Their newborns were taken at birth. Years later, these women still don’t know why | CBC News

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Three Ottawa women say they were left traumatized after giving birth in hospitals across Canada, where child welfare authorities threatened to, or actually took their newborns away without explanation.

Today, these women say they are victims of birth alerts but the path to answers isn’t easy.

Birth alerts are notifications issued by child welfare agencies to local hospitals about pregnant people who they deemed “high-risk.” In turn, health-care providers are required to alert welfare authorities when the subject comes to seek medical care or deliver their baby.

The alerts often include directions to take additional action — such as medical testing on the parent or baby, or to prevent the baby from leaving the hospital with the parent. It can lead to newborns being taken away from their parents for days, months or even years.

“They’re problematic in the sense that unfortunately they were most often deployed against Indigenous, racialized and disabled parents,” said lawyer Tina Yang with Waddell Phillips PC in Toronto. She is helping lead a proposed class-action lawsuit against several Ontario children’s aid societies and the province.

Ontario ended the controversial practice in 2020, while several other provinces and territories stopped between 2019 into late last year. Quebec is the only remaining province to practise birth alerts.

“It’s unconstitutional and illegal,” said Yang.

Often, birth alerts are issued without letting the pregnant person know and without evidence of real risk, according to Yang.

That’s why it’s hard to know exactly if someone was subjected to one, she said — and in some cases, one of the only ways to tell is to request records from these institutions.

It was just horrific.– Kathleen Rogers

Several years, even decades, have passed since Audrey Redman, Kathleen Rogers and Neecha Dupuis gave birth, and with proposed class-action lawsuits on birth alerts underway, they say they’re ready to seek records on what exactly happened to them and why.

“I don’t know why [Children’s Aid Society] had red-flagged me. I still don’t know to this day,” said Dupuis, whose son is now 11 years old.

“That’s something I just kind of lived with.”

Redman, Rogers and Dupuis — who have become friends living in Ottawa — are all survivors of the Sixties Scoop, when child welfare authorities took thousands of Indigenous children from their families and placed them with non-Indigenous foster or adoptive parents.

As some of them open up for the first time publicly about their own birthing stories, they say the systemic taking away of Indigenous children in Canada needs to stop with their generation.

“Hands off,” said Redman. “You’ve taken our children, you’ve taken our babies. Enough.”

“I want to make sure this stops so it doesn’t come after my children, my grandbabies,” said Rogers.

“It’s going to stop with us.”

Separated at birth for 3 months

Kathleen Rogers was feeding her son when social workers and security guards showed up to her hospital room at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre.

It was Dec. 20, 2010, just three days after he was born.

“They literally took my son off me while I was breastfeeding,” said Rogers. “Panic. I felt trapped. I felt cornered.”

Rogers had travelled down to Winnipeg alone to give birth, after going on maternity leave from her job as an educational assistant at a school at Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba.

“It was just horrific. And I didn’t know what to do,” she said.

WATCH | Rogers shares her story:

