How should he be remembered?

On July 26 of this year, the Jackie Robinson Museum had its soft opening. The SoHo ribbon-cutting occurred 14 years after plans for the cathedral to honor the man who broke baseball’s color barrier and ended racial segregation of Black players relegated to the Negro Leagues were first announced. The Jackie Robinson Foundation curates the museum’s collection of artifacts, with 100-year-old Rachel Robinson creating the foundation honoring her late husband months after his passing. The Manhattan museum, which opened to the public in September, is around eight miles from where Ebbets Field, the stadium in which Robinson manned second base for the Dodgers, formerly stood, just to the east of Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

Rachel watched the museum’s dedication from her wheelchair, then clamped down on a huge pair of scissors for a ribbon-cutting ceremony to mark the museum’s long-awaited opening. If there’s an expert on all things Jackie, it must be the woman he was married to for 26 years until his death, 50 years ago on Oct. 24, 1972. They wed in 1946, the year before his Major League debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and after his time as a standout athlete at UCLA, and military service. And Rachel knew throughout her husband’s personal and professional life pre-MLB, he was routinely called Jack.

It’s ambiguous as to what Jack Roosevelt Robinson himself preferred and unfortunately, he’s not around to answer that question himself. Saturday marks the 50th anniversary of Robinson’s final public appearance, nine days before he passed. It was to throw out the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the 1972 World Series between the Reds and Oakland A’s in Cincinnati. The honor coincided with the 25th anniversary of his MLB debut earlier that year. Robinson used his final sentence in the limelight at the pregame event to criticize the league, despite accepting a plaque to commemorate the occasion: “I’m extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon but must admit I’m going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third-base coaching line (where managers used to patrol) one day and see a Black face managing in baseball.”

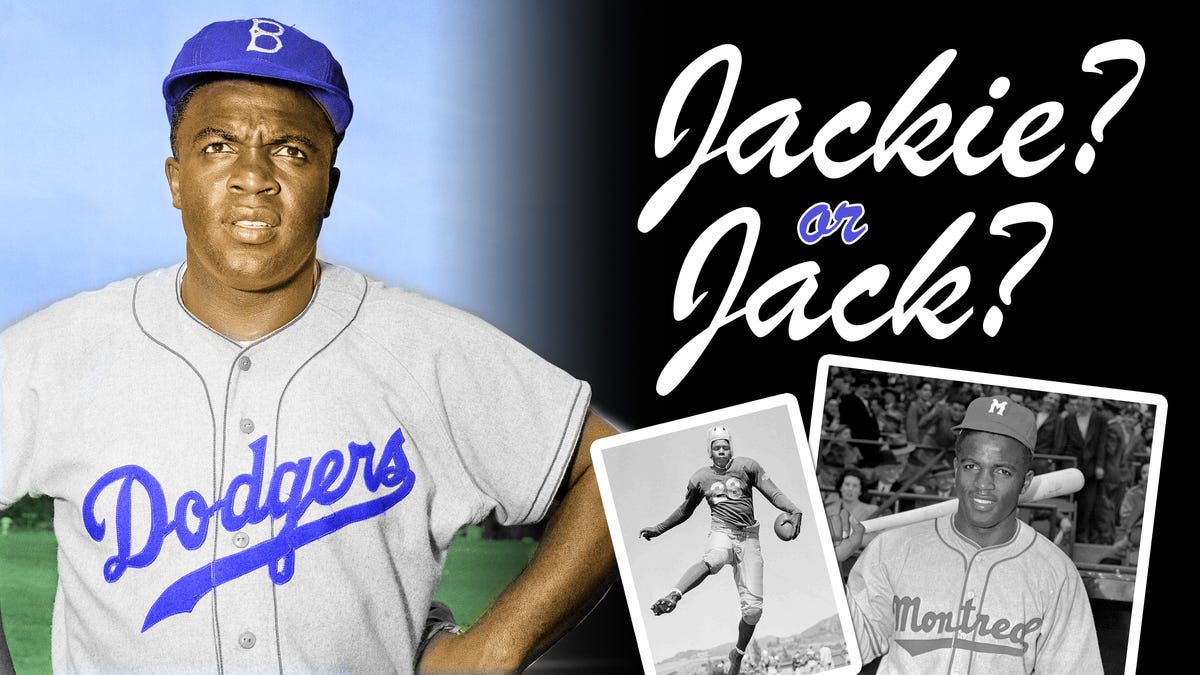

The fact that a debate exists as to whether Mr. Robinson preferred his birth name or almost-exclusively used nickname makes it worthy enough to ask why Jackie became his moniker at all. MLB has never celebrated Jack Robinson Day. It’s Jackie Robinson Day, held annually on April 15. A representative for the Jackie Robinson Foundation told Deadspin the following in regards to the museum: “Mr. Robinson is only referred to as Jack when it is something said by Mrs. Rachel Robinson or in reference to his early childhood before he was known as Jackie,” Beth Zielinski, director of Data Management for the foundation, said via email.

And when you listen to Rachel refer to her husband, it’s Jack, not Jackie. On his original Hall of Fame plaque, presented to him in 1962, there’s no mention of “Jackie.” He’s identified as Jack Roosevelt Robinson. According to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Robinson’s plaque was updated in the late aughts to include information about his breaking the color line, and then the “Jackie” was added underneath his birth name. That plaque still hangs in Cooperstown. The original was kept in storage and was recently loaned out to the Jackie Robinson Museum.

