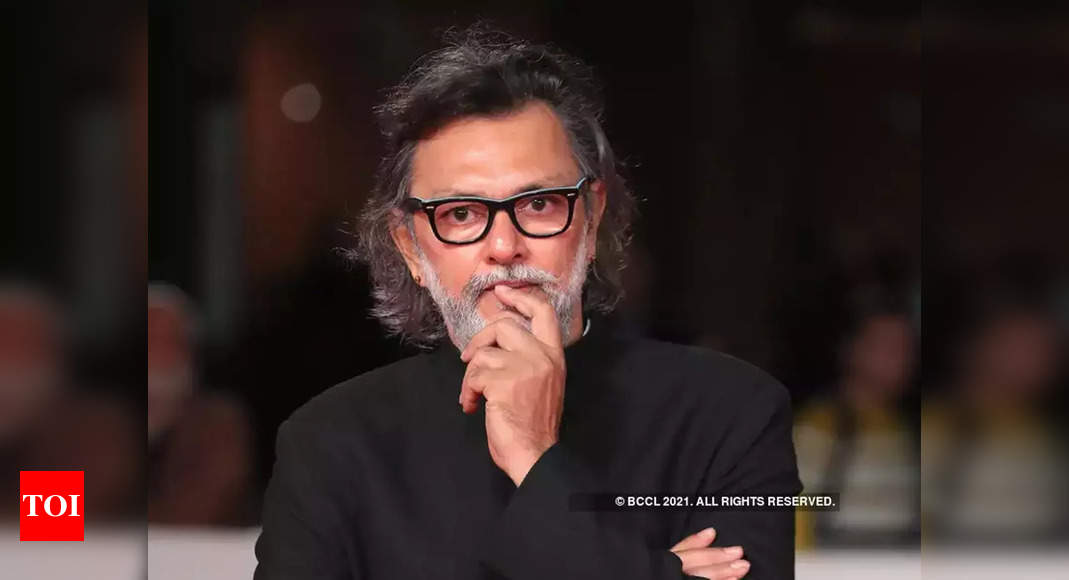

Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra: I poured my heart out and stood naked in the book – Times of India

What is your process of filmmaking? How did you learn the tricks of the trade and what compelled you to take up this vocation?

The technique came to me very naturally. I don’t have to think about the camera and the lens. I was relating well to the actors (Manoj Bajpayee, Raveena Tandon, Amitabh Bachchan) and was able to extract performances that were out-of-the-box. In hindsight, I realised that the real hero of the film was the writing. Writing for movies and writing otherwise is very different. I was not even writing those days. so I thought to myself ‘Bhai agar film banani hai to likhna sikhna padega (If I want to make films, I’ll have to learn to write).’ So I started reading.

I had never been to a film school, nor assisted anyone. In fact, the first time I saw a camera was for my own shoot when I hired it. I was also editing my ad films a lot in London and would take my films there for editing, because it was all new-age technology, and it felt right. There I chanced across a lot of film books. That’s when I started reading about screenplay, and realised that I didn’t know anything. Along with reading, I also started watching a lot of world cinema. It was at this time that I also started writing ‘Rang De Basanti’.

One of the authors I looked out for was Syd Field–the guru of screenplay writing in Hollywood. Books on Indian cinema were non-existent. The only things you could pick up were books on personalities like Amitabh Bachchan. I was dying to know the journey of the author, why they made the film, what was going through their minds, the idea behind the films, and all such things that I had seen in Kurosawa’s books. There was a lovely book called ‘Something like an Autobiography’, ‘Kosinski and Kosinski’. So, I think the seed was born there.

More likely than not, the movies got connected with my childhood and growing-up years. Going to Air Force school and MiG crashes led to ‘Rang De Basanti’, I was brought up in New Delhi, so ‘Delhi 6’, fondness for sports and listening to the horror stories of partition, which was ‘Bhag Milkha Bhag’. So it kept going back and forth to all the incidents that impacted me.

How did you decide to collaborate with Reetaji (Ramamurthy Gupta)? What was your process during the collaboration because both of you are creative people?

It was absolutely amazing because she is an amazing human being and extremely patient. We would talk a lot. Whenever I had a gap from shooting, I would call her and say, ‘Let’s speak some more.’ She would make pointers and write it all down and I would take things from my childhood that only I knew. It was a lovely give-and-take relationship. We kept passing the baton back and forth and finally things were taking shape. After getting in touch with the publishers and graphic designers, we decided to let this book also be a visual experience because I have a visual mind and don’t think in words.

