while those for STEM and Special Ed teachers have always been very high.

“This pattern exists because teacher pay is not differentiated,” Goldhaber said over Zoom. Raising all teacher salaries would help schools draw more talented people into the teaching profession, he argued, “but I also strongly believe that across the board, pay increases do not make sense.”

Goldhaber advocates for increasing pay at the beginning of teachers’ careers, where retention rates are low, and for people with STEM training. “You’re trying to attract people who have been able to do well enough in math and science classes to teach, but those are folks that outside of teaching have good labor market opportunities.”

Teaching in California.

Getty Images

School districts usually try to pay special ed, STEM or English learner teachers a little bit more because those professionals are harder to recruit, said Sasha Pudelski, director of advocacy at AASA, the School Superintendents Association. But sometimes salary negotiations are constrained by other factors, including union negotiations around salary schedules.

The current teacher shortage dynamic is a magnified version of the dynamic from before, especially at “high poverty schools [and among] high school teachers [in] specialized roles,” said ERS’ Rosenberg. Staffing for those roles is particularly difficult in “communities where there’s already high turnover, which feeds itself because high turnover means you hire early career teachers and they also have high turnover,” he said.

That’s why Goldhaber would “make it relatively more desirable to teach disadvantaged students, because it’s chronically harder to staff disadvantaged schools and districts.” A study published in 2019 by ASU found that teacher turnover rates were 50% higher in Title I schools than other schools. Turnover rates among Title I math and science teachers were nearly 70% higher.

The Great Resignation that’s coming — or not

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking and parents and school administrators keep bracing for a tide of teacher resignations. So far, however, the available data and expert analysis suggest otherwise.

Last year, ERS conducted a study among six school districts across the country to see how turnover had changed compared with pre-pandemic years. “In all six districts, turnover going into fall 2020 went down,” said Rosenberg, one of the authors of the study.

Reports from the Bureau of Labor Statistics published in the last six months reflected turnover rates in the private sector reaching new highs, leading to talk about the Great Resignation. But “we actually don’t have any empirical evidence suggesting that teacher turnover is rising this year,” Georgetown’s Aldeman said.

In reality, said Goldhaber, there’s not a single comprehensive national data set about teacher employment. Besides surveys from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the other source of the best information about teacher attrition is states’ administrative databases. “We would only know if people are resigning en masse in the ’21-’22 school year next fall,” he said over Zoom.

But many experts I interviewed think this time it could be different. The labor market is very tight, and employees have more bargaining power than before. “It’s a good time for people who want to leave teaching to leave,” the University of Washington’s Goldhaber said.

It’s tricky because, despite all its problems, teaching can also be rewarding. When I asked the teachers about their reasons to stay, all of them replied with their own version of, “I don’t think I will find a more meaningful job than this one” (as Austin teacher J.J. put it in an email).

“The relationships and interactions with my students are what drives my passion for my job and brings me joy,” A.C., another teacher from Austin, who’s been teaching for about 25 years, said in an email. The pandemic has taken a toll on her. Now “the things about teaching I never thought about start finding real estate in my brain. … Every other week or so, when I am feeling particularly down and out, I entertain the idea of leaving.”

Will she end up joining teachers who are leaving? “Probably not,” she replied. “I teach because of the kids. They are not going anywhere so, how can I?”

After eight months at the transportation company, Nelson is teaching again. She’s now offering online courses for a tutoring company, and she misses the classroom and her middle school students. “They’re the love of my life. I love their stinky little hilarious selves.”

Money was never the reason she left. “I was OK with [earning] $55,000 and I loved my job every day and seeing those kids every day. Sure, it’d be great to make $80,000 a year for it, but that’s not why I was doing it.”

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.

For all the latest world News Click Here