2 years into the pandemic, Manitoba suffers Canada’s 2nd-highest COVID-19 death rate | CBC News

Gordon Dreilich loved to hunt and fish. He followed the Jets and Bombers. He played hockey when he was young, volunteered as a coach and worked as a professional carpenter.

The Winnipegger had liver and kidney disease before he contracted COVID-19 in late 2020. He ended up in hospital and lived weeks in intensive care but, according to his sister, never quite recovered.

Dreilich’s long-term effects included panic attacks and being unable to catch his breath. Four months after he got out of the hospital, he went back for a liver transplant and didn’t survive.

He died in June at age 63.

“He went right to the hospital, and that was it, we never saw him,” said his sister, Charlene Fewings.

She considers her brother a victim of COVID-19 even though she remains unsure whether his death is included in Manitoba’s official tally of fatalities attributed to the disease.

“I’m not ready to see the reports of what took place. It’s still very fresh,” she said.

“It affects everybody differently, and I think that’s the big thing. You don’t know how severe it’s going to be for you. And just one person’s death that could be preventable … is too many.”

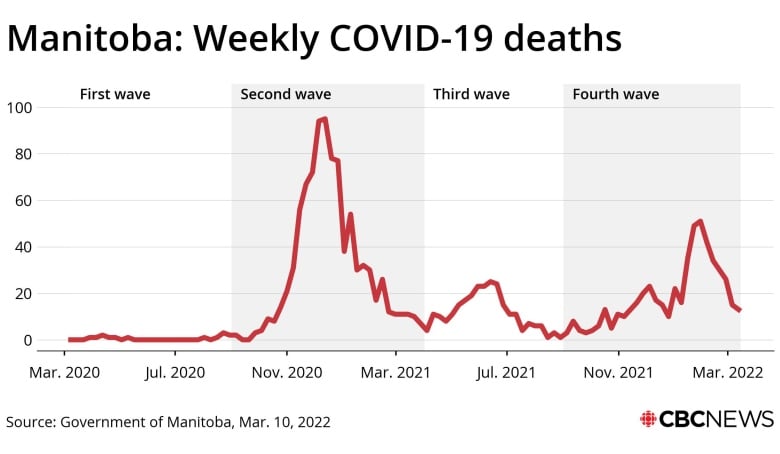

Two years ago, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Since then, no fewer than 1,710 Manitobans have died from the disease, according to the official provincial count.

That includes 667 in 2020 alone. Only cancer and heart disease caused more deaths in Manitoba that year, according to Manitoba Vital Statistics.

The province reported another 725 COVID deaths in 2021 as well as 318 this year so far.

In purely numerical terms, the death of 1,710 people over two years is comparable to the disappearance of the entire population of Roblin, Man.

In relative terms, the COVID death rate in this province is even more significant.

Combination of factors in high death rate

Two years into the pandemic, Manitoba continues to have the second-highest COVID-19 death rate in Canada: 123 COVID deaths for every 100,000 people, according to federal data.

Only Quebec has a higher death rate due to the disease, with 164 COVID deaths per 100,000 people over the course of the pandemic.

Manitoba Health Minister Audrey Gordon did not respond to requests for comment about Manitoba’s high COVID-19 death rate.

There is likely no single reason, says Souradet Shaw, a Winnipeg epidemiologist.

“Instead, it is likely that a combination of factors has contributed to what we are seeing overall,” he said.

Dr. Brent Roussin, Manitoba’s chief provincial public officer, attributed part of Manitoba’s high COVID-19 death toll to the outbreaks that swept through Winnipeg personal care homes during the fall and winter of 2020, when the second wave of the pandemic claimed the lives of hundreds of seniors.

The relatively poor health of Manitobans prior to the pandemic also played a role, Roussin said.

“Certainly one of the thoughts is the underlying health and the underlying determinants,” he said.

Those determinants, more formally known as the social determinants of health, include comparatively poor access to health services in rural and remote Manitoba communities, especially First Nations.

“The overall health of our population is tied to the health of our racialized communities, and especially our Indigenous population,” Shaw said.

“Unfortunately, in the case of Indigenous peoples in Manitoba, the legacies of colonialism and systemic racism are still being played out, and has acted to systematically create barriers to health and wellness.”

Other social determinants of health include substandard housing, given that the more people who live in a home, the more difficult it is to prevent COVID-19 transmission within households.

Another determinant is income, as those working lower-wage jobs — particularly in the service and food-processing industries — were less able to work from home when community transmission was high.

Another determinant is ethnicity itself, as newcomers to Canada and Indigenous people are more likely to make less money, live with more people and have worse access to health services.

“COVID-19 has served to amplify existing inequities,” Shaw said. “Those who are already subjected to higher rates of illness and death, period, have only had their risk for death and illness heightened due to COVID-19.”

Vaccination rates also play a role

Low vaccination rates in parts of Manitoba’s Southern Health region also appeared to drive up Manitoba’s COVID-19 death rate, Shaw said.

During the second wave in 2020, which took place before vaccines against the illness were available, the Winnipeg health region was over-represented among the ranks of the COVID dead. With 56 per cent of Manitoba’s population, Winnipeg accounted for 70 per cent of the province’s COVID-19 deaths.

Yet from mid-April 2021, when the third wave started, until the end of last year, the Southern health region stood out. With only 15 per cent of the provincial population, it accounted for roughly 33 per cent of Manitoba’s COVID deaths.

“The strongest factor here, I suspect, would be the lower proportion of people vaccinated in Southern Health,” Shaw said.

While the third wave hit Manitoba intensive care wards harder than any other wave, the Omicron wave early this year has proven deadlier. More people have died in this province during this most recent wave of the pandemic than at any other time since the second wave in 2020.

The main explanation is the massive number of infections from the Omicron variant, whose less severe fatality rate is countered by its more contagious nature.

Dr. Tara Moriarty, a Toronto infectious disease researcher, estimates there may have been 10 times more Omicron infections in Manitoba than official counts document.

She previously conducted research that suggests Manitoba undercounted its COVID-19 deaths in 2020, based on factors that include studies to determine the prevalence of COVID antibodies among the general population.

“It’s clear now that there were there was quite a high percentage of likely COVID deaths that were missed,” she said, adding she expects the undercount to continue through 2021.

To Charlene Fewings, it doesn’t matter whether her brother Gordon is ever included in the official count. She’s already convinced COVID-19 weakened him to the point where he did not survive.

“This is a disease that we can control, with vaccines and with common sense,” she said. “We shouldn’t be losing people to a virus.”

Two years ago, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Since then, no fewer than 1,710 Manitobans have died from the disease, according to the official provincial count. 2:22

For all the latest health News Click Here