Let’s talk about the title ‘The Stranger In The Mirror’. Reetaji has put how it came about in a tongue-in-cheek manner. How did you relate to it?

To be honest, our working title was ‘Interval’, as cliche as it sounds. My friends would ask me why I am writing it now, ‘

Picture abhi baaki hai’. So, I thought of calling it ‘Interval’ and moving in that direction. But, as it unfolded, and I poured my heart out and stood naked in the book, I noticed that mirrors kept popping up in my films rather subconsciously at particular moments.

In ‘Bhag Milkha Bhag’, when he messes up at the Olympics, I wrote a scene where he slaps himself because he is looking at himself in the mirror and he doesn’t like that person. ‘Delhi 6′ was all about mirrors. The music CD was not the actress’ face, it was actually a mirror. So if you bought the CD,

apni shakal dekhte hai usme (You see your own face on it).

I normally have conversations with myself every morning in the mirror and I always find someone else there. It’s almost like that is the real person and I am becoming someone else. Who is the stranger–The person in the mirror or the one standing here? That is the confusion I try to solve.

The structure of your book is very interesting. Like your movies, your book is very non-linear. Did this come about organically or did you decide this is how it is going to be?

I don’t think life is linear. For me, it doesn’t work like that. You travel to work, you see something and it reminds you of something else and you jump back in time. After becoming a student of cinema, I found that the most unique thing about it was editing. Cinematography was born from photography which was born from painting. Art direction is born from art. Wardrobe and fashion have been there forever. The only thing born after cinema was editing. I once did a workshop with a master editor, Walter Merch. He edited ‘The Godfather’ and ‘Apocalypse Now’, he is “the guy”. I asked him, how do you make the cut? Is there a pattern? He said, ‘No, I take the cut emotionally”.

A lot of my technicians are ready to kill me because I don’t always follow technique; not every shot has to be a master shot.

Jo galat bhi hai, sahi hoga editing me (Whatever is wrong can be corrected in the editing). I also learned that time is irrelevant when you are making cinema. Someone shuts a door and opens it in another country and the audience accepts it. Also, when it comes to novels, different readers are imagining the same book in their own way. When you are writing a playright, you watch it unfold in front of you on a stage and there is a direct connection to the actor, but when you are writing a screenplay, it is actually a story told in pictures. I experimented with ‘Mirzya’. Of the 2.20 hour film, 1.10 hours was silent and it didn’t work. People were not used to silent films.

Now that we are talking about ‘Mirzya’, is there a dilemma that all creative people face–Do you have to be good, you are too good to be popular, or you have to be commercially successful. Because there is so much money involved in filmmaking, the commercial part does weigh heavy and you have been brutally honest about how you have made your films. How do you deal with the commercial aspect and how do you then place yourself as a filmmaker?

I was in Delhi recently and my sister asked me the same question. She said, ‘

Tumhari problem kya hai yaar? Koi ache actor le aur tere ko film banane aate hai, to chal hit bana (What’s your problem dude? You know how to make films; just take some good actors and deliver a hit).’ She loves me and cares for me and wants to see her brother delivering hit after hit. So I asked her to tell me her favourite five films. She picked her favourites. I then told her that ‘Mother India’ was made in the late ‘50s, another in the late ’60s, ‘Lagaan’ was made in the ’90s; she wasn’t picking a particular time. I asked her if ‘Guide’ was a box office hit or failure and she didn’t know.

So for me, the true test of cinema is when it stands the test of time. ‘Delhi 6’ did roaring business on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday and collected over Rs 44 crore. On Monday it just fell flat and we had no clue what happened; we had already had a success party. It took me years to understand what had happened. Months later, the film was released on Channel 4 in the UK and got the maximum rating for any Hindi film. And now that I see it, it is drawing back viewers slowly. Surely it is not dead and in fact, it has not even plateaued yet.

You’ve been totally honest about what you went through after ‘Delhi 6’ and it takes a lot of courage to put it all out in your memoir. Was there a time when you thought that maybe you should filter some things out or were there things that you put in and then later took out?

No. I just poured my heart out. That is how I make movies and that is how my friends and family know me.

This book is more than just a memoir. It is documentation about your process, about how each movie was made, how you got your actors on board, how the music was created. When an aspiring filmmaker or film student reads this, what would you like them to take away from this?

