A level playing field: The past, present and future of women’s football

Gentlemen Only; Ladies Forbidden.

The popular falsehood that this phrase is the origin behind the term “golf” is an insidious one, as there is nothing about hitting a ball with a club that has ever been exclusively male.

The English golf comes from the Scottish goulf, which likely came from the Dutch kolf, the word for a “bat” or “club” and the game of the same name.

The modern, Scottish iteration of the sport has been exclusive to class, which is unsurprising considering how the sport is currently played. For a game that requires countless balls, pristine lawns and enough leisure time to afford the activity, golf has long been reserved for the wealthy. It was also reserved for men.

Yet, Mary Queen of Scots used to play.

In the 1500s, Mary was a pioneer of Scottish golf, introducing caddies and establishing the St. Andrews Links. The athletic noble didn’t shy away from sports traditionally reserved for aristocratic men such as hunting, hawking and archery, and she played rounds of golf with her ladies-in-waiting. At the time, Scottish historian George Buchanan wrote that Mary was playing “sports that were clearly unsuitable for women.”

The notion that the nature of sports — activities that often require physical strength and strategy — inherently reinforces masculinity and undermines femininity seems impervious to time and geography. Today, following a month dedicated to remembering women’s history, during the semicentennial of Title IX, the sports world is forced to reckon with the absurd lack of progress when it comes to gender equity in sports.

The story of the “Mother of Golf”, like many female athletes that have lived and died between eras, is disconnected because a direct line of tradition did not continue. Women separated by time are forced to pioneer movements over and over again until enough inertia pushes society forward. The golf course Queen Mary founded didn’t have a Ladies Club until 1867. American football is not so different.

There is an egregious omission from the collective American sports consciousness: women play football, and they’ve been doing it for nearly a century. Rather, women have been fighting to play football for nearly a century, but they’ve been systemically prevented from doing so in virtually every regard. When women wanted to play, park permits were revoked, then it stopped. Then it was viewed as a nonsensical gimmick. Then women struggled to gain visibility for decades. Today, a girl’s right to play football still isn’t protected by Title IX, allowing schools to refuse access to the sport indefinitely.

Women played in the 1930s, and the 1970s, and the 2000s, but they don’t share the neat, linear tradition that NFL alumni enjoyed in their recent NFL 100 centennial celebration. Football is a brutal sport, but women have paid a higher price because gender normativity doesn’t like to see women clash in pads and helmets.

History informs the present, and the present moment points toward a real future for female football players. Former football players like Jennifer King, Lori Locust, and Katie Sowers have made NFL coaching history, but their roots are in women’s tackle leagues like the Women’s Football Alliance (WFA) and the Independent Women’s Football League (IWFL). Before Super Bowl LVI, Team Milk launched their “Football Is Football” campaign featuring Jo Overstreet, Adrienne Smith, Jona Xiao and Lois Cook. UnderArmour recently partnered with Sam Gordon, the 19-year-old athlete/activist who created the Utah Girls Tackle Football League so hundreds of Utah girls could play. And one day soon, iconic sportscaster Erin Andrews would love to see her WEAR brand, made by women for women, sport the names of football teams starring women.

What all of these women prove is that women are not simply fans of football: women play, and they have played a harder game than anyone can imagine.

Part I: Girls Can Play

“Women desisting from play after community outrage is a pattern that repeats itself continuously throughout women’s football history.” Hail Mary, page 42

American football is, by nature, a violent sport.

Its origins are informal, being traced back to Greek and medieval European games played between neighboring villagers hauling a pig bladder across town. This was known as “mob football”, which included an unnumbered mass of people hurtling an inflated ball about in chaos.

This was the genesis for the modern games of soccer and rugby, which were codified in English public schools in the 19th century. Later in that century, American football began to take shape in Ivy League universities. Harvard, one of America’s oldest institutions, began a tradition in 1827 called “Bloody Monday” in which a game of mob football was played between freshman and sophomore classes. Bloody Monday was, in fact, too bloody, with police and university officials agreeing the ritualistic game had to end in 1860. The intolerance for football spread to Yale, where the game was banned there the same year.

Football’s origins are essential to understanding why the sport has excluded women for over a century.

Soccer has its own history of shutting out women in the UK, where it was once more popular than men’s soccer. Women’s rugby is also disproportionately underrepresented compared to men’s, but both of these sports now have women competing at the Olympics and in international competitions. Though soccer, rugby and American football were all derived from a mob-style game that was civilized through codification, American football took a unique path that retained a great deal of brutality.

Soccer is physical, but there’s no two-handed tackling. Rugby is bloody, but there are no helmets. In football, players subject themselves to the risk of CTE in humanized car crashes, the use of helmets protecting skulls while preventing players from understanding just how dangerous head-led tackles can be. Football is dangerous, the use of helmets allowing for some of the riskiest contact seen in any sport. It was not something Victorian women would be encouraged to play, yet a few of them did. In “Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of The National Women’s Football League” by Frankie de la Cretaz and Lyndsey D’Arcangelo, the authors masterfully recount the history of women’s football, including the first time it was played: in the late 1800s.

The first recorded instance of women playing the sport was on Nov. 12, 1896. As it would be for the next century, this women’s scrimmage was set up “as the entertainment portion” for “a masked ball for a men’s social club.”

Hail Mary sets the scene as to how the first recorded instance of women’s football played out all those years ago. According to the book, the male onlookers were “so excited by the girls’ unexpected aggression they began climbing over each other to get a closer look.” The scrimmage was eventually stopped by the police “out of fear for the girls’ safety.”

In speaking about the 1896 scrimmage, the authors describe how women’s football would be regarded for the next century: “The spectacle was never meant to be taken seriously; it was merely a gimmick for those who organized it and a source of entertainment for the men who watched it.”

Aside from living in a time when most women had no financial or social independence, where football was developed matters factors into how accessible it was to women. American football was developed through intercollegiate games between Harvard, Yale, Rutgers, Columbia, Tufts, and McGill. In that 1896 scrimmage, the participants were even pinned with Yale and Princeton colors, but women could not openly enroll as undergraduates at Princeton or Yale in 1896.

Although Elizabeth Cary Agassiz founded Radcliffe College for women in 1879, women were not allowed to attend Harvard College until World War II. There were few integrated educational opportunities during the 1800s, and there was no women’s collegiate equivalent to American football as it began. Walter Camp created the modern game at Yale, and it began to take off at colleges and universities across the United States.

The institutions that once forbade female students still haven’t created football programs for them, and as they have throughout history, women have had to fight for every inch of daylight when it comes to advancing their athletic interests. In 1920, the same year the NFL was created, there were women playing football at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota.

In the 1920s, there were several instances of women playing tackle football in “exhibition” games. In 1923, women at Gustavus Adolphus College played an exhibition game of football in “borrowed men’s uniforms.” Another Gustavus Adolphus source notes that “the First ‘Women’s Football Classic’ football game between the ‘Heavies’ and the ‘Leans’ made national news.”

In 1926, a women’s football team called the Frankford Lady Yellow Jackets played as entertainment during halftime for the Frankford Yellow Jackets, a Philadelphia Eagles predecessor that won the NFL Championship that season. The Lady Yellow Jackets were “set to compete against a couple of men in a brief and playful scrimmage, much in the same way a court jester was trotted out in front of a king to elicit laughs from the royals,” according to Hail Mary. The women were recorded as “cavorting and performing the Charleston”, but there’s no indication any football was indeed played.

An often-overlooked chapter of women’s football history in that era is the 1926 Cavour High School football team in Cavour, South Dakota. Facing a low turnout for the high school boys’ football team that year, a group of girls faced off against one another as the Alphas and Betas.

