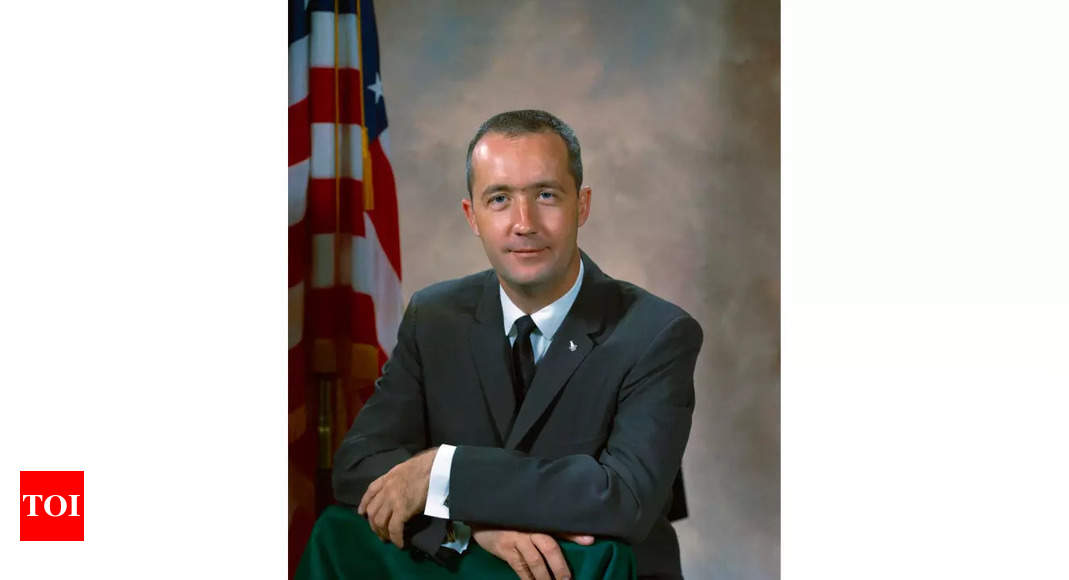

Astronaut James McDivitt, Apollo 9 commander, dies at 93 – Times of India

WASHINGTON: James A McDivitt, who commanded the Apollo 9 mission testing the first complete set of equipment to go to the moon, has died. He was 93.

McDivitt was also the commander of 1965’s Gemini 4 mission, where his best friend and colleague Ed White made the first US spacewalk. His photographs of White during the spacewalk became iconic images.

He passed on a chance to land on the moon and instead became the space agency’s program manager for five Apollo missions after the Apollo 11 moon landing.

McDivitt died on Thursday in Tucson, Arizona, Nasa said on Monday.

In his first flight in 1965, McDivitt reported seeing “something out there” about the shape of a beer can flying outside his Gemini spaceship. People called it a UFO and McDivitt would later joke that he became “a world-renowned UFO expert.” Years later he figured it was just a reflection of bolts in the window.

Apollo 9, which orbited Earth and didn’t go further, was one of the lesser remembered space missions of Nasa’s program. In a 1999 oral history, McDivitt said it didn’t bother him that it was overlooked, “I could see why they would, you know, it didn’t land on the moon. And so it’s hardly part of Apollo. But the lunar module was key to the whole program.”

Flying with Apollo 9 crewmates Rusty Schweickart and David Scott, McDivitt’s mission was the first in-space test of the lightweight lunar lander, nicknamed Spider. Their goal was to see if people could live in it, if it could dock in orbit and — something that became crucial in the Apollo 13 crisis — if the lunar module’s engines could control the stack of spacecraft, which included the command module Gumdrop.

Early in training, McDivitt was not impressed with how flimsy the lunar module seemed, “I looked at Rusty and he looked at me, and we said, Oh my God! We’re actually going to fly something like this?’ So it was really chintzy, it was like cellophane and tin foil put together with Scotch tape and staples!”

Unlike many of his fellow astronauts, McDivitt didn’t yearn to fly from childhood. He was just good at it.

McDivitt didn’t have money for college growing up in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He worked for a year before going to junior college. When he joined the Air Force at 20, soon after the Korean War broke out, he had never been on an airplane. He was accepted for pilot training before he had ever been off the ground.

“Fortunately, I liked it,” he later recalled.

McDivitt flew 145 combat missions in Korea and came back to Michigan where he graduated from the University of Michigan with an aeronautical engineering degree. He later was one of the elite test pilots at Edwards Air Force Base and became the first student in the Air Force’s Aerospace Research Pilot School. The military was working on its own later-abandoned human space missions.