Who am I to tell them? It is up to them. In a book written by Francis Ford Coppola’s wife, she writes about the time when he was working on ‘Apocalypse Now’ and started with a certain budget but the budget increased tenfold. Think of it as someone making a film like our ‘Mughal-e-Azam’. The whole crew went to Indonesia, shot elaborate scenes and yet, the film tanked. But, before that, when he was casting for the film, he knocked at every door. He was Francis Ford Coppola, who made ‘The Godfather’ and yet, everyone kept lying to him or refusing.

Steve McQueen told him he was taking a break for a year. The next thing he knew was that Steve was shooting for his next film after a week. He had 11 Oscars at the time and he took them all and threw them on the streets. The statues all broke and his wife later went and collected it. Despite it all, he went on to make his film.

It is from these things that you learn. When he re-released the film years later, it became a huge hit and it is a classic now. So, you just have to keep following your passion and instinct.

What I find fascinating about your journey, is that you come from Delhi and are the proverbial outsider, put in your years in advertising, learned on the job. Do you think your years in advertising gave you an advantage?

On the contrary, it worked against me. In advertising, you are under the umbrella called marketing. You are adding emotion into a product and that becomes your universe. When you shift to movies, it is something else altogether, and much more basic. Films are about what is inside you. The things that make you. The shampoo doesn’t make you.

In this book, you say that you came to Bombay and pursued advertising. You went up to Gulzar on a whim and said you wanted to make ‘Devdas’. Do you still want to make it?

Yes, sure. It is an evergreen piece of literature. Why not? Actually, I just wanted to meet Gulzar saab; ‘Devdas’ ek bahana tha, par acha bahana tha (Devdas was merely an excuse, and a good one at that). I bribed the watchman, went up to his house, Putti saab opened the door. I told him that I had an appointment, and he said, ‘No, you don’t’. I asked him to check the diary and he told me ‘I write the diary and you don’t have an appointment’. Then I think I called him ‘uncle’ and said ‘Please, likh lo na (Please, give me an appointment)’. He finally agreed and after some time Gulzar called me in.

I remember, he was sitting against a window and had a halo around his head. I was shaking inside-out and when he asked me what I wanted, I said, “Will you write Devdas for me?” We spoke about his take on Devdas. He said, ‘I had started making ‘Devdas’ with Dharmendra and Hema Malini and in 10 days it folded. I realised it was not an easy film to make and that it was not for me. Why you do want to make it?’

I had watched the film and I always felt that they had got the story wrong. The book was actually about an adolescent boy, who falls for a lady much elder than him. When it didn’t work out, he became an alcoholic and died with all that love in his heart. I thought that maybe the hero should be younger,

but humare yaha aisa hota nahi hai (that’s not how the society works). I explained how, when it comes to love, it is the women who have more strength than the men. He liked the idea and I told him that when I get the money to fund the film, I’ll come back to him. Twenty-five years later he gave me ‘Mirzya’.

Another film that I know was close to your heart was ‘Samjhauta Express’ that didn’t get made. Would you want to make it now? It sounds like a fascinating story from the little that I read about it in the book…

It is quite a complex one and the first film I wanted to make. I had worked on the script and Kamlesh Pandey, who also worked on ‘Rang De Basanti’, had written the film. I remember going to AR Rahman, who even composed something for me. It was supposed to be my first film and Abhishek Bachchan’s debut. We were both young and spent a lot of time on it. He even maintained a diary on what his character’s thoughts were. This went on for a good 6-8 months. But the movie was not allowed to be made. It was not that it wasn’t made, but the system prevailed over us.

You know how the mind thinks…people advised that Abhishek will not be accepted by the audience if he plays an anti-national or a Pakistani terrorist. I was asked what I was doing and told to do something else. I don’t think I’ll make this movie, ever. For me, we are both equal villains for each other; this whole rhetoric that they are bad and we are good is something I cannot accept. That is not how the world works. If you go on the other side of the fence, you hear another story.

A lot has happened since you made ‘Rang De Basanti’ 15 years ago. Do you think the youth have a cause today?

For the uninitiated, I was making a documentary, ‘Mamuli Rang: The Little Big Man’ which was inspired by Dr Verghese Kurien. I had made some ad films for Amul and had gone to present them. He saw it and liked it; I stayed there for six months to make the documentary. Kamlesh would come there as he was writing the documentary about the Milk movement. Both of us had nothing to do in the evenings in Anand village. That’s when Kamlesh and I bonded and decided to make ‘Young Guns of India’ on the arms revolution which started in 1919 and peaked in 1933, when Bhagat Singh took his walk to the gallows. I hit a spot with him and realised that they were his favourite characters too. So, we did our research, and he wrote a lovely script that we named ‘Young Guns of India’. It originally started with Hartal Singh who threw the bomb… then Chandrashekar Azad and Bhagat Singh and many others. All these guys were young. The average age for when they died for the country was 23-and-a-half. Then we read about their philosophy, which was so amazing. Bhagat Singh said, “I don’t want independence from the

goras to be enslaved by the

kalas,” and his prophecy came true.

