Dame Alison Rose’s ousting is a sad end to a distinguished career with no obvious successor

In the end, Dame Alison Rose had no option to resign as chief executive of NatWest.

One of the oldest principles in banking is that banks must protect the privacy and confidentiality of their customers.

The only exceptions to that – laid out in a famous 1924 court case that created the so-called ‘Tournier principle’ – is where a bank feels it has a public or legal duty not to do so, where it is in its own interest not to do so, or where the client has themselves made a disclosure about their banking arrangements.

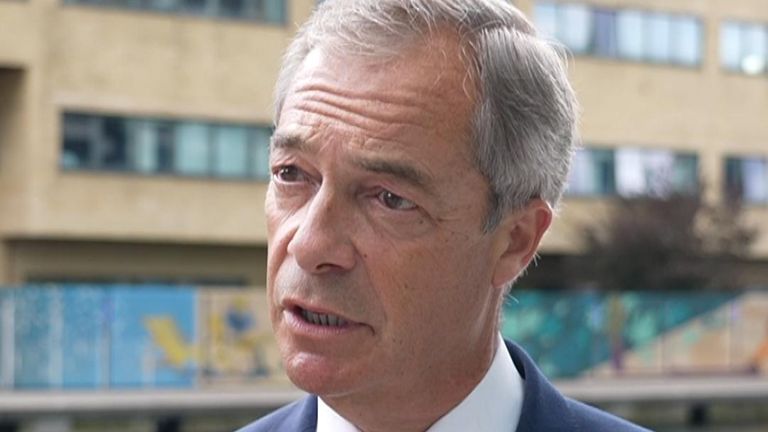

It was this last example that Dame Alison and the NatWest board explicitly reached for when, on Tuesday evening, she outed herself as the source of a BBC story concerning Nigel Farage‘s banking arrangements.

As Mr Farage had already gone public with news that he had been ‘debanked’ by Coutts, Dame Alison felt she had not disclosed anything which was not already in the public domain, which was spelled out in the statement released on her behalf by the bank.

She might just have ridden out the storm had that been the sole fact of the matter.

What was problematic for her, though, was that the decision to close Mr Farage’s Coutts account was not just a commercial one – the impression she left with the BBC – but also motivated, in part, by a very obvious dislike for Mr Farage by certain people within Coutts.

The documents put before the Coutts Wealth Reputational Risk Committee, made public by Mr Farage, referred to him, among other things, as a “disingenuous grifter”.

These were clearly unacceptable things for a bank to be saying about one of its customers.

Wider questions

The whole episode has raised questions about the acceptability of a bank closing a customer’s account because it is unhappy with their opinions – something the government, anxious to protect freedom of speech and opinion, wishes to stop.

Legislation to that effect is likely to be in the offing.

So what really cooked Dame Alison’s goose was that, even after the NatWest board had announced she had its support, were the briefings from Downing Street and Treasury indicating that the government – a 38.69% shareholder in NatWest – had misgivings about her staying on.

A sad end to a distinguished career

It is, though, a sad end to a distinguished career. Dame Alison, a NatWest lifer who joined the lender as a graduate trainee on leaving Durham University, had been chief executive since November 2019 and was regarded as having done a good job.

That is partly borne out by NatWest’s share price performance, which rose by nearly 18% during her tenure, outperforming those of sector peers Barclays, HSBC and Lloyds.

It is also borne out by NatWest’s financial performance.

Dame Alison, who had previously been deputy chief executive of NatWest Holdings and chief executive of the bank’s commercial and private banking division, built on the heavy lifting done by her predecessors, the City veteran Stephen Hester and the affable New Zealander Ross McEwan, to restore the bank’s financial stability following the debacle of the global financial crisis.

Significant achievements at NatWest

NatWest’s core tier one capital ratio – a measure of the capital held on its balance sheet – stood at 14.4% at the end of March this year.

That is a better figure than at any point since the financial crisis and was emblematic of a solid, well capitalised institution.

The bank has also restored profitability pretty dramatically.

Dame Alison made simplifying NatWest’s operations (for example by exiting its previously troublesome operations in the Republic of Ireland) and bringing down its cost base a priority.