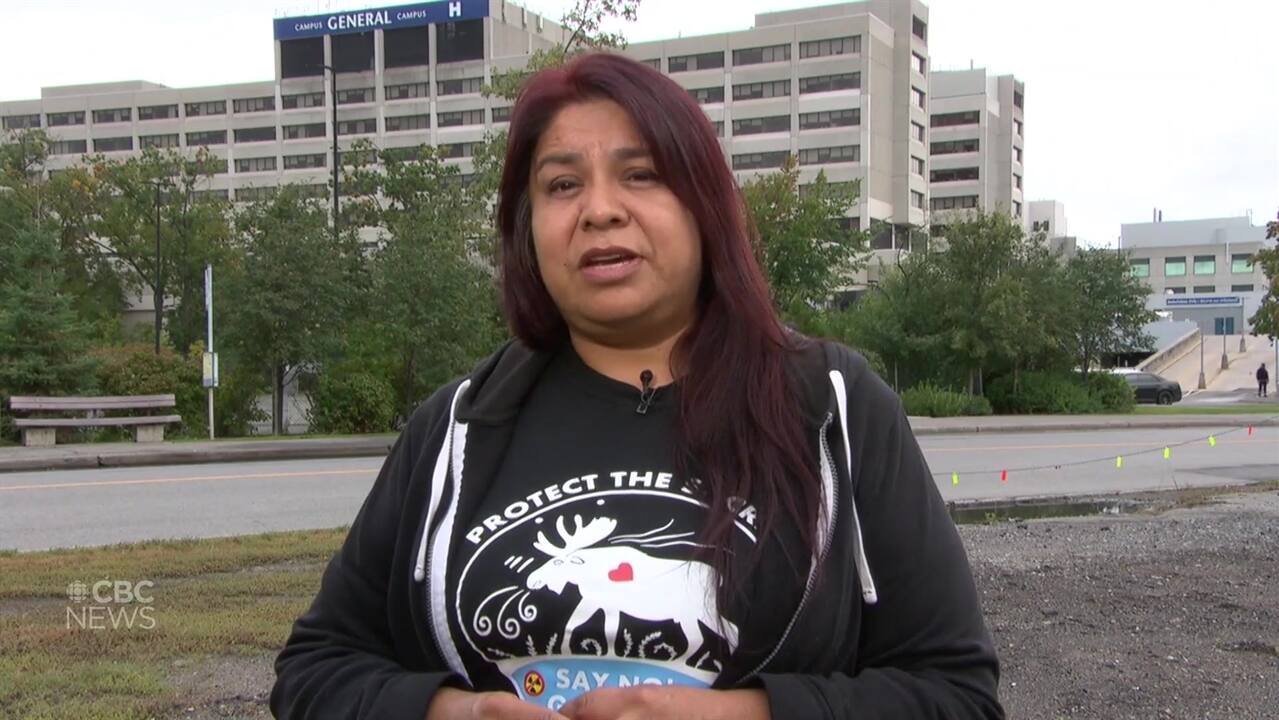

Kate Rogers says she still doesn’t know why child welfare agencies removed her newborn son from her care for three months after she gave birth in 2010.

Her baby was transferred from the care of Child and Family All Nations Coordinated Response Network (ANCR) to Kinosao Sipi Minisowin Agency (KSMA) — both Manitoba child welfare agencies.

A 2011 letter from KSMA to the province admitted the two agencies learned “Ms. Rogers posed no threat to the child,” and she was “well able to provide the necessary care” for her baby.

Rogers spent three months in court and regained custody of her son.

She calls herself “lucky” because she was able to hire a Winnipeg lawyer with the help of her adoptive brother.

Through her laywer, Rogers was able to understand a little more about why her son was taken, but she said many things remain unclear.

“Basically they thought I was this drunken Indian,” she said. “It was a wrongful apprehension and there was no proper explanation for this.”

Rogers and her son have since moved to Ottawa, but she said Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa have shown up at her door multiple times.

“I have a target on me and on my son,” she said, getting emotional. “And I’m tired of it.”

She plans on joining the class-action lawsuit for birth alerts and just began her journey to seek documents about her case. After initially inquiring, Rogers learned she has to make a formal request for records from the hospital.

“The whole thing was traumatic and it’s really scary because I built them up to be … this huge monster.”

Rogers, who plans to seek counselling before digging for more answers, said governments and institutions need to be held accountable.

“I’m just one of the many stories that this has happened to,” she said. “The truth needs to come out.”

Threats before son was born

Neecha Dupuis said she was five months into her high-risk pregnancy when a nurse at The Ottawa Hospital asked her if she drank or did drugs.

Prior to getting pregnant, she had taken medical cannabis for her degenerative disk disease. What she heard next changed the course of her pregnancy.

“She had told me, ‘You can lie to me all you want. We’re going to test your baby’s first urine and if we see there’s any marijuana … CAS will be standing at the door and they will take your baby.'”

Dupuis gave birth on July 23, 2011.

Moments after her C-section, she said her baby was taken away for jaundice testing — and for 10 minutes, she wondered if he was taken away for good.

