Behind ‘GotaGoGama’: How The Economic Crisis in Sri Lanka Is Unfurling Misery

The family was all set to have breakfast. In what appeared to be an oft-repeated line, one of the children asked if they were about to “break the fast”. The worn-out joke was allowed to sink without a ripple.

As the elders stepped out to look for work, the adolescents stepped up to manage the kids. For 17-year-old Imdad, the responsibility was a bit too much. He popped paracetamol as he massaged his delicate knee while appearing to ignore the hunger pangs. On most mornings, this is how Imdad is, at least since the crippling crisis gripped Sri Lanka. His knee was all set for a procedure that would relieve him of hours of misery every day but the plans got swept away in an economic sinkhole, sucking savings and livelihood into its swirling depths.

Imdad’s ill luck is a common theme in Lanka. In late March, he was admitted to a government-run hospital in Colombo a few days ahead of his surgery. Just a day before the procedure, he was told he may have to wait a little longer. For a teenager impatient to get back to his waywardly youthful bunch of friends, an “économic crisis” made no more sense than economics. He just understood one thing: the hospital did not have medicines. To him, Sri Lanka has always been an unpredictable land, brimming with earthly beauty one day and seeming to be a cursed land of strife the other. Long before, he had given up trying to understand his motherland’s deep troubles. ” They gave me many reasons for the delay in surgery but we all know the truth. They didn’t have essential medical supplies for the surgery. I was waiting for the surgery as I thought the pain and the turmoil I went through would come to an end. I have to bear the pain,” he said.

Imdad is not alone but part of a legion. Several thousands in the middle classes have had to suffer in the throes of the island nation’s economic crisis. The Gotabaya Rajapaksa-led government has vigorously fought off political opposition to hold on to power, but angry protests led by the Sinhalese working classes, students, lawyers and the educated communities have forced a definitive moment of truth on the ruling clan. For so long, establishing a thriving Sinhala-Buddhist government was seen as an end in itself. An epochal shift is underway, led by a demand for a progressive government that offers jobs, policy stability and economic development.

Not quite like Imdad, Sri Lanka nurses an innumerable number of silent sufferers faced with grave danger. Sixty-two-year-old Vena Alvis is recovering after heart surgery. Her mobility has been greatly impacted in the wake of her procedure. Walking, while leaning on a staff, she barely manages ten steps at a time. Her journey through the crisis has been rough. “Sometimes I go to the clinic, there is no medicine. If I go to the pharmacy, there is no medicine. Sometimes, I cannot breathe without medicine. Sometimes, I cannot even take 10 steps if I skip the medicine. Due to my poor health, my husband has to run around everywhere for days to find the drugs required for me,” she said. “It is that bad for us here.” For cancer survivors too, the struggle has been getting worse by the day. Thirty-eight-year-old cancer survivor Irshan has had to depend on Indian supplies after his medicine stash at home dried off. His doctors make urgent calls to global suppliers to ship the medicines. He is taking it one day at a time.

Official authorities say an essential medicine list is doing the rounds. “There are certain medicines used only during surgeries. There are drugs used during heart attacks, drugs required for cancer patients…there is a list of 14 drugs that are required immediately and there is an expanded list,” said Professor Indika Karunathilake, secretary general, Asia Pacific Academic Consortium for Public. Health.

Stepping back into the past—decades at a time

The morning broke in a sort of whine in Sri Lanka. The sun filtered in through the thin curtains of Sumangala’s modest home in Colombo. Even before tea, her husband had hobbled off for his daily chore in the morning—collecting firewood. While the effort was exacting and the cooking would take hours instead of the gas stove’s half-hour, Sumangala is, strangely, not complaining. It’s been years since she cooked using firewood. It brought back memories of her mother’s cooking and living in cramped quarters outside of the capital where the houses were smaller but the fields where they played were much larger.

“It used to take me just 30 minutes to cook. The only downside is that we cannot have an elaborate meal with firewood. Every day, there’s rice, sambhar, and a few other items. With many people going the firewood way, buying them has become a challenge too. My husband has to run around to buy these,” 44-year-old Sumangala said.

Firewood may evoke nostalgia for people like Sumangala but for those in poor health, such as Alvis, it is turning out to be a nightmare. “I am not allowed to blow the firewood while the food is getting cooked. What can I do? I don’t have a choice. I have to cook for myself and my husband. My husband panics a lot and keeps trying to find a gas stove to ensure I don’t fall sick. However, the crisis is only worsening. We don’t have much left here,” Alvis added.