“Their existence was short-lived and eventually squashed by prevailing authorities, but for a few weeks in central South Dakota in 1926, a group of female football players put a town on the map as a community rallied behind its favorite football team,” recalled Chantel Jennings for The Athletic.

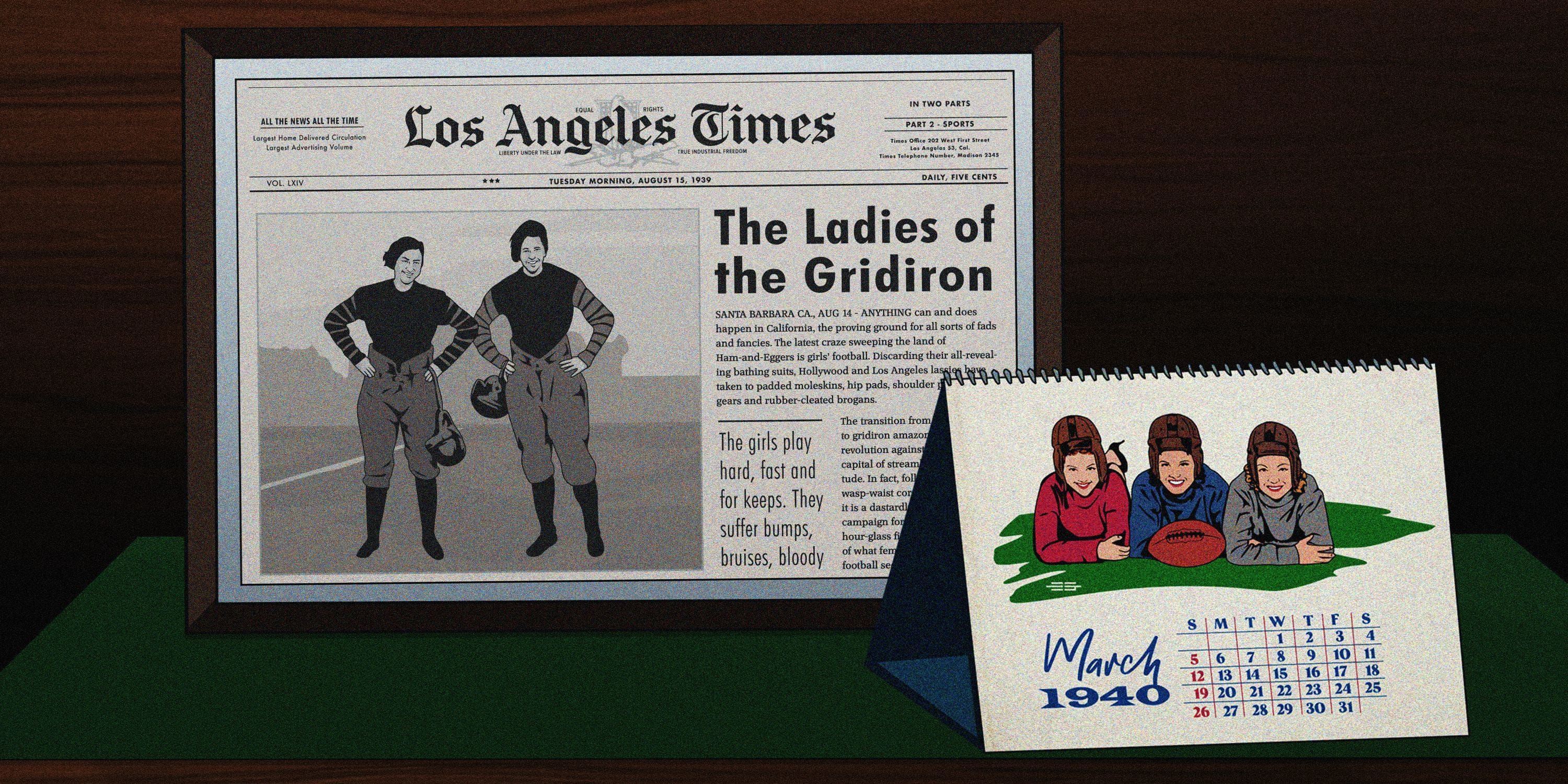

Women’s football made national headlines again in 1939, but this time, it was across the country in Los Angeles, California. A women’s softball team called the Marshall-Clampett Amazons doubled as a football team, although they were primarily softball players. On Nov. 22, 1939, the Marshall-Clampett Amazons played the Chet Relph Hollywood Stars in the first full-contact, non-exhibition women’s football game. The Los Angeles Times covered the game, and Life Magazine featured the players and game in their November issue.

The Life profile praised the athletes for their play. “Strangely enough, they played good football, seldom fumbling or running away from their interference,” read the article.

What the Life write-up proves is that at least in 1939, women’s tackle football was on full display, and it garnered the respect of some sports journalists and the attention of thousands of fans. There was a market for women’s football; a desire to play and watch them play. But outrage from prevailing misogynistic medical beliefs drowned out the cheers for the Amazons and Stars.

“Football, they said, is a dangerous sport for girls,” the Life article forewarned, quoting uninformed doctors at the time. “A woman’s body is not heavily muscled, cannot withstand knocks. A blow, either on the breast or in the abdominal region, may result in cancer or internal injury. A woman’s nervous system is also too delicate for such rough play. It would be better, they thought, for the girls to stick to swimming, tennis and softball.” A 1939 newswire article was more blunt about the crux of the issue: women’s football was an invasion of “one of the last strongholds of masculinity.”

Softball was a preferred avenue for the Amazonian athletes because in the 1930s, there was more public interest in the more socially-acceptable sport. Softball players were able to travel internationally to Japan, and players on the Amazons were featured in a Hollywood film alongside icon Rita Hayworth. The plot of the 1937 film “Girls Can Play” illustrates how female athletes were seen at the time and how their rejection of traditional femininity grated against what a patriarchal society expected of them.

The plot revolves around a female softball player who auditions to become a secretary/model because she is apparently in want of a more traditionally feminine lifestyle. The owner of the softball team is a racketeering gangster who ends up murdering his girlfriend, a softball catcher played by a young Rita Hayworth. The gangster then pretends to be one of the female softball players and is eventually caught at the end of the film for his crimes. As ludicrous as these plot devices seem, they represent how women’s sports were seen at the time: eventually, female athletes would want to reject their athletic lives for traditional ones spent at home focusing on being conventionally attractive for potential husbands.

“The members of the fair sex better try baseball or basketball to keep their curves instead of the gridiron sport,” warned newspaper columnists in the Bradford Evening Star in 1939.

The obsession about how sports distinctly affected women’s health and attractiveness has been a historical constant. Physically-demanding athletics were perceived as contrasting the delicate nature of women, to the point that men worked tirelessly to campaign against giving women the chance to play. When Senda Berenson founded women’s basketball at Smith College in 1892, she faced a dilemma: she wanted her female students to be physically active, but she was concerned that they would experience “nervous fatigue”, which was code for “hysteria.”

Early in their development, the rules of soccer, basketball and softball were amended to make these sports more accommodating to the “fairer sex.” Still, it wasn’t enough for the men who governed athletic institutions and who fundamentally believed sports were not for women. In 1922, the AAU banned women from playing basketball, and “the reason given for barring women was that if a woman was allowed to run more than a half-mile, they would put their reproductive health at risk.”

