Review of Mike Brearley’s Turning Over the Pebbles — A Life in Cricket and in the Mind: A second bite of the cherry

In the 1960s, Mike Brearley, having topped the Civil Services exam was interviewed for the post of British spy. The unexpected is our companion through much of what Brearley calls ‘a memoir of his mind’; his range of achievements, from the academic to the professional is astonishing. Yet, the tone of Turning Over the Pebbles: A Life in Cricket and in the Mind alternates between diffidence and confident self-awareness, contributing to its charm and importance.

The Latin word for ‘pebbles’ gives us ‘calculus’, the study of continuous change. It may not be a coincidence that it figures in the title of the book.

The novelistic descriptions of people and places here suggest that the world of fiction-writing might have lost a major figure because of Brearley’s other callings, as philosopher, cricketer and psychoanalyst. This is a book of history, of literature (the chapter on Henry James is pure gold), music and theatre too, provoking in our minds those lines from Oliver Goldsmith: And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew,/that one small head could carry all he knew.

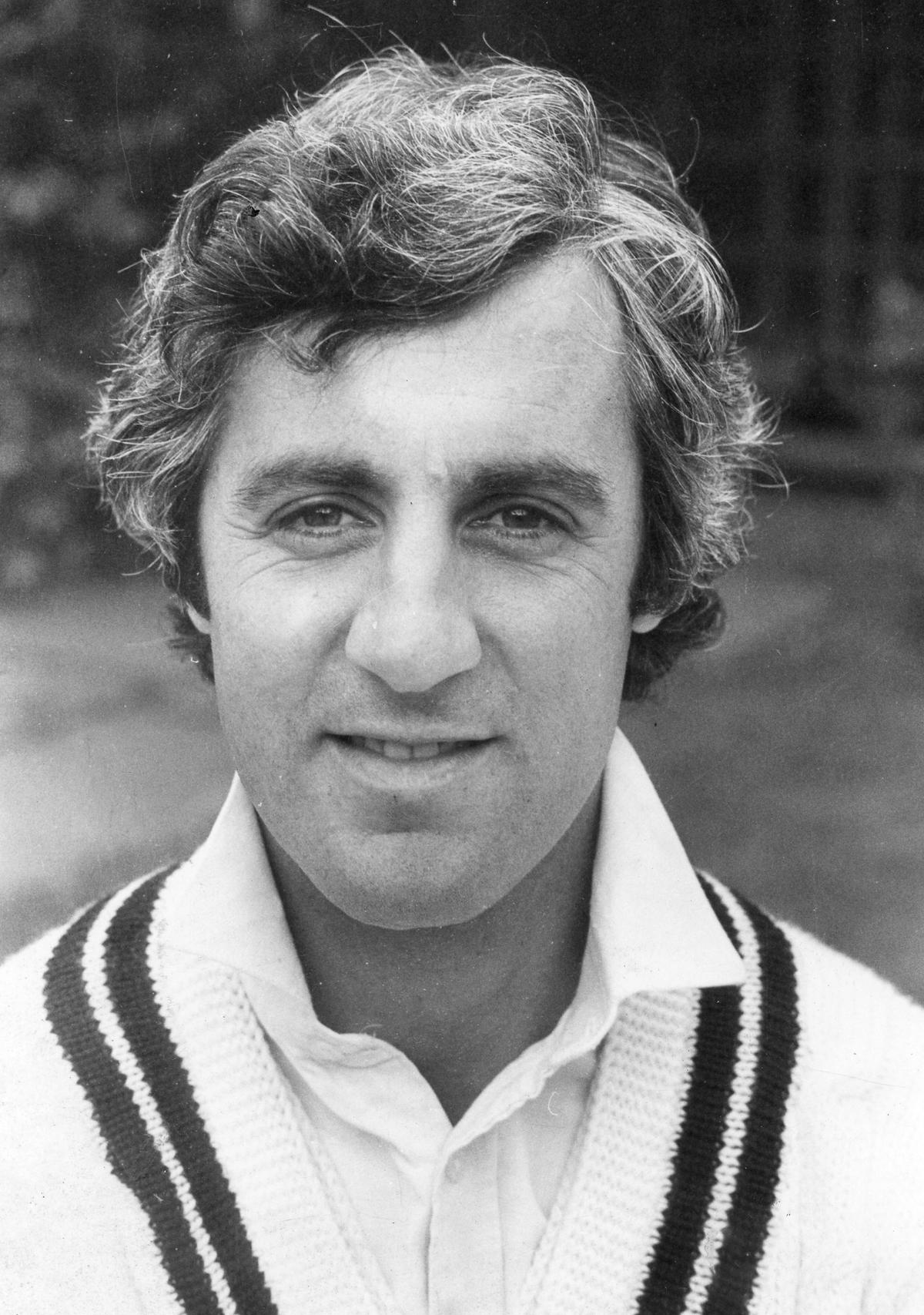

Picture of Mike Brearley taken in 1978.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Story of a life