“Time just stopped,” she recalled. “I didn’t know if I was ever going to see him again.”

Her baby was returned, but when Dupuis was set to be discharged, she was stopped.

“One of the nurses had come up to me and she says, ‘You can’t leave. Children’s Aid Society red-flagged you.'”

Dupuis called her advocate at Minwaashin Lodge Indigenous women’s support centre, and she believes they advocated for her to leave the hospital with her baby that day.

WATCH | Dupuis shares her story:

Neecha Dupuis, who was told she had been “red-flagged” by Children’s Aid Society when she tried to leave the hospital with her newborn, says her son would have missed out on important connections to his heritage if he had been apprehended.

Dupuis, a human rights and land defender, wrote to the hospital this summer to get records of what happened 11 years ago.

The Ottawa Hospital told her to pay a fee to formally request information.

“It’s just another blockade,” said Dupuis, who believes the fees should be waived for women who suspect they’ve had birth alerts issued on them.

“[My son didn’t] exist on this planet and they were already targeting him.”

Standing in front of The Ottawa Hospital, Dupuis lights up talking about her now 11-year-old son.

She boasts about Alex’s time at Ojibway Nation of Saugeen in northern Ontario reclaiming his culture, his advocacy work walking hundreds of kilometres against plans to dump nuclear waste near their territory, and his plans to build houses for northern communities.

“He’s learning of a world that he would never have known if he was taken,” said Dupuis.

Carrying trauma for 50 years

For more than 50 years, Audrey Redman has carried the trauma of losing her baby for 10 days after she gave birth while visiting British Columbia.

“Trauma doesn’t go away. Trauma is embedded in us. We carry it with us,” said the 71-year-old from Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation in Saskatchewan.

Redman gave birth to her son at Vernon Jubilee Hospital in Vernon, B.C., on Aug. 13, 1972.

But she was robbed of the joy of becoming a first-time mother before she could even hold him.

“They told us that they wouldn’t let him go until we had a home,” said Redman, who was travelling across North America during that time.

