Social care in Scotland at ‘very real risk of collapse’ this winter amid staff exodus and soaring insurance costs

SOCIAL care in Scotland is at “very real risk of collapse” this winter amid rocketing insurance premiums and a workforce exodus, MSPs have been told.

Donald Macaskill, chief executive of Scottish Care, warned that the sector is now “haemorrhaging” staff to better-paid and less stressful jobs in retail and hospitality, and the coming months will see “more and more providers going to the wall”.

Dr Macaskill, whose organisation represents independent care providers who make up around 70 per cent of care homes and home care services in Scotland, told Holyrood’s Covid-19 Recovery Committee, that insurance premiums for care homes had soared from an average of £3000-£5000 a year in 2019 to £30,000 now, on top of rising costs for heating and electricity.

“That makes a small, family-run business virtually impossible to sustain,” he added.

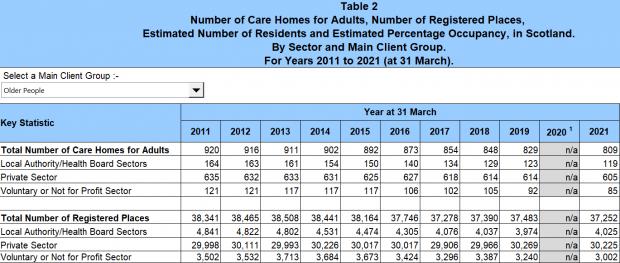

It comes after days after statistics showed that 20 care homes for the elderly in Scotland had been lost in the two years to March 2021, with the rate of closures nearly doubling in the private sector compared to pre-pandemic levels.

READ MORE: Alarm over hundreds of avoidable deaths in young Scots with epilepsy

Dr Macaskill told MSPs that nine out of 10 providers surveyed during the summer said they were struggling to recruit, with 40% of people invited to interview failing to turn up and 60% of those appointed quitting within the first six months.

“During the first wave of the pandemic workforce stability was in the high 80 per cents,” he said.

“Very few people left the sector, they were dedicated, they stayed, they were sacrificial in their working.

“Now, however, we are facing in social care the biggest workforce crisis that the sector has ever experienced.”

Dr Macaskill’s concerns were echoed by Dr Andrew Buist, chair of BMA Scotland’s GP committee, who said tackling the recruitment and retention crisis in social care crisis must be the “top priority to resolve this winter”.

A shortage of social care provision in the community and care home availability has been blamed for exacerbating bottlenecks in the NHS through avoidable admissions of frail elderly people into hospital, and subsequent bed blocking when patients well enough to be discharged are delayed by a lack of adequate social care provision.

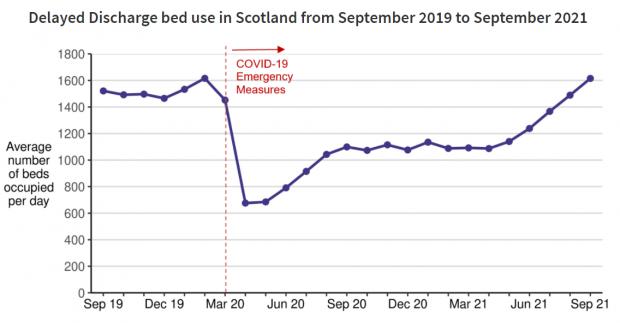

The average number of acute hospital beds being lost each day to delayed discharge has climbed steadily from around 1,100 in March to 1,600 by September.

Dr Buist added: “We must do something to support the [social care] workforce, otherwise the burden that will create in the rest of the system will take down anything else that we try to do.”

READ MORE: What’s really behind the worst winter crisis facing Scotland’s NHS?

The Scottish Government’s £300 million winter plan includes includes £48m to enable employers to raise the pay for adult social care workers to at least £10.02 per hour, which Dr Macaskill said was a “step in the right direction”.

However, he said it was “simply not sufficient” to compete with other sectors.

He said: “The NHS and local authority partnerships are engaged in a massive recruitment drive at the moment.

“In the last week, a rural care home in Forth Valley reported to me that they have lost three nurses and four carers, all of whom have gone to the NHS in the local area. A care provider in Edinburgh has lost 15% of its home care staff because they’ve gone to work for the local authority.

“Now we’re not wanting to stop people moving on but if we are paying the same amount of money to somebody who is a domestic member of staff in the NHS as we are to somebody who is delivering professional, skilled care, who is qualified and regulated, then that lack of parity means that no matter how much we give to the social care system we will always bleed out talent and our skills elsewhere.

“Undoubtedly, another factor is that retail and hospitality are dramatically short of staff in no small measure due to their inability to recruit internationally.

“So, particularly in rural parts of Scotland, our members are saying to us they’re losing care staff to secure, less stressful environments which are not able to recruit internationally.”

READ MORE: Is it time to reform the care sector in Scotland – and if so, how?

Dr Macaskill added that the sector is having “real problems recruiting and holding onto senior staff” such as care home managers, whose hourly rate under the National Care Home Contract – the funding agreement negotiated between independent providers and the Scottish Government – is £13.50.

He said one council was offering more than that – £14 an hour – for jobs in its home care service.

Dr Donald Macaskill, chief executive of Scottish Care

Dr Donald Macaskill, chief executive of Scottish Care

“I know finance experts will say the cupboard is bare; well, there is a very real risk of social care collapse this winter unless we intervene with additional resource both to retain staff – and I know Unison has suggested retention payments – but also a starting salary which properly recognises the amazing skilled job which care is.”

Dr Macaskill also pointed to recent UK research which estimated that round-the-clock nursing in a care home costs £1000-£1200 per resident, per week.

However, under the National Care Home Contract – which is currently being renegotiated – local authorities pay just £750, leaving older people with savings and assets such as property to shoulder an increasing share of the funding gap through higher fees.

“That is unfair and inequitous, especially for women and men unfortunate enough to develop dementia and who in the later stages of their illness will have no choice but to receive 24/7 specialist care in a care home,” said Dr Macaskill.

Source: Scottish Care Homes Census

Source: Scottish Care Homes Census

The Scottish Government says the new £10.02 hourly rate for social care workers matches the salary for Band 2 NHS staff, and that it is also investing a further £100m to maximise capacity in care home services and for ‘step down’ care to enable hospital patients to temporarily enter care homes, or receive additional care at home support, without any financial liability.

For all the latest health News Click Here