What is also remarkable about the book are the things it is not. It is not patronising or superior, it is not centred around one individual or event but radiates outwards in a manner at once inclusive. It is not a scholar posturing or a sportsman complaining. It is not about any one thing, but a story of a life — with all its lack of order and inevitability — well lived.

England captain Mike Brearley (centre) leaves the field as spectators rush on at the Oval on August 29, 1981, in London.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Brearley’s wife Mana once told a friend there were two Mikes, the cricketer and the psychoanalyst. Which do you prefer? asked the friend. “The cricketer,” Mana replied. As this book shows, the cricketer cannot be understood or cherished without the other Mike. One enhances the other.

“This book,” says Brearley at the start, “is in a sense a story of a quest, to get hold of myself, to be not too much a stranger to myself… to turn over the pebbles to see what lies underneath — murky detritus and/or richer patterns?” It is, he says, a book of second thoughts, a second bite of the cherry: not only the original experience, but a new take on it.

England captain Mike Brearley during a warm-up session in Manchester, in 1981.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Open to any page, and Brearley emerges as unique. While batting against Michael Holding the great West Indies fast bowler, he relaxed by humming the opening bars of Beethoven’s Razumovsky Quartet, Op. 59. While playing for Middlesex, he would sometimes write Shakespeare’s sonnets on his hand and learn them by heart. While keeping wickets for Cambridge, he kept up a conversation on philosophy with first slip Edward Craig, later Knightsbridge Professor of Philosophy at the university.

‘Humour of cricket’

