Bounty hunting and cheat chasing – the battle for Kenya’s conscience

Athletics’ extensive history of doping scandals is pockmarked by different nations: East Germany’s formalised system of the 1970s and 80s, Soviet field athletes during the late Cold War, Chinese long-distance runners that formed Ma’s Army in the 1990s, and Russia’s state-sponsored regime that so sullied London 2012, to name a few.

But the latest spate of positive drug tests to blight the sport comes from a country that, to the outside world, appeared to have married the perfect blend of nature and nurture to become a distance-running powerhouse.

Increasingly it is apparent that, for some, there was a more nefarious factor.

When, in May, 10km road world record holder Rhonex Kipruto became the latest high-profile Kenyan athlete provisionally suspended for suspected doping offences, there was a collective eye-roll across the sport. If his denials prove in vain and he is found guilty, the 23-year-old will be yet another name to add to the country’s roll of dishonour.

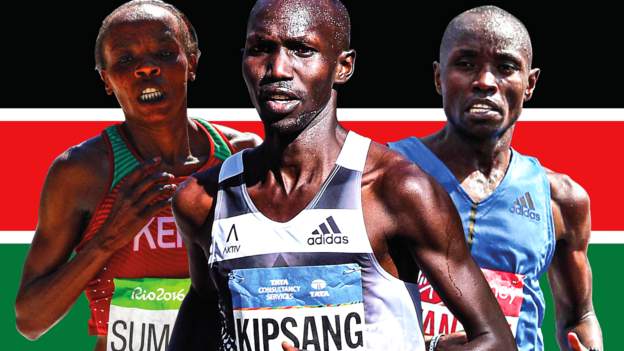

Former marathon world record holder Wilson Kipsang, former half marathon world record holder Abraham Kiptum, Rio 2016 Olympic marathon champion Jemima Sumgong, London Marathon winner Daniel Wanjiru, triple world 1500m champion Asbel Kiprop and his successor Elijah Manangoi are already part of a cast of high-profile Kenyan runners busted in recent years.

But as the number swells and the external clamour to kick Kenya out of athletics grows, the man tasked with cleaning up the sport has an alarming message, born of hope.

“Everyone has to be prepared because there are going to be a lot more doping cases in Kenya in the next few months and years,” states Brett Clothier, head of the Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), the independent body created five years ago to combat the sport’s doping problem.

“I’m trying to tell everyone: ‘Don’t be surprised. Don’t be shocked’. This is what needs to happen to get this under control. It’s now or never.”

Big changes are underway in a country where supreme talent combines with unrivalled opportunities to create a doping minefield. And, as Clothier predicts, that list of cheats is only going to grow.

Four years ago, Clothier stood at the front of a conference room in the Chinese city of Lanzhou. His audience included most of the road-racing industry’s leading players. A man entirely undaunted in his quest for the truth, Clothier knew the best way to provoke a response was searing honesty. So he loaded a slide on to the screen.

“The current situation is unsustainable and the road-running industry is approaching a doping scandal comparable to the worst in sport,” read the words in big, bold font.

Beneath it were some haunting numbers.

In the previous year’s 50 Gold Label races – the world’s biggest road races below the Boston, London, New York, Chicago, Berlin and Tokyo marathons – 76% of winners had not been drug tested out of competition prior to their victory.

In fact, almost half of men and women’s podiums consisted entirely of athletes who had yet to be tested out of competition.

Clothier’s message was simple: if those involved in road racing wanted to restore any semblance of belief in their product, they would need to dip into their pockets and stump up some cash to dramatically increase anti-doping processes.

The epicentre was evident. About 80% of untested athletes making the podium at those lucrative, high-profile races hailed from the distance-running superpowers of Kenya and Ethiopia.

“What we’re seeing in the marathon – especially in Kenya and Ethiopia – is literally hundreds of athletes, who are totally outside of the net, highly motivated to dope because they earn good money,” says Clothier.

“It has been a wild west, and you can’t even blame the Kenya anti-doping system that much because no other country in the world has that concentration of athletes going after such big prizes.”

In athletics terms, Kenya is something of a perfect storm. A natural affinity for long-distance running for much of the population combines with a nationwide passion for the sport to create an abundance of talent unmatched worldwide, beyond perhaps its Ethiopian neighbours.

Widespread poverty – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ranks Kenya 147th globally for gross domestic product (GDP) per capita – makes the financial incentives to succeed even greater.

While the London Marathon offers a hefty £42,000 to its winners and the prize pot at other major marathons stretches to six figures, lower-profile races like the Nagoya Women’s Marathon ($250,000, roughly equivalent to £191,000), Seoul Marathon ($100,000, or £76,000) and Dubai Marathon ($80,000, or £61,000) give large sums to those who triumph.

Clothier says it is no wonder drugs have proliferated in the country.