So that was the idea; I wanted to make it very cool without slow-motion and definitely without singing songs. Coming from the ad world, we got together with a group of youngsters in a Mumbai hotel. I began reading the script and they rejected it altogether. That time, they were called the MTV generation and aspired to go to America, wear Nike; I thought that these Bombay youth want to be millionaires before they are 25, let’s go back to Delhi where I belong and have a heart-to-heart discussion. But even there, they rejected the idea in just five minutes. They were of the impression that they knew it all. We went into depression and three days later Kamlesh said he couldn’t drop this idea, so, we decided to turn it around. These youngsters were not seeing themselves on screen. First, we had to make them see that, and then take them for a thrilling ride.

The plot of the MiG aircraft came about because the planes were crashing and I happened to see a documentary. The then Defence Minister, George Fernandez, took a joyride in a MiG and declared them safe. So I kept throwing ideas at Kamlesh, and he turned the whole story around within a week and gave me a new storyline.

In the British library in Paddington, I went to research on revolutionaries. After seven days of researching, I found a thin book on Bhagat Singh and Chandrashekar Azad, in which they were called terrorists. So one country’s revolutionary is another country’s terrorist, and we see that reflection happening within our country. We’ve seen that in Kashmir so many times. So Kamlesh turned the story around. He sharpened the screenplay. Denzel, a copywriter from our advertising days, came on board and asked why these characters can’t talk like we are talking. He added the dialogues into the script.

You reworked the ending of ‘Delhi 6’…

I went into a dark hole, not because the film tanked on a Monday, or because critically, I was getting bashed. I could not understand it at the time. I took respite in alcohol. Six months later, I woke up with a clear head and called up Vinod Pradhan, my DOP. I told him, ‘We need to shoot for ‘Delhi 6′.’ He didn’t ask any questions; just wanted to know when it was happening. Six months later, we shot for three more days.

The original screenplay was Asthiya visarjan (immersion of the ashes). It was happening at Ganga near Haridwar. And Abhishek’s voiceover went, ‘Ye jo asthiya hai, ye naye Asthiya.” So a dead man is talking to you. So now, when you see, the protagonist in the film, who is half-Hindu and half-Muslim, comes from the US, because his dadi wants to come back. The fish wants to come back to the water, where it will die. So, you know that in the end, this one is going to die. But somewhere, I lost conviction. Later, I thought ‘

Ye khatam karna bahut zaruri hai (it is important to finish this)’ otherwise it will not get out of my system and will not be able to make my next film.

So we re-edited the film and just for fun, submitted it at the Venice film festival, which immediately accepted it. It got a very good reception there.

As the audience is maturing these days, is demand for commercial cinema going down? Are cost and technology correlated?

I don’t think cost and technology are related. The cost of the film comes from what the story is. If you are making a ‘Baahubai’, there will be a certain cost because it employs very modern-day tech, but if you are making a ‘Vicky Donor’, then you don’t need as much money. But both are equally great films. Yes, the bandwidth is greater than it used to be in the initial days. The discipline has changed and evolved a lot more.

I don’t understand what commercial cinema is. Is it good cinema or bad cinema? The fact that you spend money on something, makes it commercial. In the words of all the film legends, ‘You make what you have to make, and it will turn out to be what it has to be’.

I can’t hide behind the thought that I am making art and this is commercial filmmaking. The moment I approach cinema through the tunnel vision of commerce, there will be loads of compromises, and then there is no fun. As you spend your life on it, it becomes an extension of what you are.

When you make films, does the first cut directly land on the editing table?

Yes. I don’t have monitors on my shoot, where there is a screen and everyone watches what happened. Your actor is acting, you are directing, you don’t have to double-check; it’s all in the moment. After that, I leave it to the editor; I don’t even enter that room, except when called.

I think finally, the screenplay is rewritten on the edit table. First, the author writes his version, then the cameraman films it in a way he interprets it, the actors add their touch to it. AR Rahman and Shankar will interpret it differently and you’ll get different music. Gulzar

saab and Javed (Akhtar)

saab will write different lyrics for the same thing. Then the editor comes and tries to make sense of it and rewrites it all over again. That is the beauty of cinema–it is a collaborative thing.

For all the latest entertainment News Click Here