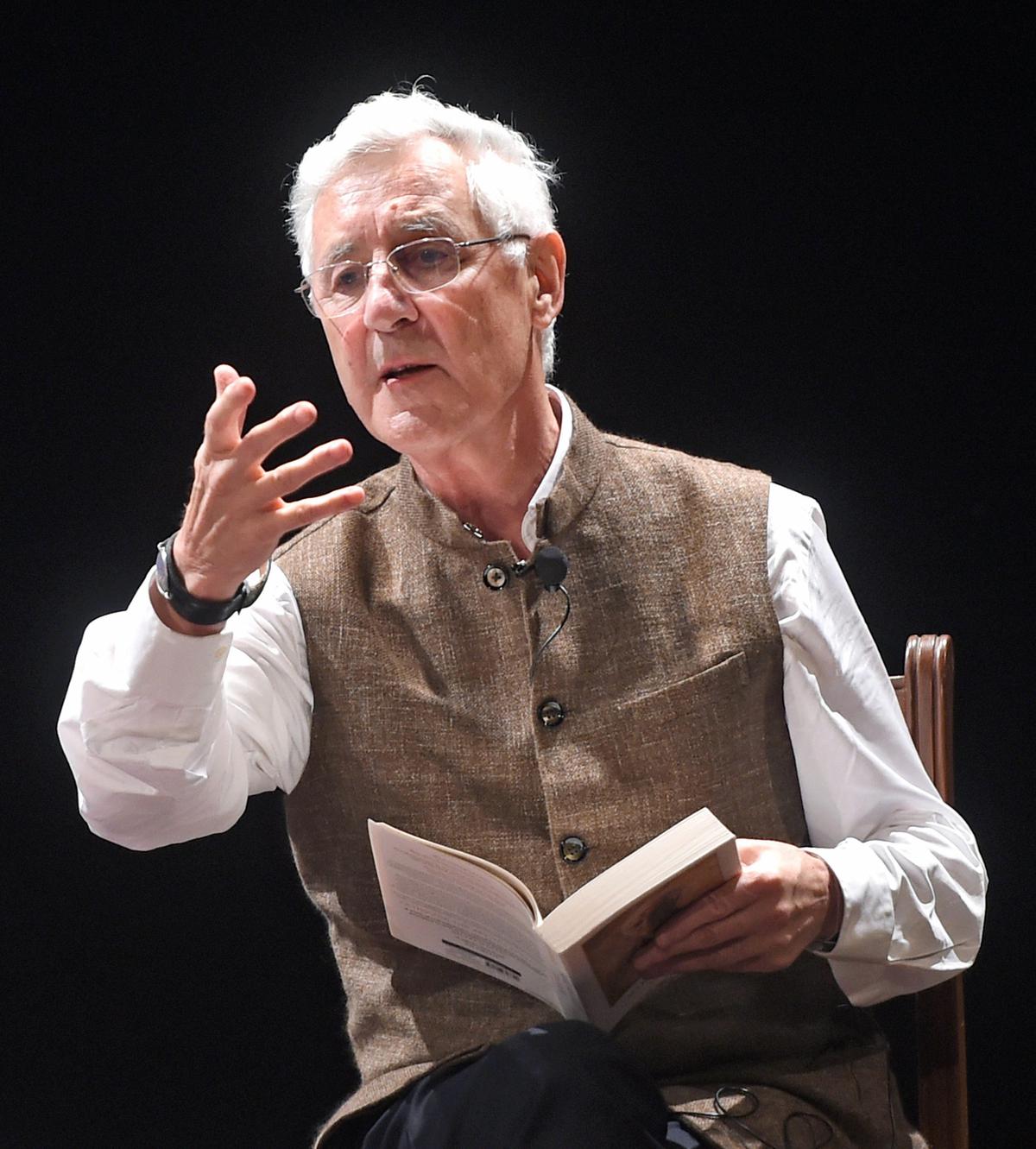

Mike Brearley during his visit to Chennai in 2018.

| Photo Credit:

Bijoy Ghosh

Cricketing stories and anecdotes (“I enjoy the humour of cricket”) don’t come across as an intellectual slumming it. Obviously, the game is a part of Brearley’s life, but not the only part. Slices of his other lives have appeared in his classic books on cricket — The Art of Captaincy and On Form are among the top 10 books on the game — but here he puts everything in context. The greatest captain in the game led with a mixture of instinct and intellect, winning 18 of 31 for England and losing just four.

We are all liable to the risk of a blindness that comes from sophistication, says Brearley. He himself avoids this trap by being aware of it, and thanks to a degree of self-analysis not common in modern literature. It is as though Montaigne captained his country’s cricket team during breaks while writing his Essays.

Brearley is almost embarrassed to focus on his accomplishments, but less reticent about his fears and traumas. He is both reclining on the psychoanalyst’s couch, talking about his dreams, as well as sitting behind it interpreting them. It is a double act he carries off with honesty and wit.

Mike Brearley at an event in Mumbai.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The psychoanalysis came later, after three years as a lecturer in philosophy. In retrospect, however, everything seems to point towards a career in psychoanalysis. Brearley links his life experiences, his academic training, and his wide reading with this eventual profession. “This valuing of the examined life,” he writes, “is what most obviously links literature, philosophy and psychoanalysis.” In another place he says, “In moves towards complexity or simplicity, music and analysis can mirror each other.”

When Brearley applied to train at the Institute of Psychoanalysis, he was accepted because the committee felt captaining a professional cricket team had relevance to the kind of experience required for the job.

Philosophy didn’t hurt either. Both for what it said and what it provoked in Brearley. Wittgenstein’s image of philosophy as a way of showing the fly out of the fly-bottle is unsatisfactory, says Brearley. “It sounds as though it might be done once and for all simultaneously. Reality is more complex; our reasons for being trapped are more deep-seated, and the ways in which resistance to insight and to change occurs are multiple.”

He acknowledges that Wittgenstein’s philosophy helps loosen our shackles, going on to say, “while the philosopher’s anxiety has a kinship with that of the neurotic or even psychotic parts of ourselves, healing is akin to psychoanalytic work.” The common ground between Freud and Wittgenstein, and the later psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion who modified some of Freud’s theories is discussed in a refreshingly original way. Rather than sexuality, Bion placed attitudes to knowledge at the heart of the theory.

‘Organ recitals’

Brearley celebrated his 81st birthday in April this year, having gone through illnesses (discussed in the book) like everybody else. He says when he meets old cricketing colleagues, most discussions begin as organ recitals: the prevalent organs being hips, knees, backs, shoulders, eyes, ears.

Turning Over the Pebbles, for those who know Mike Brearley mostly as a great captain and writer on cricket is a separation of his personality into other fascinating parts. For the writer himself it is a great synthesis, a bringing together of his personalities. His use of poets and musicians, cricketers and novelists, psychologists and philosophers, historians and writers on religion towards this end makes the journey fascinating.

Turning Over the Pebbles: A Life in Cricket and in the Mind; Mike Brearley, Hachette India, ₹799.

The reviewer’s latest book is Why Don’t You Write Something I Might Read?

For all the latest Sports News Click Here