Football was even more terrifying. As Natalie Weiner chronicled for SB Nation, that 1939 Life spread thrust women’s football into national discourse, where misinformed medical professionals and supposed athletics experts discouraged and, in some cases, forbade women’s football from spreading. Spalding issued a 1939 pamphlet titled “American Football For Women”, which listed rules for a two-handed touch game believed to be more amenable to women. Instead of tackle football, this was “a safe game for all classes of women to play because there is no tackling or blocking or any other feature permitted that would be injurious to them.”

“Stop women’s football in every way you can!” wrote University of Michigan professor Elmer D. Mitchell in the Journal of Health and Physical Education. “Do not give it a chance to grow!”

When thought translated to action, the prejudice became oppressive. In Los Angeles, the parks department that once hosted the Amazons and Stars announced they would no longer allow their fields to be used for women’s football. Two decades before second-wave feminism, the head of the parks department in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania revealed his greatest fear: that women’s football could be revolutionary, redefining what it meant to be a woman by doing the most masculine activity imaginable.

“I think the typical American girl today is a girl who is quite feminine, who has charm and poise and is really a woman,” he said. “A mannish tomboy type of girl should not be set up as an example of American womanhood; and I do think that if our girls started playing football, there would probably be created a new type of women for our girls to emulate.”

At a time when men believed women’s bodies were not suited for running and tackling was unbecoming, Professor Mitchell soon got his wish. As rare instances of women’s football popped up across the nation, they were swiftly and systemically squashed out of existence.

In 1941, a professional women’s league attempted to form, consisting of the New York Bombers, the Chicago Bombers, and the Chicago Rockets, but the league failed to build enough interest to become a viable business venture.

In 1945, Eastern State wanted to host a homecoming football game, but only three men were enrolled for the fall semester due to World War II. Similar to how women saved wartime baseball in A League of Their Own, female students at Eastern State rounded up enough jerseys to play before a welcoming homecoming crowd. They never took the field again, and women’s football virtually went dark for the next 26 years.

Part II: An illustrious, overlooked league of their own

*Note: The historical documentation of the NWFL, and the themes surrounding the importance of the league to the women involved, are a result of the painstaking research contained within Hail Mary by Lyndsey D’Arcangelo and Frankie de la Cretaz. All credit for these facts and ideas goes to them.

If Walter Camp is the Father of American Football, then Sid Friedman is technically the Father of American Women’s Football Leagues. Or, at least, he is the “P.T. Barnum of Women’s Football”, as D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz aptly describe him.

In Hail Mary, D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz paint a vivid picture of Friedman, offering in-depth context into the person who saw opportunity in giving women the ball. Friedman, an entrepreneurial Cleveland promoter in the 1960s, saw women’s football as nothing more than a gimmicky, money-making opportunity. If Friedman had the idea back then for the Puppy Bowl, which annually draws in more than a million viewers, he likely would have promoted puppies playing football instead of women. Make no mistake: Friedman was a businessman who saw an opportunity to exploit an untapped market, not an explicit proponent for women’s equality.

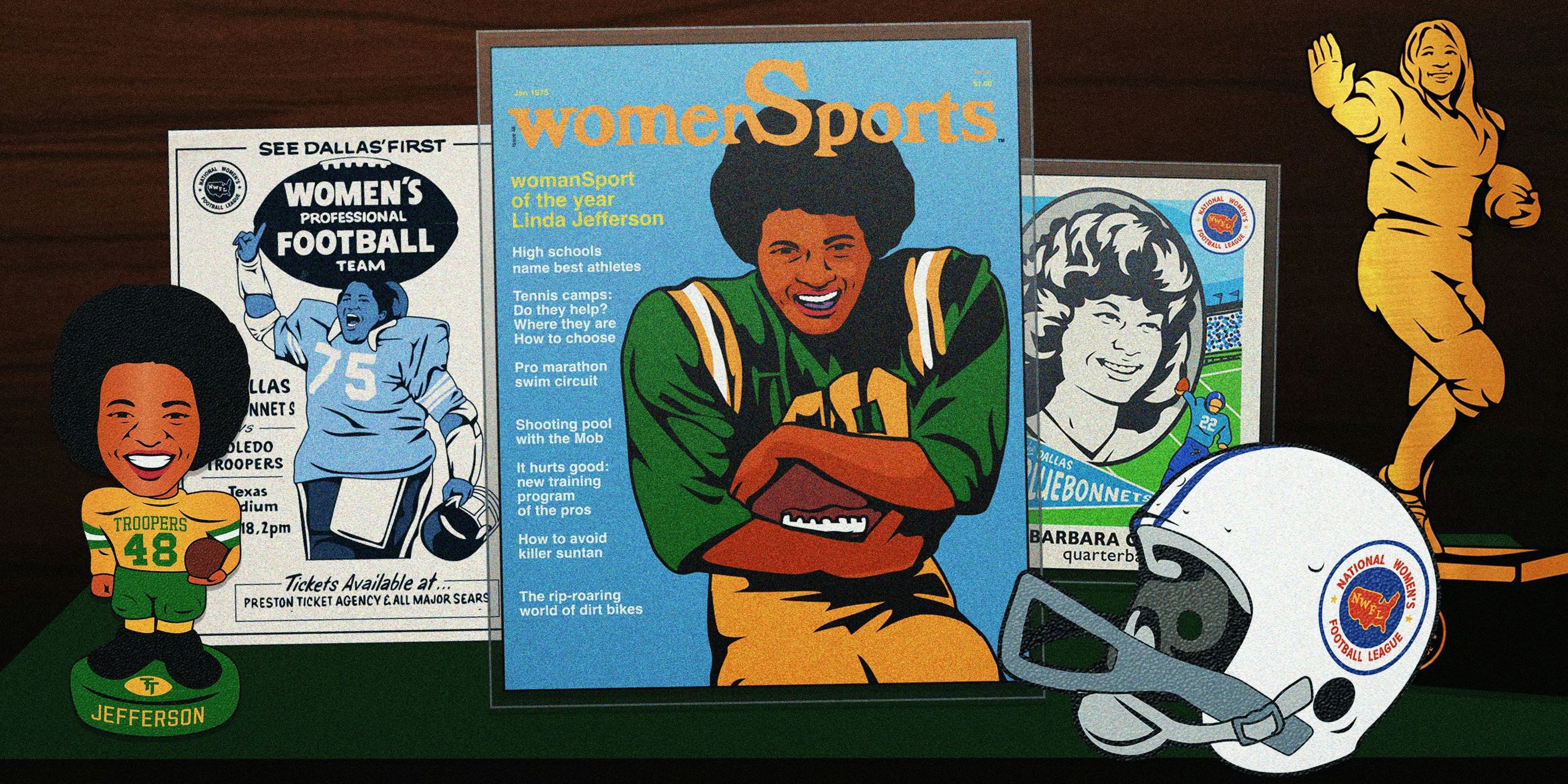

Still, as D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz delineate, Friedman was right about a few things. There were women who wanted to play football, there were thousands of fans who wanted to watch women’s football. According to the Hail Mary authors, Friedman’s rapacious nature was both his propellent and his downfall, as other owners cropped up across the country beyond his control with competing franchises. Ironically, Friedman’s Toledo Troopers — who consistently defeated his original and favored Ohio team, the Cleveland Daredevils — went on an unparalleled winning streak that puts the New England Patriots dynasty to shame: 28 wins and 0 losses over five seasons.