“Road running is the most lucrative part of athletics,” he says. “There’s prize money, appearance fees, and hundreds and hundreds of races worldwide for people to go and earn money.

“So what you have in Kenya is a huge professional class of runners who can earn a really good living, especially by Kenyan standards, running on the road. That creates a really large illicit market for performance-enhancing substances.

“When you have this illicit market, you have the opportunity for people to financially benefit from doping, and people who have the financial opportunity to sell performance-enhancing drugs. What we see is a classic, uncoordinated illicit drugs market driven by money.

“These factors are unique to Kenya. Unlike in many countries where you have a centralised national team, these professional runners don’t represent Kenya at the Olympics or major events. In fact, they are many, many rungs away from that level.

“The 100th-ranked Kenyan in the marathon can go around the world earning really good money as a professional runner. That brings up a lot of challenges for the domestic anti-doping programme, because in many other countries the hundredth-ranked long jumper, for example, has to work in a supermarket, hasn’t got a huge incentive to dope and we don’t expect the anti-doping agency to be testing them.”

Given Kenya’s unrivalled distance-running prowess – last year was the first time the country finished outside the top three of a World Championships medal table since 2007 – it is easy to forget what a largely recent phenomenon it is.

Only one Kenyan male – Douglas Wakiihuri – triumphed in the first 23 years of the London Marathon up to 2004, a year after Paul Tergat had become the first Kenyan to hold the men’s marathon world record. Neither man failed a drugs test throughout their careers, but their success sparked something back home.

“After the era of Paul Tergat something went wild,” says Kenyan sports journalist Evelyn Watta. “It was when the Kenyan media opened up.

“Before that we only had one or two different broadcasters, but now we had everyone following athletics so everyone became aware of these runners becoming famous and rich.

“They saw you can actually live off running so everyone started aspiring to be runners.

“There is a saying that every other day a Kenyan runner is born. It has meant that it is so hard to stay at the top. That’s where doping comes in.”

Understandably, for a country experiencing such rapid global success, Kenya’s anti-doping infrastructure was largely left behind.

The Anti-Doping Agency of Kenya (Adak) was only created in 2016, after the country had narrowly avoided a ban from the Rio Olympics for a series of doping breaches and corruption allegations.

In 2018 a World-Anti Doping Agency (Wada) report titled ‘Doping In Kenya’ found 138 Kenyan athletes had tested positive for prohibited substances between 2004 and 2018, but a lowly 14% of those were caught in an out-of-competition test.

“For a very long time, Kenyans were not tested at home,” says Watta.

Gunter Younger, the Wada report’s lead author and director of intelligence and investigations, said the financial attractions for doping are paramount.

“For most of the athletes we talked to, income was the biggest factor, not only for their family but sometimes their whole tribe,” he says. “Most of the athletes were in a sub-elite group so for them, winning 5,000 euros (£4,292) ensured they could survive for a year.

“There’s a big shame for them to admit they have cheated, but they take the risk to get some money. They have little education and don’t know what the drugs are or the repercussions for their body – for them it was more important to run.”

That Wada report found much of the doping in Kenya was “unsophisticated and uncoordinated”. But Clothier says the past five years have seen an increase in sophistication and “organised criminal activity”.

Indeed, when investigating the doping case of middle-distance runner Eglay Nalyanya this year, the AIU uncovered a “pattern of behaviour” in the forged documents that formed part of her fraudulent defence and those used by fellow Kenyan athlete Betty Lempus.

Attempting to cover up their drug taking, both women submitted letters from non-existent doctors for intramuscular injections that never took place.

This led the tribunal to conclude that “elite Kenyan athletes are being assisted by a person or persons, including someone with considerable medical knowledge, to commit what amounts to criminal conduct involving frauds on the AIU”. Nalyanya and Lempus were subsequently banned for eight and five years respectively.

It was only the latest example of Kenyan drug cheats lying to cover their tracks.

When questioned about the presence of EPO in a 2014 drug test, three-time Boston Marathon champion Rita Jeptoo produced falsified medical records which were the “culminating peak in an overall strategy” of cover-up and concealment, according to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (Cas).

Rio Olympics marathon champion Sumgong produced similarly altered medical records following an EPO positive, and when Kipsang committed four whereabouts failures in 2018 and 2019, he provided false witness testimony and used a fake photograph of an overturned lorry to try to justify a missed test.

Their actions are indicative of a wider malaise in Kenyan society, says Watta: “The problem of doping exposes the Kenyan culture of corruption and impunity. We do bad things and somehow we buy our way out.

“I can drive a faulty car, but if the policeman stops me I will bribe my way out. It’s a national culture that is now being fought, but it’s deeply ingrained and it’s gone across sports as well.”