And, broadly speaking, she succeeded in this task.

NatWest’s cost-income ratio (a measure of efficiency where the lower the figure is, the better) came down from 65.1% at the end of 2019, just after she started in the job, to 49.8% as at the end of March.

And that fed through to financial returns.

The bank’s return on equity (a measure of profitability where the higher the number is, the better) rose from just 9.4% at the end of 2019 to 19.8% at the end of March this year.

Now it can be argued that, with this latter metric, NatWest – as with its peers – has benefited from interest rates returning to a more normal level after 15 years of near-zero interest rates.

It is hard to disentangle from NatWest’s overall financial performance. But these are still significant achievements.

Aside from financial performance, Dame Alison also led NatWest with confidence during the pandemic, which pitched the UK into a recession.

NatWest and its peers – thanks partly to support measures put in place by the UK government – stood behind its small business customers, by and large, during the pandemic.

They received none of the criticism that, for example, the insurance sector did.

That track record is one reason why Sir Howard Davies, NatWest’s chairman, fought so doggedly to keep his chief executive in place.

Good banking chief executives now harder to come by

Another is that good banking chief executives are harder to come by than they were.

Yes, they are well paid, but these jobs bring with them a vast amount of pressure and, as Dame Alison has discovered, immense personal reputational risk.

The media, political and regulatory scrutiny is intense, the latter even more so since the financial crisis.

The vast scale and complexity of the technology operations in modern banks, too, brings an added hazard that banking chief executives did not have to worry about in the past.

A bank chief executive these days is only one serious IT failure or hacking incident away from losing their job as Paul Pester, the former chief executive of TSB, found to his cost in 2018.

That can deter many decent candidates from applying for such roles while, with UK lenders unable to offer the kind of salaries that, for example, banks pay in the United States, the pool of international talent available to fill the role is smaller than once it was.

A third reason why Sir Howard and the NatWest board fought to defend Dame Alison is that Sir Howard, a former Bank of England deputy governor and the first chief executive of the old Financial Services Authority, has himself said he will be stepping down by July of next year – by which time he will have served the maximum nine years during which a director is allowed to sit on a plc board.

No obvious successor

No quoted company, let alone one as systemically important as NatWest, wants to be looking for a new chairman and chief executive at the same time.

Yet that is now the invidious situation in which the bank now finds itself.

Unlike Dame Alison, who had been groomed as Mr McEwan’s successor for a number of years, NatWest does not appear to have been lining up an obvious successor for her.

Paul Thwaite, the former head of commercial and institutional banking and who has worked for the bank for more than 20 years, has been appointed for an initial year but was one of a number of internal candidates – others include Katie Murray, the chief financial officer and David Lindberg, the retail banking chief – who would have been in the frame to succeed Dame Alison had an appointment process been more drawn out.

Yet making Mr Thwaite an interim appointment is also not without risk.

HSBC was widely regarded as having mishandled the appointment of its current chief executive, Noel Quinn, when in 2020 it took more than seven months before his appointment was made permanent.

Some felt Mr Quinn was undermined as a result.

The likeable Mr Thwaite could do without similar speculation as his in-tray is already crowded.

While the UK is now widely expected to avoid a recession, these are still hard times to be running a bank, as was made clear by the results from Lloyds Banking Group this morning.

Lenders are having to set aside more money to cover doubtful loans and are going to come under pressure to support elements of their small business customer base.

House prices look set to fall and that will put some personal banking customers under pressure.

In the very short run, Mr Thwaite may also likely to have to grapple with investigations by the Information Commissioner and the Financial Conduct Authority into how information concerning Mr Farage’s banking arrangements came to be made public.

He may also come under pressure to downplay some of his predecessor’s initiatives.

Dame Alison was a champion of female entrepreneurship – one of her proudest legacies – but other initiatives, such as her decision to try to rein in NatWest’s exposure to fossil fuels and promoting diversity, antagonised those who deplore so-called ‘corporate wokery’ and think banks should stick to taking deposits and lending money.

It would be no surprise to see Mr Thwaite concentrating on those banking basics in coming months.

For all the latest business News Click Here