The league that Sid Friedman created in 1967 became a predecessor to the National Women’s Football League, the first professional American football league for women. D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz report that from 1974 to 1988, the NWFL spread to 19 cities across North America, allowing thousands of women the opportunity to play. Friedman may have been interested in little more than a stunning display of athletic prowess akin to the Harlem Globetrotters, but the NWFL allowed housewives, mothers, students and queer women from age 18 to 40 the chance to play. And while the NFL remained steadfast in its tradition of discriminating against Black head coaches, the first head coach of Friedman’s inaugural team, the USA Daredevils, was NFL Hall of Fame running back Marion Motley, a retired Cleveland Browns legend who was systematically rejected from men’s football coaching positions.

The formative era of women’s football and the decades that followed in the NWFL are the focus of Hail Mary, which serves as a comprehensive guide to what women’s football began as and became throughout the 20th century. With extensive historical anecdotes and exclusive interviews, D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz illustrate the rise and fall of the sport, answering an obvious question: if women’s professional football was founded in the late 1960s, why is the sport not bigger today?

Upon reflection, more questions arise. Why does the NFL not support a women’s league the way the NBA has partially supported the WNBA? Why, 50 years later, is it so hard for women to play football, and why is it still not widely available at the amateur or youth levels? The motivations behind creating the NWFL provide some insight as to why.

From the outset, Friedman’s league was not a feminist league created by women for women — it continued in the vein of women’s football as spectacle rather than sport. An NPR interview with D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz encapsulates how Friedman approached the game as opposed to Bob Mathews, the founder of the NWFL.

“The thing about Sid is that he cared more about publicity than he did about the game. Some of the coaches he recruited were former NFL players, and so they were serious in that regard. But then he also envisioned things like tearaway skirts and jerseys, and he reportedly sent a Hustler photographer out to practices to photograph the women who were appropriately horrified by this.”

When male onlookers weren’t condemning or mocking women’s football, they were busy gawking at some of the women who took the field. Gail Dearie, a wide receiver for the short-lived New York Fillies, became the poster woman for the sport in a 1972 Life Magazine spread. Dearie’s statuesque frame that made her a talented wideout also made her a prime modeling candidate, as she modeled professionally before playing with the Fillies. An attractive blonde woman, Dearie was portrayed as a juxtaposition between the manly rigors of football and the gentle femininity in her role as a beautiful wife and mother.

The headlines made that all too clear, with those in the media fawning over Dearie for her looks and her unexpected choice to play football rather than her actual athletic performance. Dearie and her teammates “forsake the steam iron for the gridiron”, as one newspaper put it, undermining the rigidity of women’s societal roles at that time.

Although funding female athletes and displaying their games on national television — treating them as equitable to their male counterparts — remains a contentious struggle, sexualizing female athletes has always been quite easy for male fans. Even in the first recorded moment when a woman picked up a football, there was a crowd of men jostling to ogle them. The insidious suggestion of tearaway skirts gave way to the Lingerie League, which then became the Legends Football League.

Despite lacking medical insurance and sufficient equipment, which eventually led to a lawsuit, these leagues featuring scantily-clad football players have offered one of the only paid, highly-televised opportunities for women’s football players. The entire 2015 Legends Football League season was aired on Fuse, while the Women’s Football Alliance (WFA), one of the nation’s major semi-pro women’s tackle football leagues, will only have their championship game aired on ESPN2.

Hail Mary emphasizes that since the 1970s, men have editorialized the narrative of the sport, interviewing male owners and coaches to justify the value of the sport over the athletes themselves. D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz note that sports journalists usually interviewed Friedman rather than the players, and Friedman may have inflated attendance numbers to bump up ticket sales. To an extent, this worked: Friedman’s barnstorming USA Daredevils played against men’s teams in 1967, but playing against the all-women’s Detroit All-Stars and nearly defeating an all-men’s team from Erie, Pennsylvania showed Friedman that this was a viable business venture.

The USA Daredevils became the Cleveland Daredevils, and Friedman founded four other teams by the fall of 1971: the Pittsburgh Hurricanes, the Toronto Belles, the Buffalo All-Stars, and the Toledo Troopers. Friedman lived by the mantra of speaking things into existence, and his tenacious optimism did get him an early foothold in women’s professional football. But his stubborn refusal to accommodate other franchises and his desire to own and control an entire league became a hindrance in the decade to come.

The growth of women’s football during a decade heralded for advancing women’s rights is no coincidence, but the players at the time did not see themselves as pioneers of feminist philosophy. Some players adamantly clarified that they were not “women’s libbers”, the derisive term that attempted to reduce the women who were fighting for gender equity at the time.

In a sense, playing football was a down-to-earth, grassroots way of fighting back against what women were supposed to be. The players were motivated by their love of the game, but they weren’t hindered by their gender identity, sexual orientation, race, religion, or any other sociological identifier. In a time when lesbians were being persecuted by the police, Black women just began to grace the covers of fashion magazines, and Billie Jean King became a champion for the ages in the “Battle of the Sexes”, women came together in communities across the nation for a simple reason: to play the game of football. Some were lifelong athletes, some grew up as football fans, and some showed up to tryouts out of curiosity. Everyone who made it past the multiple rounds of competitive cuts stayed because they felt they found family, a theme that is repeated in every narrative about women’s football.

Real or imagined, heroes offer strength, protection, hope and salvation, and athletic heroes show young people what their minds and bodies can achieve, no matter their form. The women who played football at this time weren’t doing so with lofty goals in mind, but Los Angeles Dandelions quarterbacks Rose Low and Vickie Garcia showed the young Asian American girls and Latina girls in Los Angeles what they too could become. Dandelions outside linebacker Barbara Patton brought her two young children to watch her practice. Her son, Marvcus, emulated his mother’s tenacity on the field as an NFL linebacker who played from 1990 to 2002.

“I thought it was really cool to tell my friends that my mom was a linebacker,” Marvcus once said.

In November 1974, Patton herself graced the cover of womenSports Magazine as one of the first Black female athletes to be featured on the cover of a sports magazine. A few months later in 1975, legendary Troopers running back Linda Jefferson was voted as the inaugural “WomanSport Athlete of the Year.” Jefferson wasn’t the most famous female athlete of her time, but in this contest, she was the most beloved: her votes came in droves from the devoted fans in Toledo, Ohio. At 5-foot-4 and 130 pounds, Jefferson ran for nearly 9,000 yards and scored 140 touchdowns over her illustrious career, which garnered her a 1973 Ebony cover in addition to her womanSport cover. Unlike NFL Draft scouts who obsess over physical characteristics, casting off players who are an inch short or a second behind, the NWFL proved what different builds could accomplish when given the chance.

Football also appreciated big women who were often not treated with the same respect in society. While media outlets callously commented on the appearance and weight of football players as they played, the women themselves felt that their bodies were appreciated for their strength rather than rejected for their failure to adhere to a societal ideal that prized thinness.

“On a fundamental level, you need every body type in football,” explained Holly Custis, a 16-year veteran linebacker who was inducted into the Semi-Pro Hall of Fame Class of 2018. “Something I noticed about women’s football is that bigger men are taught that it’s okay to be big because we need your size. Bigger women are not taught that. So I have noticed that football has given bigger women an outlet they haven’t really had before, and that’s beautiful.”

Football allowed women to just be, and the martial nature of the game brought out aggression, power, ambition, and unbreakable bonds. It brought out the best in them.

Friedman may have been the first to truly start a women’s football league, but the idea was not exclusively his own. Within two years, there were other women’s teams cropping up around the United States. The Toledo Troopers and Detroit Demons, teams that once “belonged” to Friedman, soon longed to grow beyond his limited view of what women’s football could be. These teams wrangled ownership away from Friedman’s grasp in order to manage themselves, with the Troopers and Demons creating a fierce, competitive rivalry that once erupted onfield in an all-out brawl, according to Hail Mary. But football would not be Ohioan forever, as the sport took hold for women in America’s other football mecca: Texas.

