Exclusive excerpt: ‘The Magicians of Mazda’ by Ashwin Sanghi – Times of India

The book is “492 pages of a thrilling adventure that blazes its way through America, Iran, Afghanistan, and Kashmir. It has always been my view that the greatest quality of a storyteller is to get the reader to turn the page. I have painstakingly attempted to do just that,” Sanghi had told us about his new novel earlier.

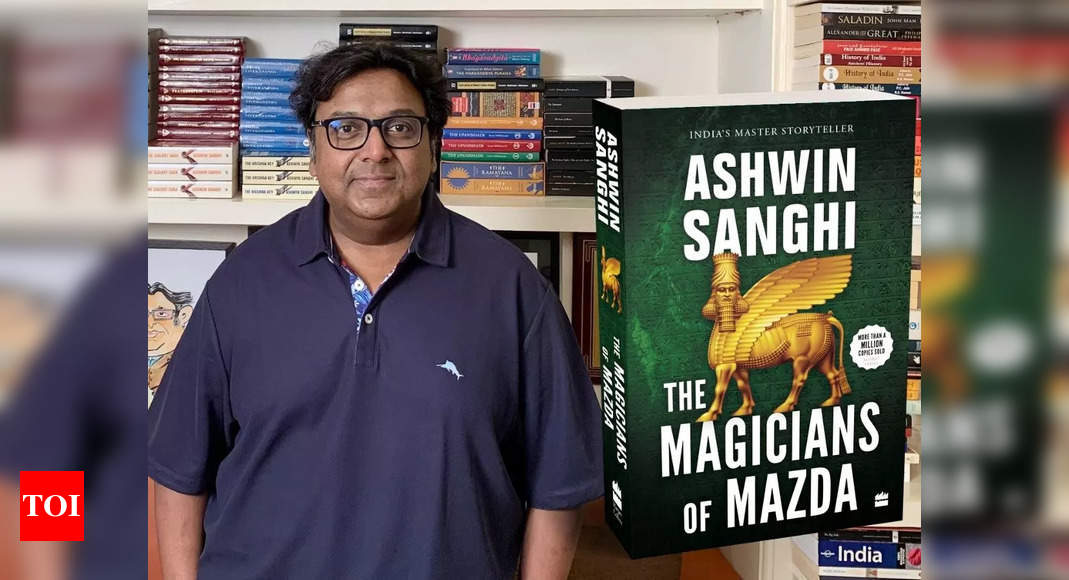

‘The Magicians of Mazda’ released on May 21, 2022. Here’s an exclusive excerpt from Sanghi’s new book ‘The Magicians of Mazda’, published with permission from HarperCollins India.

‘The Magicians of Mazda’ by Ashwin Sanghi

Less than forty kilometres by road from Surat is Navsari, a city inextricably linked to the history of Parsis in India. Parsis are the descendants of the Zoroastrians who fled from Iran to escape Muslim persecution and eventually settled in Gujarat around 720 ce. While many places are associated with this event, Navsari is the place that sheltered the Parsis for several centuries after they were driven out of Sanjan, the place where they had first landed in Gujarat. The birthplace of stalwarts such as Dadabhoy Naoroji, Jamsetji Tata and Jamshedji Jeejeebhoy, Navsari lies just thirteen kilometres away from Dandi where Mahatma Gandhi ended his famous Dandi March, in protest against the tax the British government levied on salt in India.

An aged visitor to Navsari, Pestonji Unwalla, ignored the city’s star attraction, the Zoroastrian Fire Temple, and made his way through the predominantly Parsi enclave of Tarota Bazar. Within Tarota Bazar lies the First Dastur Meherji Rana Library. Established in 1872, the library contains more than 45,000 printed books on different subjects, but is famous for its collection of about 630 rare manuscripts written in Avesta, Gujarati, Pahlavi, Pazend, Persian, Sanskrit and Urdu. The library is named after a Zoroastrian priest, Meherji Rana, who had visited Akbar’s court at the command of the Mughal emperor, who wanted to learn the key tenets of the Zoroastrian faith.

The white-bearded octogenarian entered the majestic blue and off-white structure and walked with a little difficulty up the flight of stairs leading to the main reading room. It was afternoon; the room was enveloped in a somnolent silence only punctuated by creaking ancient ceiling fans and the occasional cry of a hawker from the road below. The air was thick with the musty smell of old leather-bound covers, and portraits of the library’s patrons hung from the iron grille that ran around the perimeter of the mezzanine. The old man ignored the other patrons, who were leafing through newspapers and magazines in the reading room, and directly ascended a wrought-iron spiral staircase in one corner.

Somewhat winded, he arrived in an area filled with cupboards that were chockful of books. He then began the slow and laborious process of searching for the tome he sought. Thirsty after his climb, he licked his lips in anticipation of the thick gulkand ice cream that he would treat himself to after his task was completed.

The sheer scale of the collection would be daunting to most people, but Pestonji Unwalla had a secret resolve. His quest was for books listed in a 1923 catalogue by an Ervad Bamanji Nasarwanji Dhabar. From that catalogue, Unwalla had been able to eliminate the chaff and draw up a shortlist of the most likely candidates. He worked efficiently, scanning his list, searching for each book, running through its pages and then putting it back religiously in its place. One by one, his list became shorter. He scanned through the nineteenth-century illustrated and lithographed Shahnameh, the Persian epic by Firdausi. No luck. Outlines of Zend Grammar in Avestan. Nope. When he saw a 400-year-old copy of the Khordeh Avesta, his heart lifted briefly as he leafed through it, but it turned out to be one more false lead.

He was about to move on to another cupboard when he saw it. Kalila wa Dimna by Abdullah ibn al-Muqaffa. He picked it up and took it over to a reading table. Carefully turning the delicate, tissue-thin pages, he saw the handwritten scribble— and couldn’t believe he’d found what he had. It was just six lines, written in the Avestan language using the Pazend script. Strange to find Pazend jottings in an Arabic book. Unwalla quickly took a photograph using his mobile phone. Could it be Number 27? He looked at the words once again and mentally translated the text. He couldn’t be sure, but his instincts told him that he had found what he was looking for. He eagerly took more pictures.

Unwalla had not yet made a visit to Diu, a town on the coast of the island of the same name. Undoubtedly, Diu had archaeological treasures vested in the remains of two dakhmas and a fire temple, now protected by the Archaeological Survey of India. But Diu had been abandoned by the Parsis within nineteen years of their arrival there. Unwalla remained unconvinced that there would be any records or archives of value there. He had wisely realised that Navsari would be his best bet. And he now knew that his hunch had been a good one. Maybe Diu could be on the itinerary another day.

If he was right, then it would mean that centuries of history and tradition would be upended. It was possible that the guardians themselves were unaware of what lay beneath the religious symbolism. A key piece of their heritage had been entrusted to the safekeeping of an inner group, but it was something that belonged to Zoroastrians everywhere, not just the ones in India.

READ MORE: 8 books Warren Buffett wants everyone to read

For all the latest lifestyle News Click Here