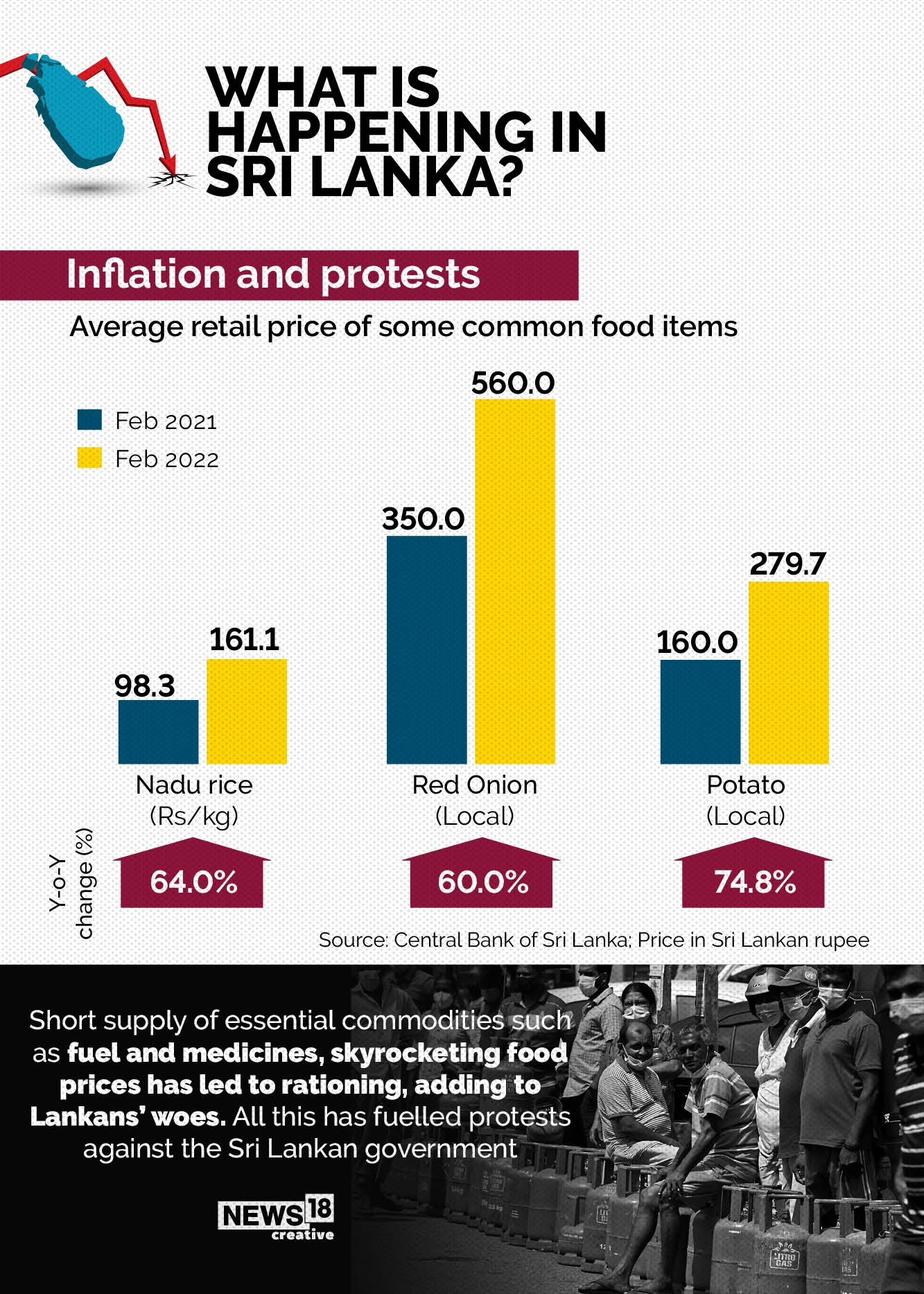

Skyrocketing prices of essentials have become a constant feature in beleaguered Sri Lanka now. From milk to rice to fuel to medicines, severe short supply has driven up prices. In Colombo, ordinary drug prices have shot up by 39%, say pharmacy owners. “Our food expenses alone cost Rs 60,000. My husband was the sole breadwinner of the family. But with growing inflation, I also started working. If both of us don’t work, we won’t be able to provide food for our two kids. We are daily wage labourers and we struggle to make ends meet,” said 30-year-old Krishnakumari, a resident of the capital city.

Price inflation has had an acute impact on children. Parents are trying to wean children away from milk at ages earlier than before; some have shifted to black tea or coffee for their children. “My son keeps asking me for milk. There is no milk available anywhere. Poor boy. I lie to him that after his cough stops, I will give him milk. I keep giving excuses to my son. What else can I do?,” Krishnakumari added.

Strangely enough, children have also proven resilient to the crisis. They adapt quicker than anticipated. “I like milk very much. My mom tells me there is no milk and gives me tea. Now, I am used to black tea,” Krishnakumari’s six-year-old son told CNN-News 18.

The fuel shortage, which was one of the first clear signs that Sri Lanka was slipping into a crisis, refused to abate. At the time of writing this story, petrol prices hovered around Rs 303 a litre. Most pumps have sported a ‘No Supply’ sign for over a week now. The ones operational have queues stretching over a kilometre. Any bunk open for supply makes for instant news in the locality. Sajith, a car driver, has never struggled for fuel in his 30-year career. The Covid-19 crisis was a rude shock to his business, after lockdowns and softening demand took the wind off his sails: “Now, as things were returning to normalcy everywhere, just when we thought tourism would flourish, the crisis has impacted our lives yet again.”