It was no coincidence that Ohio became the birthplace of women’s football, and Texas began growing the league that eventually became the NWFL. D’Arcangelo and de la Cretaz poignantly describe what football meant to girls and women in Ohio and Texas, giving context to why women in these places fought to play the sport that was in their blood.

“For girls growing up in this culture, forced to always be the spectator — in Ohio and Texas, yes, but also anywhere in America — it was only natural that there would be an overwhelming feeling of missing out. While there may have been other sports that were becoming more accessible to girls in the seventies, like rec league basketball or softball, those sports were consolation prizes. As much as the girls loved playing them, in Ohio at least, football was the sport: lionized by their friends and family, and always off-limits to the girls. If they were lucky, they could scrimmage with their brothers or the neighborhood boys, but that was as close to tasting organized football as they ever thought they could get. The reality of putting on pads and helmets and jogging out onto a real football field, with fans in the stands cheering them on, was one that existed only in their wildest daydreams. Even though girls were gaining ground in other sports leading up to and after the passage of Title IX, they were still shut out of football. And, in Ohio, this meant shutting girls out of the sport that mattered most.” (Hail Mary, pages 72-73)

Despite the gridiron fervor women felt in football country, it was men who saw opportunity in football and launched their own teams.

The Mathews Brothers were the ones who grew the idea of women’s football far beyond the Rust Belt. Joe and Stan Mathews created the Dallas Bluebonnets in 1972, and their older brother, Bob Mathews, felt inspired to invest in his own team in Los Angeles. Although Hail Mary describes the time that Joe Mathews asked the Bluebonnets to “wear a dress on the plane” and was loudly laughed out of the locker room, all three Mathews Brothers largely treated the athletes as they would any male athlete at the time. They recruited coaches, sought investors, and promoted the team to give it a genuine chance of success.

By 1974, there were seven professional women’s football teams spanning the United States, and it was Bob Mathews who created the National Women’s Football League that same year.

The NWFL initially consisted of the following teams: the Toledo Troopers, the Detroit Demons, the Dallas Bluebonnets, the Los Angeles Dandelions, the Columbus (Ohio) Pacesetters, the Fort Worth (Texas) Shamrocks, and the California Mustangs.

Notably, the NWFL’s executive director was Joyce Hogan, a part-owner of the Dandelions alongside her husband. Women’s football was still largely owned and governed over by men — Hogan and Houston Herricanes founder and owner Marty Bryant were historical anomalies. While women’s football has continued in the legacy of female leadership, the NFL is drastically behind: there are no female NFL owners who have purchased a team themselves; all have been bestowed to them through marriage or inheritance. The NWFL didn’t just allow women opportunity on the field, but it began a tradition of recognizing female autonomy. In a pivotal decade focused on this very question, the NWFL embodied its time.

Mathews created three divisions — the South, West and East Divisions — and there were three consecutive NWFL Championship games played between the Toledo Troopers and Oklahoma City Dolls from 1976-1978. But as quickly as the NWFL came together, it seemed to unravel just as it was beginning. By 1979, Mathews begrudgingly sold the Los Angeles Dandelions, and the last remnant of the NWFL’s prime was marked by the sale of the Toledo Troopers in 1980.

The 1980s saw a continuation of the NWFL in name, but different teams populated the league for the next eight years. The Columbus Pacesetters were the only NWFL team to last from the league’s inception to its demise, with the Pacesetters folding in 1988. Many former Toledo Troopers players banded together and formed the Toledo Furies in 1983, although they recruited new players and coached the game to a new generation. In 1984, the Furies won the NWFL Championship, but by 1989, the team was pressured to transform into a flag football team as fellow NWFL teams faded away. The league withered away, and women were forced to wait 20 years until they could pick up the pigskin again in a pro league.

The primary reason that the NWFL didn’t last — because “playing a kid’s game for a king’s ransom” is royally expensive — was influenced by both the nature of business and the culture of valuing women’s sports.

As D’Arcangelo told FanSided, it’s common for a sports team to remain unprofitable within the first decade of its creation. Essentially, sports teams originate as cavernous money pits, which makes sense when considering the fact that athletic individuals are being paid to play a game that thousands, and even millions, will tune in to watch. Owning a sports team can be immensely profitable, but for the billionaires that own professional men’s teams in the United States, it’s merely another acquisition.

Sure, Robert Kraft grew the Patriots’ valuation from $172 million in 1994 to the $5 billion price tag the team wields today, but Kraft bought the team as a paper titan with wealth to spare. It’s a far cry from the Mathews brothers, who scrounged up a couple thousand dollars and a few investors and could only pay their players $25 per game. It’s even further from the Houston Herricanes, the competitive NWFL team started by Marty Bryant. Without investors and as a female owner, Bryant was unable to pay players, using any funds made from games to cover stadium costs, ambulance fees and other game-facilitating measures, according to Hail Mary.

What separates men’s and women’s teams is that time and time again, wealthy owners continue to pour money into fledgling men’s franchises, growing them over decades. Men’s teams are given patience, and in turn, the culture surrounding them is permitted to flourish. While none of the original NWFL teams still exist today, it’s important to note that 90 percent of early NFL teams failed, too. The 10 percent that survive today had people who we were willing to invest in them. And for those that can’t invest money, investing fandom is just as necessary.

If a billionaire buys a sports team no one wants to watch, it’s easily an example of bad business. But growing a franchise, and thereby growing its fanbase, is what makes a sports franchise a winning investment. The pathetic New England Patriots were on the brink of being sold when Kraft, a longtime fan, saved the day and eventually turned the team into a dynasty. The three ingredients to grow a team’s value — time, money, and wins — combined to grow the Patriots’ value 30 times in 28 years. The Toledo Troopers had a little time, a lot of local support, and an unparalleled win streak, but it wasn’t enough without the money.

Even though men’s sports franchises face the same challenge of early survival, the difference is that men’s teams are afforded patience while women’s teams are not. It’s important to note that the WNBA is only 26 years old compared to the 75-year-old NBA, but the reluctance to invest in the WNBA uniquely affects women’s basketball. Twenty-six years in, the WNBA is going to see 25 games nationally broadcast on ABC, ESPN and ESPN2 in the 2022 season. The Los Angeles Lakers had 42 national broadcasts in 2021-22 alone. That helps to explain why WNBA players are paid more money overseas than in the United States. With rare exceptions like athlete entrepreneur Skylar Diggins-Smith, there is still little money in women’s basketball, with many singular NBA players making more money than an entire WNBA roster. The discrepancy in player pay and decreased televised coverage hints at a sinister belief present in women’s sports leagues: the belief that no one wants to watch women play sports.

Friedman imagined women’s sports as a spectacle, while Troopers coach Bill Stout and Bob Mathews believed in keeping the integrity of the women’s game. Despite their efforts, it was difficult to grow the Troopers’ attendance to cover the cost of operation without a billionaire backer. In absence of that wealth, what could have helped the game was positive media coverage, but Hail Mary remains the holy grail of recorded history for women’s football. The book illustrates how in the 1970s, few outlets were interested in covering women’s football, with one Houston editor throwing a Herricanes press release right in the trash.

The journalistic gatekeeping that deemed women’s football was worth nothing more than the occasional feature meant that potential fans were not being introduced to the teams. And when newspapers and television stations did send out reporters, their stories were often shaped by the lens of condescending male journalists who hardly interviewed players about their actual game. Hail Mary notes that there were a few rare exceptions (in an industry that is still predominantly male) where female journalists were able to tell captivating stories about the sport, and male journalists recapped games with the same respect afforded to professional men’s teams.