In 1962, Nasa chose McDivitt to be part of its second class of astronauts, often called the “New Nine,” joining Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and others.

McDivitt was picked to command the second two-man Gemini mission, along with White. The four-day mission in 1965 circled the globe 66 times.

Apollo 9’s shakedown flight lasted 10 days in March 1969 — four months before the moon landing — and was relatively trouble free and uneventful.

“After I flew Apollo 9 it was apparent to me that I wasn’t going to be the first guy to land on the moon, which was important to me,” McDivitt recalled in 1999. “And being the second or third guy wasn’t that important to me.”

So McDivitt went into management, first of the Apollo lunar lander, then for the Houston part of the entire program.

McDivitt left Nasa and the Air Force in 1972 for a series of private industry jobs, including president of the railcar division at Pullman Inc. and a senior position at aerospace firm Rockwell International. He retired from the military with the rank of brigadier general.

McDivitt was also the commander of 1965’s Gemini 4 mission, where his best friend and colleague Ed White made the first US spacewalk. His photographs of White during the spacewalk became iconic images.

He passed on a chance to land on the moon and instead became the space agency’s program manager for five Apollo missions after the Apollo 11 moon landing.

McDivitt died on Thursday in Tucson, Arizona, Nasa said on Monday.

In his first flight in 1965, McDivitt reported seeing “something out there” about the shape of a beer can flying outside his Gemini spaceship. People called it a UFO and McDivitt would later joke that he became “a world-renowned UFO expert.” Years later he figured it was just a reflection of bolts in the window.

Apollo 9, which orbited Earth and didn’t go further, was one of the lesser remembered space missions of Nasa’s program. In a 1999 oral history, McDivitt said it didn’t bother him that it was overlooked, “I could see why they would, you know, it didn’t land on the moon. And so it’s hardly part of Apollo. But the lunar module was key to the whole program.”

Flying with Apollo 9 crewmates Rusty Schweickart and David Scott, McDivitt’s mission was the first in-space test of the lightweight lunar lander, nicknamed Spider. Their goal was to see if people could live in it, if it could dock in orbit and — something that became crucial in the Apollo 13 crisis — if the lunar module’s engines could control the stack of spacecraft, which included the command module Gumdrop.

Early in training, McDivitt was not impressed with how flimsy the lunar module seemed, “I looked at Rusty and he looked at me, and we said, Oh my God! We’re actually going to fly something like this?’ So it was really chintzy, it was like cellophane and tin foil put together with Scotch tape and staples!”

Unlike many of his fellow astronauts, McDivitt didn’t yearn to fly from childhood. He was just good at it.

McDivitt didn’t have money for college growing up in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He worked for a year before going to junior college. When he joined the Air Force at 20, soon after the Korean War broke out, he had never been on an airplane. He was accepted for pilot training before he had ever been off the ground.

“Fortunately, I liked it,” he later recalled.

McDivitt flew 145 combat missions in Korea and came back to Michigan where he graduated from the University of Michigan with an aeronautical engineering degree. He later was one of the elite test pilots at Edwards Air Force Base and became the first student in the Air Force’s Aerospace Research Pilot School. The military was working on its own later-abandoned human space missions.

In 1962, Nasa chose McDivitt to be part of its second class of astronauts, often called the “New Nine,” joining Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and others.

McDivitt was picked to command the second two-man Gemini mission, along with White. The four-day mission in 1965 circled the globe 66 times.

Apollo 9’s shakedown flight lasted 10 days in March 1969 — four months before the moon landing — and was relatively trouble free and uneventful.

“After I flew Apollo 9 it was apparent to me that I wasn’t going to be the first guy to land on the moon, which was important to me,” McDivitt recalled in 1999. “And being the second or third guy wasn’t that important to me.”

So McDivitt went into management, first of the Apollo lunar lander, then for the Houston part of the entire program.

McDivitt left Nasa and the Air Force in 1972 for a series of private industry jobs, including president of the railcar division at Pullman Inc. and a senior position at aerospace firm Rockwell International. He retired from the military with the rank of brigadier general.

For all the latest world News Click Here

Denial of responsibility! TechAI is an automatic aggregator around the global media. All the content are available free on Internet. We have just arranged it in one platform for educational purpose only. In each content, the hyperlink to the primary source is specified. All trademarks belong to their rightful owners, all materials to their authors. If you are the owner of the content and do not want us to publish your materials on our website, please contact us by email – [email protected]. The content will be deleted within 24 hours.