Strangely, there is an influx of tourists looking to leverage the favourable currency situation for visitors. Many resorts and luxury theme parks are getting patrons from Europe and other parts of Asia, but the incoming revenue does not go beyond the hotel owners, thanks to the fuel shortage. “When we manage to find tourists, we sometimes run out of fuel. I waited for four hours in the queue only to be told there was no diesel. This has been happening for over two months. If the situation continues, we won’t be able to find vehicles on the road in a month or two,” Sajith said.

#GotaGoGama: A protest site, as we live and breathe

The Rajapaksa clan, a powerful political family, has had to face immense pushback from a political constituency they have nurtured for decades: the Sinhala majority. The protests rocking the Galle Sea Face in Colombo are populated by Sinhalese students and working classes across the majority ethnic community.

An 86-year old grandmother is walking through the protesting crowds, happy to be alive to be witnessing what appears to be a true “Sri Lankan expression”. A 19-year-old sprightly youngster brandishes a 12-socket spike buster to charge up smartphones. An elderly man goes around handing out black tea in paper cups. The camaraderie is unmissable.

Nevertheless, the undercurrent is a sense of anger as youths directly express their ire at the political establishment for mismanaging finances. Thousands are on the streets every day, raising slogans and carrying placards that flash “Go Home Gota” prominently. Protesters have “occupied” the Galle Face area for days now. Tents are pitched around the neighbourhood, hosting angry protests whose energy is matched only by the swelling numbers. From children and youngsters to the middle-aged and elderly, the sentiment of protest has united economic classes to force the Rajapaksas to step down.

For a political family that has enjoyed unequivocal support for years of ethnic strife involving the Northern Tamils, the crisis faced by the Rajapaksas is truly a total reversal of fortunes.

“It is a historic movement in Sri Lanka,” businessperson Gayantha told CNN-News18.

Across the Lankan protest sites, Sinhalese say they are happy to see the “Go Home Gota” sentiment has cut through barriers. “We have never seen anything like this before. People representing all religions and all ethnic groups have united under one banner, to force the corrupt regime led by the Rajapaksas to quit immediately. They are angry and they want to change the system,” Gayantha said.

Businesspersons have for long tried to position Sri Lanka as a manufacturing destination but they’ve had little luck. The ethnic strife through the late 1990s and noughties have made sure the land is constantly on the boil. With a period of relative peace after the end of the armed conflict involving Sri Lankan Tamils, business has made a timid reentry. But all that has come to a screeching halt after the crisis. “Our apparel business has had 70% of our orders from international countries. We have lost a huge chunk of our clients. Our factories are non-operational for over two months because of power cuts. We have lost our credibility and trust among our clients. It has a long-lasting effect on people like me,” said Yusuf, a textile exporter.

The Tamil question

It appears as though the Sri Lankan crisis is set to escalate in the coming weeks as the Rajapaksas hold on steadfastly to power. A long line of police buses are just cruising in at the Galle Sea Face protest site, and helmeted policemen are looking on stonily as youngsters belt out hard-hitting sloganeering directed at the government.

While the Sinhalese protesters claim that the crisis has erased ethnic discord that has marked Sri Lanka since the early 1980s, some Tamils have been vocally debunking this assertion. They are severely impacted by the economic crisis just like the Sinhalese and other communities but the Tamils have largely remained muted. There has been a steady stream of economic refugees who have reached Tamil Nadu’s Dhanushkodi since the crisis began. While the economic impact has been no less on the Tamils, their protest sentiment has not been so directionally unified as the protesting Sinhalese in the Galle Sea Face, Colombo.

Some of them have taken to Twitter. The Sri Lankan Tamil intelligentsia has been quick to point out that the Tamil struggle for equality in the island nation predates the Galle Sea Face protests by years, and that it would be improper to compare or gloss over the pain caused to the ethnic minority. Tamils have said the protests against corruption, nepotism and the collective inaction that has run the country to the ground should not stop with sending Gotabaya Rajapaksa home. “Tamil families have disappeared from the North-East and there have been protests continuously for five years now. Once more, their struggle gets ignored by Sri Lanka,” said Dr Thusiyan Nandakumar, who is also on the editorial board of the news site Tamil Guardian, from his verified Twitter handle.

Sociologically, say political observers, it remains to be seen if Sri Lanka’s current crisis can have a sweeping power to close old wounds from the multi-layered history, which goes beyond the historic strife between the Sinhalese majority and the Tamils. The history of the plantation workers, the violence against the Muslims and the terror regimes wreaked by Tamil militants on their own community are still relevant in how Sri Lanka evolves. As the island nation sleeps and wakes another day, its multi-cultural history gets another layer to internalise and hold out for the future.

Read all the Latest News , Breaking News and IPL 2022 Live Updates here.

For all the latest world News Click Here