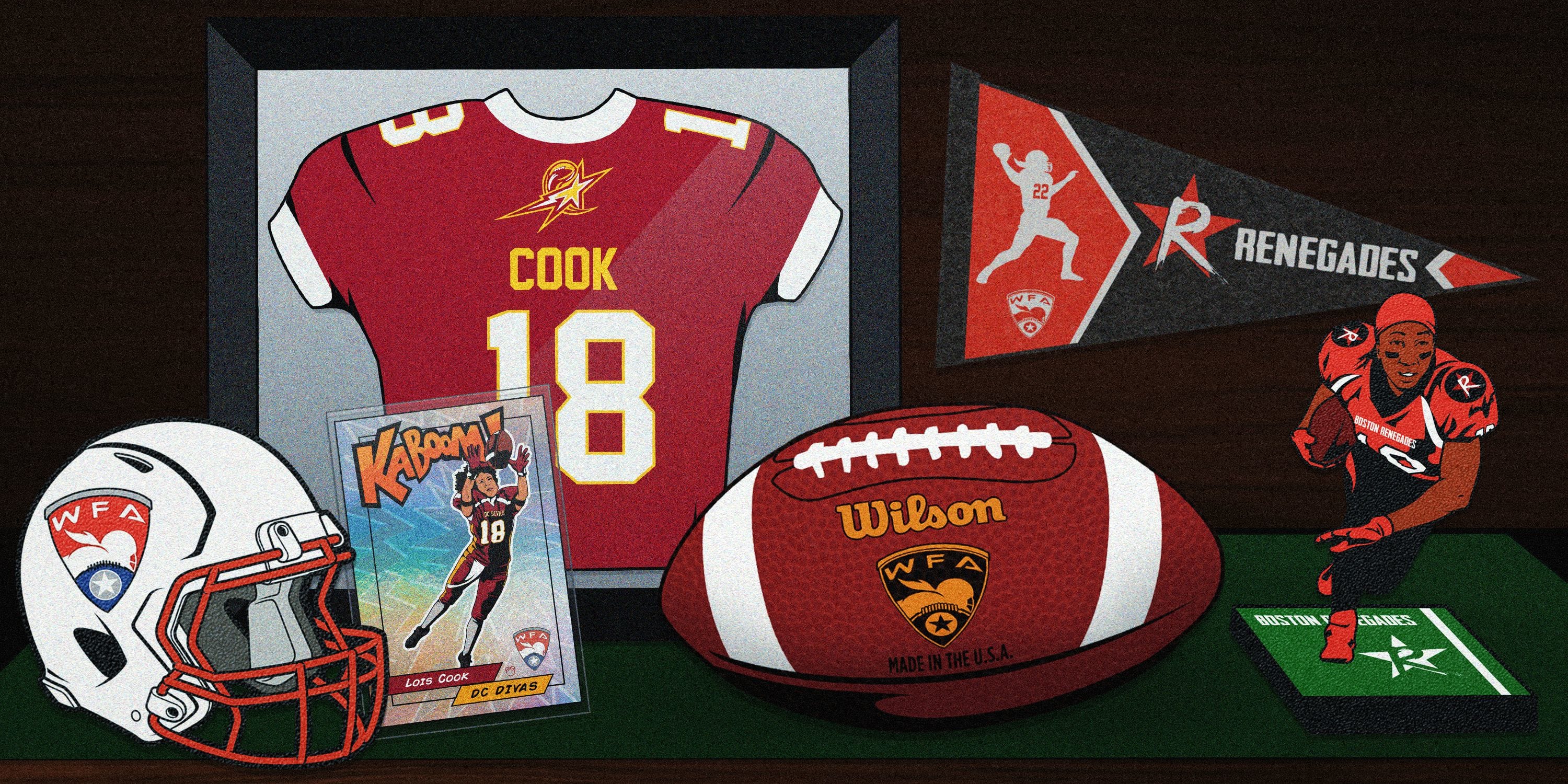

Today, social media allows women’s footballers to take some of the outreach into their own hands. D.C. Divas wide receiver Lois Cook has amassed 5 million likes on TikTok for her creative videos, but individual fandom only goes so far. Sports media must make a concerted, consistent effort to cover women’s sports in order to set the newsworthy value and instill a culture of fandom. After all, how can fans fall in love with a local team they know nothing about?

For the women who caught wind of the sport and the owners and coaches who believed in them, starting a team might have been within the realm of possibility. But growing a women’s football franchise during the 1970s with essentially no financial backing proved impossible. And the fact that Bob Mathews downgraded the Los Angeles Dandelions from a professional team to a semi-professional team to avoid exorbitant insurance costs still shapes the game: there are no women inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but there are women who have recently been inducted into the Semi-Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Although the NWFL fell apart, it finally began a movement that wouldn’t stop. The Columbia Pacesetters managed to play through the 1970s and 1980s, and women’s football persisted in the Rust Belt region for nearly 20 years. Women’s football still resembles those early NFL teams, with innumerable small-market franchises.

Women’s football was here to stay, but not in the same form. In 1999, the Women’s Professional Football League formed, which is erroneously credited as “the first women’s professional American football league in the United States,” according to Wikipedia. Oddly enough, the WPFL had the exact same concept as Friedman: seeing women’s football as a worthwhile venture, women tried out to go on a barnstorming tour and perform in exhibition games. Players were promised $100 salaries per game that they were never paid, but the league restructured and held a WPFL Championship every season until 2007.

A multitude of leagues spawned between 2000 and 2003, with most of them folding by 2003. There was the Independent Women’s Football League (IWFL), the National Women’s Football Association, the Women’s American Football League (WAFL), and the American Football Women’s League (AFWL). The IWFL was long-lasting, spanning from 2000 to 2018. It was the only league formed around the turn of the century that lasted for more than a decade, and most of the teams within the IWFL still exist today within modern conferences.

Today, there are two major leagues: the Women’s Football Alliance (WFA) and the Women’s National Football Conference (WNFC). D.C. Divas wide receiver Lois Cook and Boston Renegades wide receiver Adrienne Smith play in the WFA; linebacker Holly Custis plays for the Utah Falconz in the WNFC. Mary Pratt-Lauchle joined the Central PA Vipers alongside Lori Locust, and Pratt-Lauchle went on to be an owner and founder of the Keystone Assault, which is now defunct. Before the Assault saw their last season, they got a shout-out from legendary Pittsburgh Steelers wide receiver Hines Ward. Ward was unfamiliar with the team, which was located three hours from Pittsburgh and played its games at Lower Dauphin Middle School rather than Heinz Field.

In women’s football, leagues and teams seem to come and go, with few surviving long enough to become notable franchises. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the WFA’s Boston Renegades might be the next iteration of the Toledo Troopers. Boston teams have been around since 2001, with the Massachusetts Mutiny becoming the Boston Rampage becoming the Boston Militia becoming the Boston Renegades. But in that time, Boston has been consistent about one thing: winning.

Boston teams have won six championships, four conference titles and eight division titles. The Renegades won three of those championships.

Although women’s football has been fated to repeat the patterns of poor financing and a difficulty in holding firm, it seems that women’s football may be reaching critical mass. In 2022, there are two professional-level conferences with a multitude of teams, players with high-profile athlete endorsements, more media exposure than ever, and brand sponsors like Wilson and Secret.