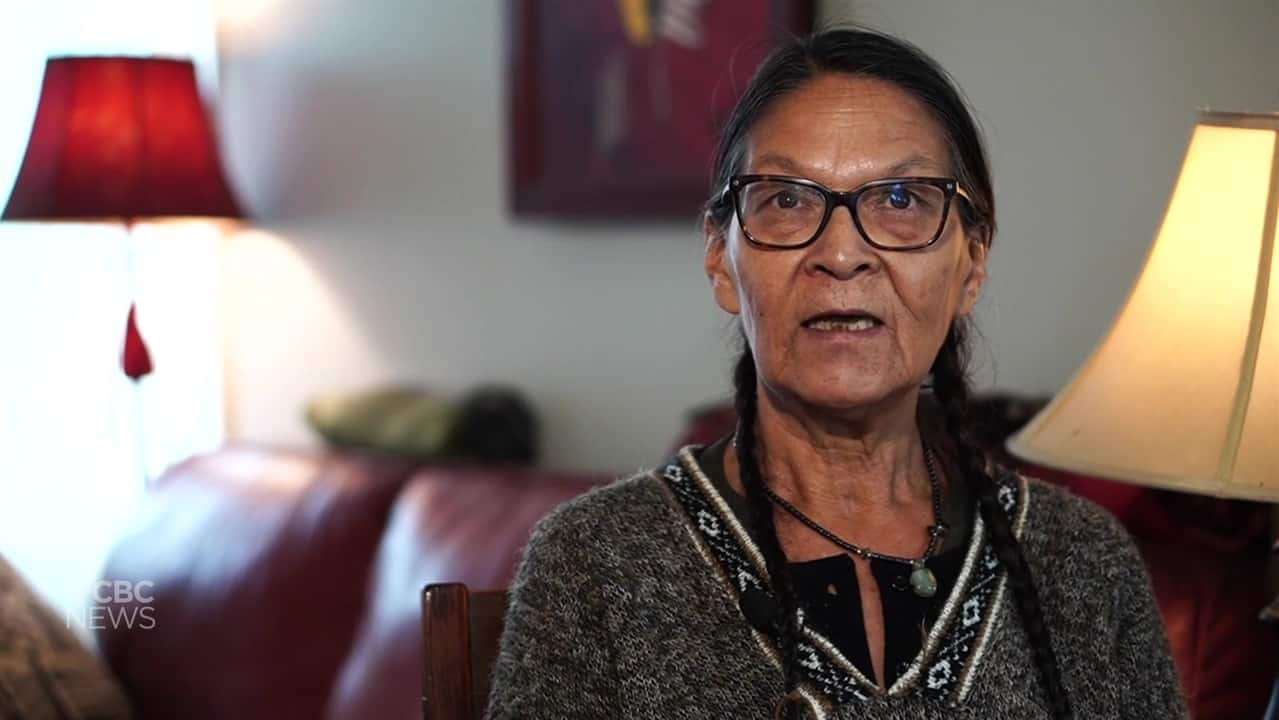

WATCH | Redman reads a poem she wrote about losing her son:

Audrey Redman says the trauma of having her son apprehended after his birth has followed both of them for the last 50 years.

For 10 days, Redman and the baby’s father frantically searched for a rental nearby, thousands of kilometres from Toronto where they were living before the trip, so they could get their son back.

She found a place and the family lived in B.C. for about two years before moving back to Ontario.

Looking back at her birthing journey, while sitting at her dining table in her Ottawa home, Redman wipes away tears as she explains how her son still struggles with separation anxiety.

“You don’t do that to a new mother,” said Redman, who’s also a residential school survivor. She chose to give birth to her four other children at home.

“That’s where I felt I was safe and my babies would be safe.”

When Redman thinks about obtaining documents about her situation, as she considers participating in the proposed class-action lawsuit, she feels it’s another way the system devalues and excludes Indigenous women.

“To expect us to go out and dig up documents out of their archives to prove what they did, I mean, that’s double injustice,” said Redman, a writer and journalist.

- Do you have a story to share? Email [email protected]

Obtaining records through Freedom of Information requests can take months or even years and could cost hundreds of dollars, depending on how many records are processed.

She said if Canada is committed to reconciliation, institutions should proactively provide them to women who’ve experienced birth alerts, for free.

“I don’t think we are the ones that ought to be doing that. They ought to be providing them.”

‘Completely unchecked system,’ says lawyer

Yang says birth alerts may remain an “ongoing concern,” as some women in Ontario are still coming forward alleging it’s happening to them.

It’s a “completely unchecked system,” adds Yang, because children’s aid societies were able to issue alerts without any oversight from the province.

Now, as her firm prepares to bring the lawsuit to get certified before the court, Yang encourages people to seek records if they have the time and means to.

Though, she admits, the process is not particularly accessible.

“It’s a layered injustice on top of the underlying injustice,” she said.

Flexibility can be built into the resolution for a class-action, especially for historical claims, she explained. This could include accommodations for those whose records are no longer available.

However, Yang warns it’s possible people could have suffered apprehensions of their newborns while not being subject to birth alerts — sometimes the apprehension can happen when health-care workers flag an expecting parent to child welfare agencies first, or if welfare authorities got involved early in a child’s life but did not act prior to their birth.

Requesting records is often the only way to prove someone’s been targeted by a birth alert.

CBC has requested information from the three hospitals where Redman, Dupuis and Rogers gave birth. The hospitals said they can’t comment due to patient privacy reasons, but said the women must personally request access to their health records.

A Shared Health Manitoba spokesperson said it considers waiving fees for patients on a case-by-case basis.

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools and those who are triggered by these reports. A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for residential school survivors and others affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419

Mental health counselling and crisis support is also available 24 hours a day, seven days a week through the Hope for Wellness hotline at 1-855-242-3310 or by online chat at www.hopeforwellness.ca.

Some other local resources:

For all the latest health News Click Here