So the question is, did Robinson even have control over his own name, whether he wanted to be called Jack or Jackie?

Michael G. Long, co-author of Call Him Jack: The Story of Jackie Robinson, Black Freedom Fighter, told Deadspin his understanding of the Jack vs. Jackie issue, saying, “It’s a really interesting question and it’s not absolutely easy to answer. When he was born, his mother named him Jack Roosevelt Robinson. And he had a brother named Mack and a brother named Frank. And she clearly intended to name him Jack, rather than Jackie.”

There are also several documented signatures from Robinson where he formally wrote his first name as Jack. Next to his photo in a high school yearbook, he signed Jack Robinson. At Pasadena City College, he signed photos as Jack Robinson. In the Army, he penned letters as Jack Robinson. In 1946 as a member of the Triple-A Montreal Royals, he autographed baseballs as Jack Robinson. He signed checks as Jack Robinson, with his checkbook belonging to Jack R. Robinson. The nameplate on his desk as an executive for Chock Full o’ Nuts coffee? Jack. And the Baseball Hall of Fame has a number of Robinson’s correspondence, and according to their library, letters from Robinson to family and friends he signs Jack, all others, such as to fans and media, it’s Jackie.

If the longtime Dodger had a formal preference, why is Jackie used nearly universally?

The suffix “ie” or “y” has been used in America to generate familiar nicknames for kids, i.e. Bobby and Susie. But in the case of Black athletes in the middle 20th century, it was typically used to infantilize them in order to make them appear less threatening to white audiences. Emasculating Black men by referring to them as ‘boys’ or by using boy-like nicknames, was common pejorative dating back to slavery.

“This huge myth develops around Jack Robinson and it’s the myth of him being a nonviolent soldier in the war against racism,” Long told Deadspin. “This is the year he turns the other cheek. This is the year he gets up, dusts dirt off his uniform, and just soldiers on nonviolently when people shout slurs at him. He’s not threatening in 1947. He’s not a threat to white America because he soldiers on nonviolently as a peaceful warrior. And so there’s this myth of a collected, calm, cool, smiling, and non-threatening Jackie that really rises up to 1947. That’s the year when people in America and across the world begin to know him as Jackie Robinson. It’s a diminutive form of the name Jack Robinson. And it’s closely aligned with the myth of a peaceful man who smiles while people hurl racist slurs at him.”

Robinson knew it wasn’t paramount what his name was; he knew his actions as the first Black man to break the color barrier were more important. If he clapped back as the prominent non-white disruptor of America’s pastime, that’s all anyone would talk about. Once his career started in Brooklyn, he did adopt the “ie” for his signatures on baseballs. Long cites that sports writers covering Pasadena’s junior college and UCLA, especially white ones, were the first to refer to him as Jackie Robinson publicly. Beat writers for MLB and the Dodgers followed suit.

“It’s hard to say that it’s innocent because they saw this Black guy and his name was Jack and they just started calling him Jackie. They just completely changed his name. It’s not what he went by,” Lou Moore, history professor at Grand Valley State and author of We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality, told Deadspin. “But at the same time, I’m not sure they meant harm out of it. It’s just kind of one of those things that happens with writers. (They) see this young Black kid and (they’re) going to call him Jackie and not Jack. And that’s just what sticks. But he’s always been Jack.”

How much of a difference do two letters really make? Consider the case of the late Dick Allen.

There was an attempt to refer to Dick Allen, the Phillies star of the ‘60s and ‘70s who was Black, as Richie, a move largely facilitated by Philadelphia’s sports writers in the 1960s, who portrayed Allen as a troublemaker who expected preferential treatment in the aftermath of a brawl with white veteran Frank Thomas. It was revealed years later that Thomas had directed racial slurs at Black teammates and the fight started because of one racist statement made at Allen. In response to being involved in the skirmish, the push to re-name him Richie came about to make him appear less threatening, instead of his preferred name of Dick. As Allen put it: “To be truthful with you, I’d like to be called Dick,” he said in 1964. “I don’t know how the Richie started. My name is Richard and they called me Dick in the minor leagues. It makes me sound like I’m 10 years old. I’m 22.”

And there was certainly a push to refer to Roberto Clemente, the Hall of Fame Pirates right fielder, as Bob or Bobby Clemente, again using the diminutive suffix, and Americanizing his name.

“I can’t say we have a standard on this and had not given it much thought,” Dr. Raymond Doswell, vice president of Curatorial Services at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City told Deadspin about Jack vs. Jackie. “I think there are formal times when his proper name is most appropriate (like when referring to birth and death, on plaques or honorific things). However, if listed on a document or historic record, like a newspaper or letter, we would go with what was printed, which was often Jackie. I know he wrote a ton of letters and correspondences, often signing them ‘Jackie Robinson.’ We would be mindful (of) that, in a particular source, that if calling him ‘Jackie’ seemed to be used in disrespect, it would be noted. I don’t recall anything we have or show where that would be the case, but that would also, for us, be part of the story to tell. Still, this is less of an issue than say with Roberto Clemente, where there was always a push and pull between him and the media (and baseball card companies) on changing his name.”

Robinson’s influence makes his birth name less recognizable than his nickname. Of course with Rachel at the forefront of JRF, she likely wanted to cater to the museum to the most people and used his better-known moniker. With his face plastered around the walkways going into the museum, I’m sure everyone could’ve figured it out if they honored his namesake cathedral as the Jack Robinson Museum.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here