Smith proves that the Renegades culture is already growing in Boston, where she gets recognized as a Renegade in grocery stores. The final step is for all post-Millennium football leagues to finally fold into one league, the way the AFL folded into the NFL and the solidified league grew from there. The WNBA has had 26 years to grow as a cohesive league, and women’s professional football still hasn’t been unified under one crest. Once that happens, the league can step forward and the sport can reach its eventual goal: to pay athletes for their play, to have owners receive a return on their investment, and to have fans access games.

But even if women’s football accomplishes all of this at the highest level in the 2020s, these athletes will still be playing from behind their male counterparts. Unless Title IX changes, girls’ and women’s football still won’t be offered at schools and universities across the United States.

Part III: Equal women’s football access on a pee-wee-to-pro pipeline

“[Football is] the last bastion of hope for toughness in America in men, in males.” – Jim Harbaugh, 2015

This was the knee-jerk reaction to seeing a young girl play football, but it wasn’t uttered in 1959, the year Barbie first hit department store shelves.

It was said on national television in 2012 when a nine-year-old girl named Sam Gordon went viral for terrorizing the field in her Utah PeeWee Football League as its most explosive player.

Gordon played on both sides of the ball, scoring 25 touchdowns and racking up 65 tackles in her youth league. No one was prouder than her father, Brent Gordon, who posted her reel to YouTube and made Sam a star overnight.

“My family was always a football family,” Gordon told FanSided when reflecting on her first football memory. “I know we all threw the ball around constantly, but my first real football memory is playing at recess against the boys. I remember thinking of it like sharks and minnows, still excited to prove myself against the other boys. I remember juking out the other team, and celebrating with mine when I scored. I’ve loved football for a long time.”

Going viral is one thing, but staying culturally relevant is entirely another. For those who chase fame and fortune, their stars often fade quickly. Instead, Sam rose to continuously higher heights, breaking ground in a way few teenage girls could dream of doing, and that’s because of one thing: Sam was genuine, and she kept doing the work. Gordon sat alongside feminist icon Gloria Steinem, spoke at the 2015 espnW Summit, was featured in the iconic NFL100 anniversary commercial, and was awarded the inaugural NFL Honors Game Changer Award in 2018.

“I want to let you all in on a little secret… girls love football,” Gordon shared as she began her acceptance speech for the award.

What Sam has done in the spotlight is changing the course of women’s football forever, because Sam is the reason there are young girls playing the game in Utah. A shared tragedy for many WFA athletes is that after dominating in Pop Warner and PeeWee football with the boys, they always had to hang up their pads and cleats in high school. Sam didn’t want to, and she knew there were hundreds of Utah girls who didn’t want to either. With the help of her family and community, Gordon founded the Utah Girls Tackle Football League, which was the first all-girls tackle league in the United States.

Gordon’s league grew from 50 players to over 600 in a matter of years, and a recent endorsement from Under Armour allows Sam’s influence to spread even further. Now, Gordon will be hosting two UA Next football camps, debuted Under Armour’s first set of women’s football cleats, and Under Armour became the official sponsor for the Utah Girls Tackle Football League.

“The biggest misconception about women playing football is that they don’t want to,” Gordon said. “Which is entirely false — there are so many women who want to play the sport, but are discouraged because they don’t have the opportunity. That’s what Under Armour and I are working to solve: to increase access to the sport and establish pathways for aspiring female football players of all ages.”

Fifty years ago, the Dallas Bluebonnets were star-struck playing in the home of the Dallas Cowboys, and women’s football players sewed kneepads into the chest pads of their uniforms because football gear wasn’t made for women. Today, Sam is rolling out football cleats designed for girls, and her 36-team league will play at the University of Utah’s Rice-Eccles Stadium so they can play under the lights — just like the boys.

“THAT’S the dream right there!” Gordon told FanSided. “There’s absolutely nothing like playing under the lights, and I’m so glad more girls will now have the opportunity to do so.”

Sam has been awed and revered for a decade because as one person, she promoted a revolutionary thought — that girls should be able to play football — and in the 2010s, she was empowered as a young girl to turn that into a reality. Sam’s journey shows that so much has changed over the years because millions of women have fought to have their intellect acknowledged, their bodies respected, and their voices heard. Women banded together and pushed to play in professional leagues, and it hasn’t stopped since the 1960s. Despite the progress, Sam is still managing to break new ground because the playing field remains uneven for men and women.

As Gordon puts it, there is effectively no “funnel” that allows girls like herself to progress through PeeWee leagues by solidifying fundamentals in high school and crystallizing potential in collegiate programs. It’s jarring because after 50 years of Title IX, there remains no academic equivalent to men’s high school and college football programs. That is by design: Title IX isn’t supposed to let girls and women play football; it’s meant to prevent it.

Gordon is the latest in a long line of girls and young women who want to play football in school. According to the College Football Hall of Fame, “women have been linked to college football from the beginning,” but it was never as players — it was as seamstresses sowing uniforms and flags. In 1892, the women at Livingstone’s textile school stitched uniforms for Biddle and Livingstone, the two teams playing in the first-ever HBCU game. Later, Irma Beede became known as the “Betsy Ross of Football” because she sewed the first penalty flags together, which were used by her husband, Youngstown State coach Dwight “Dike” Beede, in 1941.

Women didn’t score in men’s college football until 1997 when Willamette kicker Liz Heaston scored a field goal. Since the turn of the millennium, women have been peppered in throughout collegiate games primarily as kickers, although free safety Toni Harris made a historic stride as “the first female skill-position player to sign a letter of intent on scholarship in college football history.” For now, the only way that women can play college football is on men’s teams — there are no NCAA equivalents, which should theoretically violate the spirit of Title IX. Because of the Contact Sports Exemption Clause, it doesn’t.

Title IX celebrates 50 years of existence in 2022, as the law has worked tirelessly to close the gender gap in schools. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 states the following:

No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.

Of course, there’s a catch — or an exemption, rather. Title IX was intended to offer equal educational opportunities, but not necessarily athletic ones. Ever concerned about leeching wealth from athletic talent, the same NCAA that didn’t want male athletes to make money off of their name image or likeness didn’t even want women to play college sports — because it would just drain money from men’s programs.

Per Brittany K. Puzy documenting the history of Title IX in regards to baseball: “Specifically, the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) lobbied against the inclusion of athletics under Title IX, largely because it assumed that Title IX would ‘drain needed resources from men’s programs,’ and would cause the ultimate demise of men’s sports programs.”

The 1974 Javits Amendment required regulations to Title IX that allowed high schools and colleges to reject the notion that equivalent girls’ leagues were required in contact sports.

[W]here a recipient [of federal funds] operates or sponsors a team in a particular sport for members of one sex but operates or sponsors no such team for members of the other sex, and athletic opportunities for members of that sex have previously been limited, members of the excluded sex must be allowed to try out for the team offered unless the sport involved is a contact sport.

Every federally-funded educational opportunity available to boys and men should be available to all other genders, too, but the Contact Sports Exemption allows institutions to shirk this responsibility. The locker room discrepancy that went viral in Women’s March Madness in 2021 proves there’s a long way to go in college women’s basketball, which isn’t surprising considering that the NCAA saw female athletes as resource-draining rather than resourceful and worthy of investment. But in football, the NCAA hasn’t even bothered to create a path for women. They don’t have to.

“I see no reason for women’s football to be any different than men’s football,” Gordon said. “Female athletes deserve the same opportunities: camps, pee wee to high school to NCAA programs, a funnel to a professional league.”

Gordon believes that the lack of women’s football programs at schools and universities is a flagrant violation of Title IX, or at least, it should be.

“Last year, a few teammates and I unsuccessfully challenged the Utah High School Athletic Association to have women’s tackle football sanctioned as a sport,” Gordon said. “That decision is now being appealed.”