Clothier says the country’s corruption culture is “absolutely a concern”, but believes the increasingly organised criminal activity, fuelled by “exploiters” looking to benefit financially from athletes, is a greater worry.

“If a good runner emerges they have dollar signs flashing all around them,” he says. “Exploiters – whether it’s medical professionals, pharmacists, fixers, whoever – will offer them drugs.

“None of the athletes in Kenya need to go far and wide to search out drugs. People come to them offering drugs. It’s a financial opportunity. So there are networks of people who approach athletes.”

Clothier’s alarmist approach in that 2019 road-racing industry presentation – warning of “a doping scandal comparable to the worst in sport” – had the desired effect.

As well as road-race organisers and athlete representatives, shoe companies Asics, Adidas and Nike all contributed to the creation of the Road Running Integrity Programme in 2020, which pledged an extra $3m (£2.39m) to fund out-of-competition testing of the leading 300 long-distance athletes regularly taking part in Gold Label races.

With unfortunate timing, the Covid pandemic meant it was forced to operate at a much-reduced level for its first three years, with a testing pool of about 80 runners. As of this year it is at full capacity, with slightly more than 150 men and 150 women – of which about 40% are from Kenya and Ethiopia respectively – now tracked year-round.

Yet, it has become increasingly apparent that targeting the country’s elite is insufficient.

Kenya’s unique problem is the sheer abundance of talent that sits below global level.

“In Kenya, there is a huge pyramid of top-class athletes,” explains Clothier. “The difference in ability, in that pyramid, between the top and those below is not very much because of the depth of their talent.

“In the past we have been testing the top of that pyramid, but the bottom ones have not been subject to out-of-competition testing.

“That pyramid is hundreds, or even thousands, of athletes.

“So even though we are controlling the ones at the top very well and are capable of catching cheaters, because of the pressure from the athletes below, who aren’t being tested out of competition, the athletes at the top are taking risks and there is pressure to stay on top.”

That is all about to change. In late 2022, the Kenyan government pledged to increase funding for anti-doping by $5m (£4m) a year for the next five years.

The Kenyan anti-doping pool – the tier of athletes underneath those in the Road Running Integrity Programme – has increased from 38 in 2022 to more than 300, while testing at Kenya’s national championships and trials for August’s World Championships has increased sevenfold in 12 months.

“This money can be a real game-changer,” says Clothier. “No other national anti-doping agency is at that level of testing in our sport.”

Ever since he became the first head of a governing body to kick Russia out of their sport in 2015, World Athletics president Lord Coe has shown himself to be unafraid to weed out those who sully athletics.

But while the Russian state-sponsored systematic doping regime was met with the ‘stick’, some count Kenya fortunate to be offered a ‘carrot’ and the chance to stay at the sport’s top table.

Only Russia and India – whose specific problems almost entirely involve athletes below international level – have more athletes currently suspended for doping offences than Kenya’s 64. Coe insists the effort and expense in Kenya is justified.

“I couldn’t be asking more at this moment of the Kenyan federation,” said Coe. “The Kenyan federation is really doing everything it possibly can to strengthen its systems.

“We’re spending quite a chunk of money. For instance, it was through World Athletics and the Athletics Integrity Unit that we now have a blood-testing facility in Nairobi [launched in 2018]. We also are spending quite a lot of cash on education programmes, teaching young Kenyans coming through.”

The AIU is going further, helping to guide how the Kenyan government’s newly pledged money should be spent with a senior AIU official moving on secondment to Adak for two years.

“Kenya is very different from, for example, Russia, which had a centralised system,” explains Clothier.

“In Russia, we had one case related to Danil Lysenko [world high jump silver medallist] in 2019 that included the federation president, CEO, a board member and the anti-doping manager all conspiring with the athlete to cover up an anti-doping rule violation.

“To the contrary, in Kenya we have Adak and Athletics Kenya helping us uncover cases.

“There is a lot of doping happening, but the federation, anti-doping authorities and government are doing their utmost to try to fix the problem.”

The result, of course, means more failed drug tests. A paradox of all anti-doping agencies is that a lack of positive tests is not necessarily cause for celebration.

So while others might despair at the steady stream of Kenyan runners caught cheating, Clothier remains unequivocal that it represents success.

“No-one thinks that there was less doping in Kenya five years ago,” he says. “It’s just now we’re catching people and trying to fix things.

“The first step is uncovering what’s happening. That has created a lot of drama, but it has got everyone to take it seriously. It’s a really difficult task, but if ever there is going to be serious improvement in anti-doping in Kenya it’s now.

“There’s the money there and there’s a proper process for spending it. That all begins with a big step up in testing from this summer. It’s exciting because there’s the potential for real change.”

So take heed. The hefty list of Kenyan dopers is only going to get longer and things will look worse as they improve; it is short-term pain for long-term gain.

For all the latest world News Click Here