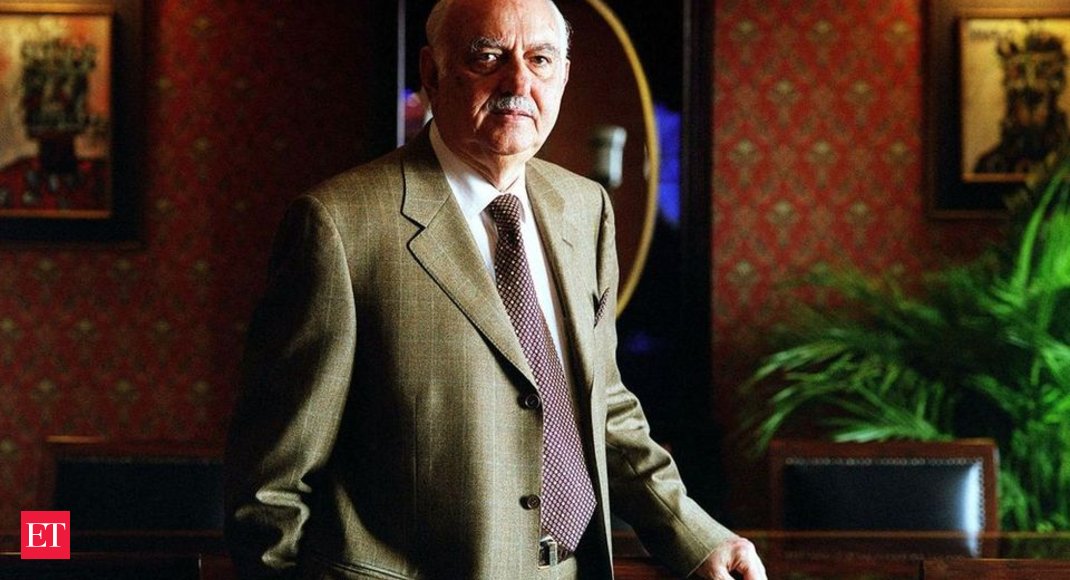

Pallonji Mistry, the billionaire caught in Tata feud, dies at 93

A company spokesperson confirmed the death of the Indian tycoon after social media posts on the news spread.

Mistry and his family control the Shapoorji Pallonji Group, which started more than 150 years ago and today employs more than 50,000 people in over 50 countries, according to its website. Its landmark projects include the Reserve Bank of India and the Oberoi Hotel in Mumbai and the blue-and-gold Al Alam palace for the Sultan of Oman.

Mistry accumulated a net worth of almost $29 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, making him one of the richest men in India and in Europe. He surrendered his Indian nationality and became an Irish citizen in 2003 through his long marriage to Dublin-born Patsy Perin Dubash.

Most of the family wealth, however, derived from being the largest minority shareholder — 18.5% as of early 2022 — in Mumbai-based Tata Sons Pvt., the main investment holding company for India’s largest conglomerate.

That stake proved to be a double-edged sword for the media-shy Mistry when the shock ouster of his son Cyrus as Tata Sons chairman in 2016 triggered a very public, years-long courtroom and boardroom battle between two of India’s most-storied corporate clans.

The country’s top court ruled in 2021 that Cyrus’s ouster was legal and also upheld Tata Sons’s rules on minority shareholder rights, which made it difficult to sell shares without board approval. That meant the stake, worth almost $30 billion in early 2022, was basically illiquid.

Early Partners

The family business was founded in 1865, when Pallonji Mistry’s grandfather started a construction business with an Englishman. The initial project was the first reservoir in Mumbai, then known as Bombay. The company began doing business with the Tata family in the 1920s; both families are Zoroastrians whose ancestors fled Persia to India to escape religious persecution.

Mistry was born on June 1, 1929, in Mumbai. His father, Shapoorji Mistry, worked for the family company, which the son joined in 1947.

He led the company’s expansion into the Middle East, including Abu Dhabi, Qatar and Dubai, in 1970. It won a contract to build the Sultan of Oman’s palace in 1971 and many ministerial buildings there.

His management style and desire to expand globally was in sharp contrast to that of his father, who traveled abroad just twice to help some family members seek medical treatment, according to the 2007 book “Moguls of Real Estate,” by Manoj Namburu.

Unlike his father, who exercised personal control over the smallest detail and had his engineers apprise him every day on projects, Mistry delegated authority and only retained supervisory and planning powers.

To protect the company’s reputation, Mistry was often willing to complete a construction project even at a loss, according to “Moguls of Real Estate,” which cited Zafar Iqbal, a former chief executive officer of SP Group.

Under his watch, the business developed into a conglomerate that included real estate, water, energy and financial services. Its stake in Forbes & Company Ltd. provided access to textile, engineering, home appliance and shipping businesses, while it held a majority stake in Afcons Infrastructure Ltd., which built projects in India.

Tough Times

To Indians, besides the Oberoi Hotel and RBI’s building in the nation’s financial hub, the company is also known for building the Mumbai World Trade Centre in 1970 and the Imperial, two 60-story residential towers, in the city in 2010. It also built an 80-acre (32-hectare) information-technology park called Ozone, in the western Indian city of Pune. That was an offshoot of a 110-acre stud farm Mistry bought in the 1980s, which went on to breed Indian Derby winning stallions, according to Namburu’s book.

The family’s stake in Tata Sons increased as the company built car factories and steel mills for the group. His father also bought stakes from Tata family members over the years. Meanwhile, the Tata portfolio expanded to more than 100 companies, including brand names such as Jaguar, Land Rover, Tetley Tea and Corus Steel.

India’s news outlets called Mistry “the Phantom of Bombay House,” the Tata group’s head office, because he was rarely seen there and because of his quiet demeanor and avoidance of the media. The family is generally secretive and even such details as when he and his wife married are not publicly known.

Mistry took a backseat after Shapoor, his eldest son, took over as chairman of SP Group companies in 2004.

Boardroom Coup

Cyrus became the Tata Sons chairman in 2012, succeeding Ratan Tata. But he was removed four years later in a boardroom coup led by Tata Trusts, which owned 66% of Tata Sons and was controlled by Ratan Tata. The dispute snowballed with allegations of mismanagement and suppression of minority shareholder rights. The 2021 court ruling in Tata’s favor left burnt bridges between the two families, which had been partners for 70 years.

After his Tata stint, Cyrus went on to set up a venture capital firm, Mistry Ventures LLP.

Despite a diversified set of businesses, the SP Group was forced to look at asset sales as it faced a cash crunch, burgeoning debt and even a payment default in 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic hit its core real estate operations. In October 2021 a unit of Reliance Industries Ltd. agreed to acquire 40% of Mistry’s Sterling & Wilson Solar Ltd.

In addition to his two sons Mistry had two daughters, Laila and Aloo. The latter married Noel Tata, the half-brother of Ratan Tata, who was named chairman emeritus of Tata Sons.

For all the latest world News Click Here