The federal judge presiding over Gordon’s case reasoned that “Utah school districts aren’t legally required to create a separate team because girls who want to play football can play with the teams traditionally filled with boys.”

de la Cretaz explained how this decision ties into the Contract Sports Exemption.

“Title IX prohibits contact sports, and football is a contact sport,” de la Cretaz explained. “When Title IX has been challenged around football, the girls have always been told that they are entitled to try out for the boys’ team because it exists, but when it comes to actually starting a girls’ team, that’s where it gets stickier because the clause in Title IX around contact sports specifically.”

This concept is further explored in “Playing With the Boys: Why Separate is Not Equal in Sports” by Eileen McDonagh and Laura Pappano. McDonagh and Pappano “show that sex differences are not sufficient to warrant exclusion in most sports, that success entails more than brute strength, and that sex segregation in sports does not simply reflect sex differences, but actively constructs and reinforces stereotypes about sex differences.” That’s what the Contact Sports Exemption does: it reinforces this notion that contact sports like football are too dangerous for girls to play, therefore it’s not a federally-protected equal right in the United States.

At the highest level, attitudes about women’s football remain “paternalistic”, as de la Cretaz describes, allowing schools to say no to girls’ football. But as Gordon and D’Arcangelo note, the pipeline is the future. Without it, girls will always play from behind their male counterparts who spent their youth practicing football fundamentals, and they will have to work so much harder than men to catch up and surpass male athletes as adults.

Lori Locust and Mary Pratt-Lauchle proved that women can do exactly that in their 30s and 40s, but they should have had the chance to play sooner in life. Unless the exemption, which is also a clear contradiction to the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, is overturned, leagues like Gordon’s are the only ones offering American football players true freedom.

The only way to rectify this is what Sam has been doing with every fiber of her being for over a decade: by creating a football league for girls.

“The massive gap in participation opportunities between boys and girls is solely due to boys’ football,” Gordon said. “Equality in athletics can never be achieved without separate girls football teams. At the end of the day, women and girls deserve the same opportunities as men and boys, especially when it comes to sports. I’m going to continue fighting for that until we have it.”

Without their own league, girls and women are forced to try out on men’s teams, where their roles are often limited to special teams players in non-contact roles. Collegiate women have proven they are capable kickers, but this never leads to opportunities in the NFL. NWSL legend Carli Lloyd is a World Cup champion who kicked a 55-yard field goal at a Philadelphia Eagles practice in 2019. Although Lloyd said she was “seriously considering” NFL offers, nothing materialized. Although Lloyd could have earned a quirky NFL nickname like “Lloyd The Leg”, the reality is that her leg is more valued as a women’s soccer legend than an NFL kicker. If it were just as lucrative to be a women’s football player, perhaps Lloyd would be a placekicker.

In a way, Lloyd’s path mirrors Gordon’s trajectory. Despite Gordon’s overwhelming passion for football, she is a freshman defender for the Columbia University Lions. There are plenty of professional athletes who are two-sport athletes in college, and Sam played soccer before she ever played football. The problem is, she can’t be a two-sport athlete because she can’t even play football at Columbia. Sarah Fuller, the Vanderbilt athlete who made news when she kicked for the Commodores in 2020, played soccer in college. Today, Fuller is the goalkeeper for the Minnesota Aurora FC of the USL W League.

It’s difficult to imagine forcing WNBA stars to try out on NBA rosters or pressuring the winning NWSL to play alongside men, but that is exactly what Sam Gordon was told when she wanted to sanction girls’ football in Utah schools.

A tireless advocate, the 19-year-old student, athlete and activist isn’t slowing down in her pursuit of equal opportunities for female athletes.

“I really just want to continue fighting to make football more accessible for female athletes,” Gordon said. “I started when I was nine and see no reason to slow down, especially now that I have the support of Under Armour. I hope to one day see women’s football leagues across all levels of play, more female coaches and refs in the sport…That’s what I want my legacy to be. When people hear my name, I want them to think: ‘Oh, yeah. She changed the game for women in football.’”

The truth is, Sam already has changed the game for women in football. Gordon’s league inspired similar ones in Indiana, Georgia and Canada. When Mary Pratt-Lauchle hears her name, she thinks about the future.

“Think of how many 19-year-olds do that,” Pratt-Lauchle said, marveling at Gordon’s drive. “That just shows the passion and the love for the sport, to put that much time and effort [into it]. As a mother of a 21 and 23-year-old, I know what they were thinking about it 19, and it wasn’t challenging the federal court system, so kudos to her.”

“It’s extremely important,” Custis said of Gordon’s push for a better pipeline. “I actually met Sam when I was playing with my old team in Portland and we went down and played a team in Utah, and she was, I don’t know, like 13, 14… she was really little. And it struck me that she didn’t think it was a big deal, which was great, because for her, it wasn’t a big deal that women and her as a girl were playing — it was just like a girl that wants to play soccer or basketball or run track. That’s really where we want to get to, where women and girls feel like, ‘Oh, it’s not a big deal.’” Custis noted that many of her Utah Falconz teammates have coached in Gordon’s league, have their kids playing in Gordon’s league, or are involved with the league in some way.

“I think people like Sam Gordon are gonna have a big influence,” D’Arcangelo said. “I know it seems like Sam’s sphere of influence is really in the state of Utah, but it goes beyond that.”

If women’s football looks different within the next decade, it will likely look like this: more people are aware of the sport because of the ESPN2 broadcasting deal, the various leagues could unify into one league the way the NFL once did, and there will be a broader pipeline allowing girls to grow in the sport.

“I also think 10 years from now, there’ll be a better pipeline than there is today,” D’Arcangelo continued. “Largely, I think that’ll happen with flag football. You’re seeing a lot of flag football for mixed boys and girls, but also just separate girls leagues at the youth, middle school and high school level. Now, they’re organizing teams and leagues. I think we’re gonna see that grow and we’re gonna see a lot more of that. And we’re gonna see more girls and women and whoever getting involved in football at a younger age, learning the game at a younger age, getting those fundamentals that we talked about, and yeah, I just, I really see that pipeline growing in a way that it hasn’t before.”

“As these girls now are becoming more accepted at a younger age, they are going to start challenging things more and they’re working harder and they’re playing harder and they’re showing up for high school football tryouts and, and proving, ‘Hey, I deserve to be here,’” Pratt-Lauchle said.

“And should they have to prove that? No, but you know what, sometimes that’s a little bit part of the challenge. And I think women who want to challenge the status quo are okay proving that they belong there. And that’s kind of like Lori [Locust] — she doesn’t have to talk about being a woman. She proves that she belongs there in other ways, and it’s her knowledge and her love of the game.”

In 1970, historian Howard Zinn made a powerful observation about the nation of revolution: social change must be embraced in belief over time, as a blow of arms will never change minds. “Revolution in its full sense cannot be achieved by force of arms,” Zinn said. “It must be prepared in the minds and behavior of men, even before institutions have radically changed. It is not an act, but a process.”

Zinn’s quote excluded women from historical movement, but Susan Brownmiller didn’t. That same year, she wrote in New York Magazine that “the women’s revolution is the final revolution of them all.”

Both Zinn and Brownmiller are right. Fighting for women’s football has been a decades-long process accelerated by the women’s rights movement, and winning the fight for women’s football may just be the final revolution for women’s sports. Football is violent, but it is more than that: it is intricately tied to American masculinity, and for more than a century, men deride and doubt women who want to play the same game.

But America is changing as it accepts the truth that women love football, and with it, so is the face of America’s game.

For all the latest Sports News Click Here